Trauma Informed Collaboration

Trauma Informed Collaboration

We refer to the strong emotions that can unexpectedly affect our ability to maintain our steady state as trauma. Researchers continue to learn how our bodies can hold onto the memories of these traumatic events, even those that may have occurred very early in our childhood. Unfortunately, “few people go through life without encountering some kind of trauma” through no fault of their own. (1)

However, we can change how we interact with others to be more trauma informed. When we are willing to develop an awareness that the prevalence of trauma is significant and decide to operate with that knowledge and consideration, we can find more success in our interactions and collaborations with others.

This article will explore some of the fundamentals of trauma informed collaboration as a respectful, supportive approach that helps build resilience.

What is trauma?

Many people “mistake ordinary hardship or distress for genuine trauma”, which can lead to them start using the word, trauma, as they reflect on various life incidents and memories.(2) Not every difficult situation is categorically traumatic, and not all traumatic events will be debilitating. Most of the time, we can move beyond the initial feelings that these bad experiences stir in us. When these experiences don’t easily fade into memory, they could be viewed as causing longer-term harm.

For something to be classified as traumatic in the psychological sense of the definition, the experience is:

- Out of the person’s control

- Sudden and unexpected

- Harmful or life-threatening

- Damaging to a person’s sense of safety

- Responsible for creating overwhelming vulnerability (3)

Trauma affects the body’s sympathetic nervous system by creating a state where it perceives it is constantly at risk and should be ready to respond to threats at any moment. Living with this kind of hypervigilance means that the body’s usual fight, flight and freeze responses are always activated. The stress hormones and adrenaline our bodies produce continue to circulate rather than follow the expected path of clearing out of our systems when the crisis ends so that we can return to a more relaxed state.

Researchers like Dr. Bessel van der Kolk and Dr. Gabor Maté, who have studied and helped to classify the many different types of trauma, have shown that over time, unresolved or even unconscious trauma disturbs both physical and emotional functions. These disruptions can cause everything from pain and sleeping problems, to chronic illness and severe emotional disturbances that affect someone’s sense of who they are and their relationships.

It may be helpful to realize that trauma can: (4)

- Affect as a single event or repeated occurrences of events over time

- Arise from interpersonal relationships of people who know each other

- Influence developmental stages and patterns of emotional, social, and psychological growth

- Be political in nature, threatening people’s lives, beliefs, culture, and livelihoods

What is trauma informed collaboration?

Trauma informed collaboration is an approach you can adopt as a regular part of how you interact with people daily. It means that you acknowledge and are aware of and have an appreciation that inputs – even of the most seemingly innocuous nature – can create sensory overloads in people that are traumatic responses. When someone reacts unexpectedly, it can be challenging to understand why. Sometimes it can turn a situation into one that is unintentionally counterproductive and can damage our relationships and, potentially, even future interactions. By becoming trauma informed, we can influence the outcomes of our interactions so they have the potential to be more consistent, positive, and productive for everyone.

Is this what it means when we hear something is triggering for someone?

A trigger is an association someone makes that can inadvertently kick-off “re-traumatizing interactions” that cause them to experience a “dysregulated” or intense stress response. (5) Being triggered means someone is re-experiencing trauma. It isn’t just being “uncomfortable “or sensitive or feeling that something is “rubbing you the wrong way.” (6) A person may only be aware that something will necessarily act as a trigger for them once it happens.

Being more trauma informed, that is, aware of how far-reaching trauma can be, means that we can become more attuned to signals in people’s body language that indicate someone is displaying a traumatic stress reaction.

Here’s what you might notice: (7)

- A shift in someone’s posture where they appear more nervous, uneasy, or afraid by shifting their position frequently, withdrawing or even turning their body away from an interaction.

- Trembling fingers, clenching and unclenching of fists, fidgeting, or using something physical that is nearby to create a protective barrier (such as a bag, pillow or book).

- Self-soothing gestures such as putting a hand on their head, neck, or lap.

- Rapid and quick facial expressions such as

- oraised, lowered, or furrowed eyebrows

- ofrowning or lowering of lip corners, pursed lips, or lip biting.

- Reluctance to make eye contact, looking bored, off to the side, or off in the distance.

- Crossed arms and legs, tapping and jiggling feet.

- A higher-pitched tone of voice, more rapid speech than usual, or speaking slowly and quietly or with definitive emphasis on certain words.

Why is trauma informed collaboration important?

Operating with the knowledge that most people have experienced traumatic events is a supportive approach that actively demonstrates that you are caring and compassionate about your connections and relationships with others in your own life. It also is a way to influence interactions, experiences, and environments to make them healthier at home, in the community, or at work. You might help someone who is having trouble regulating their emotions or reduce the chance that they could display challenging behaviours.

Developing your trauma informed approach takes time. As you learn, conscious practice will help you to build better relationships. More and more healthcare professionals are adopting this approach as a standard of care because they realize the benefits. You may have heard it referred to as person-centred care. (8)

How does the prevalence of trauma affect people’s experiences of seemingly ordinary events?

It may be surprising to learn how significantly trauma affects nearly everyone.

- 70% of U.S. adults have experienced some traumatic event at least once in their lives (9)

- 75% of Canadians will experience at least one traumatic event in their lifetime (10)

- 1 in 10 people in Canada have been diagnosed with PTSD (11)

Often, people display symptoms of trauma in their interactions with others. These can present as: (12)

- Physical changes

- Headaches, heart rate increase, sweating

- Exhaustion, loss of appetite, loss of libido

- More susceptible to illness

- Constipation/diarrhea

- Hypersensitivity or hyperawareness (to sounds and/or touch)

- Harmful indulgences (alcohol, drugs, food)

- Emotional changes

- Fear, depression, anxiety, panic

- Extreme mood swings, rage, anger

- Withdrawal or isolation

- Guilt, blame, shame

- Loss of interest in regular activities

- Flashbacks or nightmares (PTSD)

- All of these emotional changes could stem from a PTSD diagnosis,however, some or few people go on to develop what we consider PTSD (13)

Why is it essential to adopt a trauma informed collaborative approach?

This approach aids our ability to respond to stressful situations in healthy ways. It might help to think about it using these five words: (14)

- Realize that stress and trauma happen to all of us.

- Recognize that our reactions are attempts to feel safe again.

- Respond with understanding, compassion, and patience every time.

- Resist re-traumatizing to boost emotional safety and avoid triggering events proactively.

- Resilience helps keep the focus on people’s strengths.

By adopting principles founded in safety, empowerment, trust, transparency, collaboration, supportive help, and attentiveness to historical and cultural issues, you’ll become more confident in yourself and those you are interacting with. Think about how this approach could be beneficial for equity deserving groups, such as the LGBTQ2S+ community, and actively work to address misogyny, racism, and marginalization.

Trauma informed collaboration helps you develop healthy and appropriate boundaries. It allows you to intentionally lead from a place of empathy in all your interactions. It’s a powerful tool that can alleviate or eliminate discrimination, promote understanding, and support harmony in co-existing despite our differences.

References:

1. Psychology Today Staff (n.d.). Trauma. Psychology Today. Retrieved, May 19, 2023 from https://www.psychologytoday.com/ca/basics/trauma

2. Ibid.

3. Ibid.

4. Homewood Health eLearning program: Trauma Informed Collaboration. (n.d). Developed and delivered by Crisis Management Clinical Managers.

5. Dubé, Kate, LCSW. (2021 July 22) Trauma Informed Care: What is it and Why is it Important? FOOTHOLD Technology: Mental Health. Retrieved May 19, 2023 from https://footholdtechnology.com/news/trauma-informe…

6. Cuncic, Arlin. (updated 2022 March 10). What Does It Mean to Be ‘Triggered’ – Types of Triggering Events and Coping Strategies. Very Well Mind.com. Retrieved May 19, 2023 from https://www.verywellmind.com/what-does-it-mean-to-…

7. Good Therapy (updated 2019 November 1). What Is Your Client’s Body Language Telling You? ˆ Good Therapy.org. Retrieved May 19, 2023 from https://www.goodtherapy.org/for-professionals/mark…

8. Homewood Health eLearning program: Trauma Informed Collaboration. (n.d). Developed and delivered by Crisis Management Clinical Managers.

9. The National Council for Behavioral Health (n.d.). How to Manage Trauma. The National Council.org. Retrieved May 19, 2023 from https://www.thenationalcouncil.org/wp-content/uplo…

10.Homewood Health eLearning program: Trauma Informed Collaboration. (n.d). Developed and delivered by Crisis Management Clinical Managers.

11. Ibid.

12. The National Council for Behavioral Health (n.d.). How to Manage Trauma. The National Council.org. Retrieved May 19, 2023 from https://www.thenationalcouncil.org/wp-content/uplo…

13. Homewood Health eLearning program: Trauma Informed Collaboration. (n.d). Developed and delivered by Crisis Management Clinical Managers.

14. Ibid.

Celebrating Pride Means Supporting 2SLGBTQ+ Mental Health

Celebrating Pride Means Supporting 2SLGBTQ+ Mental Health

June is a time for celebrating the diversity of Canada’s 2SLGBTQ+ communities. But it’s also a time to reflect on how we can nurture and support that diversity every day of the year.

The 2SLGBTQ+ community is disproportionately affected by mental health and addiction issues, and it prevents many of its members from living their best lives and reaching their full potential. For families, friends, and caregivers alike, changing the way we think about 2SLGBTQ mental health and addiction treatment and recovery can transform the outcomes.

Progress and challenges

There is much to celebrate during this year’s Pride Month. As of 2023, Canada is home to one million individuals who identify as 2SLGBTQ+, which represents 4% of the total population aged 15 and older. Three-quarters of Canadians support same-sex marriage, and 61% say they support LGBT people being open about their sexual orientation and gender identity with everyone. Just last year, the federal government unveiled a five-year, $100 million plan to support 2SLGBTQ+ communities across the country.

Yet in some ways, 2SLGBTQ+ visibility and acceptance have never felt more fragile as there is often backlash. Between 2019 and 2021, hate crimes based on sexual orientation rose nearly 60% to reach their highest level in five years.

More than ever, we need to make an effort to understand, celebrate, and make room for queer lives and identities, and that’s especially true when it comes to supporting 2SLGBTQ+ mental health and addiction treatment.

The cost of being queer

The cost of being queer

In a perfect world, people of all genders and sexual orientations would be given equal opportunities to thrive. But the reality is that 2SLGBTQ+ Canadians still face multiple barriers to health, wealth, and wellbeing.

Many 2SLGBTQ+ Canadians live with the trauma caused by secrecy, stigma, discrimination, and fear. In addition to being the target of hate crimes, they are also more likely to experience financial distress, homelessness, and housing insecurity than heterosexual Canadians. Canadians who are 2SLGBTQ+ also have fewer job opportunities and earn significantly less than straight, male counterparts and experience frequent microaggressions at work. A lack of access to medical care, suboptimal healthcare experiences, and poorer health outcomes also diminish quality of life for queer people.

A mental health crisis

In the face of so many challenges, it’s unsurprising that the queer community sees a higher proportion of mental health and addiction issues.

Courtney Sullivan, Addiction and Mental Health Therapist and Support Coordinator at Homewood Health Centre, which is located in Guelph, Ontario and one of the largest mental health and addiction facilities in Canada, provides both outpatient and inpatient treatment for addiction and mental health. They work with clients who identify as queer, including individuals who may be experiencing homelessness, job loss, trauma, addiction, and a range of mental health issues.

“There is a lot of stigma towards the queer community,” they explained. “A lot of people have their families disown them or kick them out or withhold family support. A lot of queer youth, in particular, end up in the shelter system, which exposes them to trauma and substance use, and their mental health can get a lot more complex.”

Research shows that 2SLGBTQIA+ Canadians are seven times more likely to abuse drugs or other substances and five times more likely to have mental health issues. Sexual-minority Canadians are also approximately 25% more likely to contemplate suicide (40% vs. 15% for the general population) or have a mood or anxiety disorder (41% vs. 16%).

Treatment challenges

Not only do 2SLGBTQ+ have a higher likelihood of developing mental health issues and addictions, but their treatment journey is complicated by systemic ignorance and discrimination in the healthcare system.

According to a 2019 survey, 59% of nonbinary people were misgendered daily and only 47% felt comfortable discussing non-binary health concerns with their primary care provider. One in three said their primary healthcare provider had no knowledge about trans/non-binary health needs, and one in four did not have access to in-person spaces specific for non-binary people.

“There’s a large amount of queer people who don’t actually disclose their queerness to their health care providers,” said Sullivan. “The medical system doesn’t have the greatest history,” they continued, pointing out that as recently as the 1970s, homosexuality was classified as a mental disorder.

“People who do disclose to their doctors are often put in a position where they have to educate them about how healthcare should be delivered, which puts a huge burden on the queer community.”

It’s even more complicated for people with an intersectional identity that combines queerness with another identity that puts them at a systemic disadvantage, such as being a person of colour or an Indigenous person.

“Recovery programs and agencies and organizations really need to show their support to the queer community and signal that they are seen, that their experiences are respected, and that the facility is open to work with you,” Sullivan said.

While Sullivan advocates for big changes in the healthcare system, including hiring for diversity and developing organization-wide policies that reflect diverse perspectives, they also believe that small things can make a big difference. As an example, they described a recent situation when they brought a suicidal trans client who didn’t feel healthy at home to the hospital. Asking for help took tremendous courage, but the client was deadnamed three times in a row during the intake process, which almost made them reject treatment. (Deadnaming occurs when someone calls a transgender or non-binary person by the name they used before they transitioned. While deadnaming may be unintentional, it can feel stressful and traumatic because it questions or invalidates a person’s gender identity.)

“The hospital is supposed to be a healthy space, and most healthcare workers are well-intentioned, but systemic homophobia and racism can come out through the policies and the way things work,” they said. “Something as simple as restructuring medical charts so that gender information and preferred pronouns are easily available at a glance can change the experience. Or have care providers identify their pronouns, which is kind of like offering an invitation for that person to give you theirs too.”

S upporting 2SLGBTQ+ mental health

upporting 2SLGBTQ+ mental health

If you are a friend, partner, or family member of a 2SLGBTQ+ person exploring treatment options or actively in treatment or recovery, you can play an integral role in supporting their mental health and resilience.

For Sullivan, these communication tips can help to ensure they feel heard, seen, and supported throughout the journey.

Let them lead. “Your loved one might have a substance use issue, but if they’re not ready to hear it, don’t force it on them,” said Sullivan. “When people get scared, they make threats, like, ‘You need to get sober or else!’ But that ruins the opportunity and the trust.” Instead, let that person decide what they need and set the pace for treatment and recovery.

Keep an open mind. “Come at things with empathy and compassion. Listen to that person. Try to understand why they’re making the choices that they do.” Sullivan pointed out that for some members of the 2SLGBTQ+ community, the use of stimulants is an important part of their lifestyle and sexuality. “It all comes back down to the impact that the person’s substance use has on their life, and what that person identifies as being problematic.”

Respect their experience. “The trauma and the experiences that queer people have are different,” Sullivan explained. “Even if you’re cisgender and you get kicked out of your home, it’s still a different experience than someone being kicked out of their house because of who they are.” Respecting those differences can go a long way toward creating a space for authenticity and healing.

Pride in mental health

Pride in mental health

Pride Month is a time to celebrate the queer community and bring attention to the challenges it continues to face. The elevated risk of mental health and addiction issues is an important part of the story, and one that Homewood Health Centre and other mental health and addiction facilities in Canada are highlighting this year. We all have a role to play in supporting and protecting the mental health of 2SLGBTQ+ individuals, and that role goes beyond raising the rainbow flag.

“We’re having a flag-raising ceremony in honour of Pride here at Homewood, but that’s just the first step,” said Sullivan. “It’s about creating intersectional representation. You want people of colour working in your organization, you want Indigenous perspectives, you want queer perspectives. Be willing to hear the experiences of the people you employ and the people you support. Find out what it is that they’re looking for.”

Learn more about LGBTQ+ mental health.

Learn how to support children who identify as LGBTQ2+.

How to be an Ally

How to be an Ally

Being an ally is about far more than making a declaration. It’s a conscious, educated decision that leads someone to develop sincerity, focus on introspection, and learn about consistency.

True allies show solidarity for people whose circumstances are different and challenging. There should never be any expectation of recognition or gratitude. An ally must understand this and embrace it. Embracing allyship helps you realize how you live your life and can support earnest changes in behaviours in yourself and society that can contribute to shifts that chip away at injustices and inequities.

In this article, we will explore some of the fundamentals, clarifying what it means to make the personal decision to be an ally and why allies are necessary. We’ll also look at the actions allies can take to strengthen our workplaces and communities.

What is an ally?

An ally is someone who wants to partner with marginalized people in our society to help overturn oppression and inequities that center around topics such as race, cultural identity, gender, religion, sexual orientation, ability, and body type/appearance. Allies focus on standing up “for equal and fair treatment of people different from them” whose voices are underrepresented.[1]

Allies recognize that introducing consistency in their lives can result in solidarity with others because they approach things earnestly, knowing that the right kind of support can change behaviours and ideas. Allyship is most effective when it happens in the context of genuine relationships and everyday interactions.

A large component of being a successful ally is practicing self-awareness and self-accountability.

- An ally must acknowledge how their privilege has benefited them.

- They must be open to listening to understand and learn about the kinds of meaningful actions they can offer as a show of support for people lacking privileged advantages.

Another way to look at it is that an ally cares enough to make a conscious decision to support someone who is a member of a group that the ally is not a part of and who is having a negative experience in their life. They also recognize that allyship is not pity. When enough people decide to be allies, that’s the point where social and societal change begins to happen.

Allyship is only valuable if it’s consistent. It can also be contradictory if the ally enters a situation from a solutions-oriented perspective because they believe they know exactly how to fix a problem. The responsibility for learning about the challenges marginalized groups experience is not something for an ally to expect their marginalized contacts to offer. It’s up to the ally to seek accurate knowledge responsibly. An ally must self-educate consistently and without expecting recognition for their involvement.

Why are allies necessary?

We often adapt what we think, say, and do to blend in with the crowd. It can help us feel accepted, safe, and that we belong, leading us to behave in specific ways, like others in the group, so that we aren’t asked to leave it. Psychologist Robert Cialdini observed that “people copy the actions of others to know how to act in a certain situation. This idea stems from the assumption that if other people are doing something, it must be the correct thing to do.”[2] What’s interesting is that we tend to conform even when we observe or experience something that we know is wrong. The people around us subtly influence us: social actions and opinions are contagious, both good and bad.

Allies dare to reflect and recognize their privilege and use it to “influence inclusion and call out or challenge behaviour [that perpetuates] bias and systematic oppression based on race, gender, sexual orientation and ability.”[3]

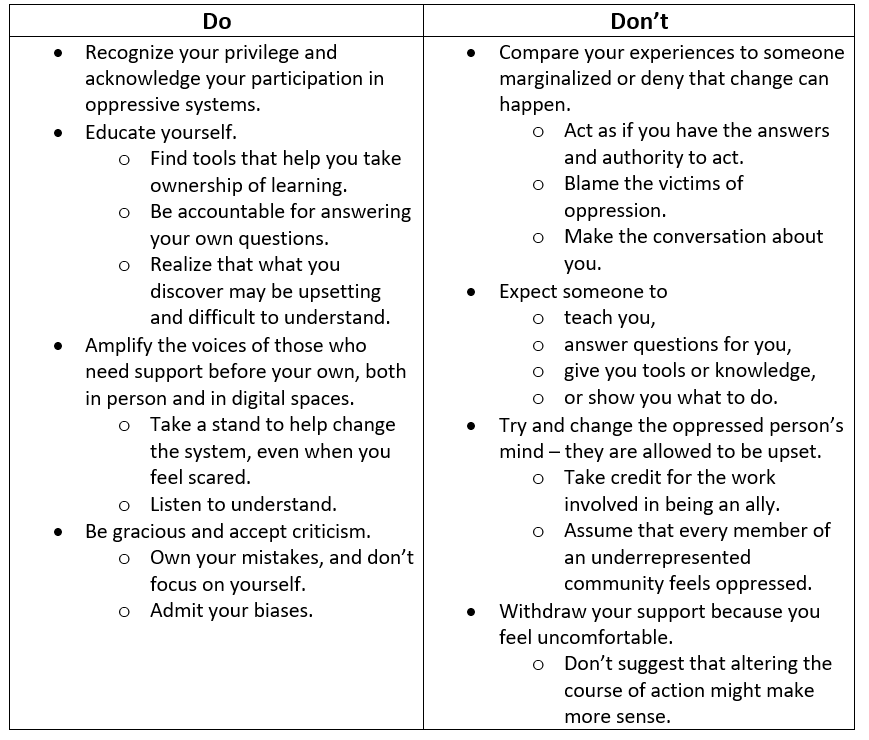

What actions can you take to become an ally?

Being an ally comes with great responsibility. Here are some considerations:

How can you be a better ally in the community?

Being present as an ally is about consistency. Show up for all people and groups, observing that each may take a unique approach. An example of a simple action you can take is to acknowledge important holidays and milestones.

Recognize that you might be the one who needs to change or stand up for change to correct a misperception. Pay close attention to language and ideas to reflect that in conversations to show you care. Stand up to discrimination when you see it by modelling active listening. For example, take time to learn the correct pronunciation of people’s names. You could also support someone’s expertise and skills and invite them to share their knowledge within the community.

You also need to respect boundaries. Some people may adapt their behaviours for safety reasons. Don’t chastise them for doing that. Follow their lead and try to understand why they are making that choice. Think about what a shift in behaviour in the future could do that might result in a safer experience for them.

How can you be a better ally at work?

You can start by recognizing that there are inequities in the workplace that affect people’s physical and mental health significantly. These might be centred around income and lifestyle or other factors that affect the identity they portray at work and their ability to be their authentic self.

Known issues include:

- Unequal pay

- Lack of diversity

- Underrepresentation of people in marginalized groups in management/leadership positions

Remote work adds another complication. It’s easy for people to make assumptions about one another when their interactions are virtual. The lack of physical presence can introduce microaggressions that often have remote workers feeling excluded and undervalued.

Allies can help push for changes by actively advocating and participating in these approaches to ensure that concerns are discussed and not diminished.

Create space for productive discussions

Be willing to have and support uncomfortable talks, even if the topics are controversial. It holds the organization accountable for addressing Diversity Equity and Inclusion (DEI) issues, especially if HR policies are already in place.

Develop mentorship opportunities

Supporting allyship can be strategic, allowing people to become “collaborators, accomplices, and co-conspirators who fight injustice and promote equity” through the relationships that develop and actions taken during mentoring.[4] It can be the catalyst to drive change.[5]

Use a strategic and measurement-based approach

Engage in ongoing measurement to evaluate if your DEI policies are effective. This includes creating annual or quarterly plans that outline DEI initiatives that drive or align with the organization’s strategic plans; defining who is accountable for the initiatives, establishing and analyzing key performance metrics to assess the impact of initiatives and programs and incorporating on-going feedback from leaders and employees.

Change the usual ways feedback about DEI issues is collected

Allies can encourage people to share what the organization should start doing, stop doing, and stay doing. Keeping things simple can help everyone feel safe sharing their realities and bringing transparency to what is happening at work. People never want to feel like they are the only ones sharing their situations. There should be zero tolerance for inequity and discrimination.

References:

[1] Wells A. & White B. (2021 February 4) Why is Allyship Important? National Institutes of Health (NIH). Retrieved April 27, 2023 from https://www.edi.nih.gov/blog/communities/why-allyship-important

[2] Cherry, K. (2022 January 20, Updated 2023 March 5). Confirmity: Why Do People Confirm? Explore Psychology. Retrieved April 27, 2023 from https://www.explorepsychology.com/conformity/

[3] Rice, D. (2021 August 18). The Keys to Allyship: Understanding What an Ally Is and the Role They Play in an Inclusive Workplace. Diverity Inc. Powered by FAIR360. Retrieves April 27, 2023 from https://www.fair360.com/the-keys-to-allyship-understanding-what-an-ally-is-and-the-role-they-play-in-an-inclusive-workplace/#:~:text=In%20majority%2Dwhite%20societies%2C%20effective,privilege%20to%20drive%20tangible%20change.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

The Intersection of Sexual Identity and Mental Health

The Intersection of Sexual Identity and Mental Health

If someone were to ask you who you are, how would you answer that question? We would likely share the things that we instinctually feel form our identity and are essential for us to express. However, we would also likely assess the environment and situation we find ourselves in first to determine the degree of information to share. We gauge other people’s potential interests, determine if we are meeting them for the first time, whether alone or in a group, and collect details about the setting, their appearance, tone of voice, and facial expressions that give us clues. What we say is selective and doesn’t necessarily share every profound aspect of our life experience that has contributed to forming our identities to date at that moment, but rather those that are most important to convey a picture for them to receive and develop quickly to understand.

We can consider all the people, situations, and circumstances that help us determine our identities are like the spokes of a wheel. Ultimately, they converge and intersect at a central point of strength that holds them all in place, the hub. That is our essence, our sense of self: our identity.

In this article, we will look at how intersectionality is an approach to use in many aspects of our lives to develop a greater understanding of sexual identity and mental health, especially in the context of how different points of intersection affect the experiences of marginalized groups within our society. Opening our points of view can help us learn more about ourselves and other people and enhance our understanding so that we can all strive to live well and feel better.

What is intersectionality?

Intersectionality is a way to look at all the different aspects of someone’s life that have influenced them and their experiences. For example, considering where they grew up, where they live now, what their childhood was like, how they were affected by their families and culture, and whether they have had economic advantages that have increased their social standing would all factor into creating both inequalities and power.[1] However, some influences can be even more critical in developing someone’s social standing where “divisions such as gender, ethnicity, class and lifecourse positioning” are likely to shape more people’s lives than others.[2] Researchers have discovered that the social divisions experienced have a more lasting role in influencing a person’s life.[3] Intersectionality as an approach examines how multiple “forms of discrimination…and oppression, like racism, sexism, and ageism might [also] be present and active at the same time in a person’s life.”[4]

The importance of taking an intersectional approach to sexual identity and mental health

Studies are starting to explore how important it is to view intersectional aspects of our identities through a multi-factor lens. Evidence shows how various health conditions are treated socially and by healthcare providers and systems. Overall, there needs to be a focus on reducing the “burden of stigma.”[5]

The intersection of sexual identity and mental health tremendously influences someone’s sense of belonging and identity. But it’s also important to understand that looking at points of intersection should not be limited to comparing only two tangents because it’s the “convergence of multiple systems of oppression that together underlie the ways the ways that individuals interact with the world around them and how they are treated by others.”[6] For those in the LGBTQ2S+ community, where there is a continuum of many sexual identities and genders, in addition to “diverse racial and ethnic groups, differing abilities, and a range of socioeconomic backgrounds” it is vital to acknowledge that divisions and negative connotations present in society make it exceptionally difficult for members to navigate their lives confidently and safely, especially when it comes to obtaining high quality, purposeful healthcare.[7] Negative health outcomes are compounded for LGBTQ2S+ individuals experiencing other forms of discrimination, including racism, colonialism, and ableism. Practitioners may be unaware of how unconsciously managing a case, instead of approaching a situation from a person-centric point of view, can create trauma for someone seeking medical care.

What do we know about mental health in LGBTQ2S+ communities?

Research shows that people in LGBTQ2S+ populations are affected by discrimination, marginalization, and harassment and, therefore, “often experience greater frequency of mental health problems as a result.”[8]

They are:

- more likely to experience depression, anxiety, suicidality, and substance abuse

- at double the risk of developing post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

LGBTQ2S+ Youth:

- experience risk of suicide and substance abuse at levels 14 times higher than their heterosexual peers

- 77% of trans respondents in one survey had seriously considered suicide

- 45% had already tried to end their lives

- trans youth and those who had experienced physical or sexual assault were at greater risk

Statistics also showed that:

- bisexual and trans people are over-represented among low-income Canadians

- trans people reported high levels of violence, harassment and discrimination when seeking stable housing, employment, health, or social services[9]

How does sexual identity interact with other social identities to shape bias?

One of the most significant challenges LGBTQ2S+ communities face is that, historically, the full spectrum of sexual identity has been associated with mental illnesses. The American Psychological Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Illnesses (the DSM-5) is the guidebook many professionals use to diagnose mental health disorders. However, “until 2013, being transgender was still considered a mental illness, and being gay or lesbian was considered a mental illness until 1973.”[10] Biased views and opinions about sexual identity are embedded and endemic in the fabric of the healthcare systems and governments.

The reality that many people face in terms of stigma is that living their authentic identities, which happen to be on a different position from heterosexism in a broad spectrum of sexual identities, often results in them being[11]:

- rejected by their families

- rejected by society

- vulnerable to violent acts

- forced to live with daily microaggressions in their homes and workplaces

- self-critical and experiencing negative emotions such as shame and guilt

- isolated

- chronically stressed

- anxious

Why do LGBTQ2S+ communities experience health disparities?

People whose sexual identity is on the LGBTQ2S+ spectrum face disparities in obtaining unbiased healthcare regularly. These can be related to harassment, where people are subjected to microaggressions, trauma, or violence. They can also face racial discrimination or even rejection from their families and society for what is sometimes perceived as a lifestyle choice. Finally, they can be affected by structural inequalities, including facing barriers to accessing mental health care and receiving a lower quality of care when treated.

Mental health risks for LGBTQ2S+ communities

People experience trauma, sometimes called “minority stress,” when they must repeatedly deal with discrimination and stigmatization to live their lives.[12]

For example, they might:

- Have to “come out of the closet” on multiple occasions, or sometimes daily

- Feel they need to “go back into the closet” to receive some care such as eldercare, long-term residential care, or palliative care

- Have their sexual orientation or gender identity revealed against their will in social settings or to their families

- Need to assess a situation carefully to determine if it is safe to disclose their authentic sexual identity

Minority stress is directly linked to psychological distress and higher suicide risk amongst LGBTQ2S+ communities. It can also contribute to the earlier onset of chronic diseases.[13]

Simply hearing repeatedly about hate crimes, violence, and anti-LGBTQ2S+ legislation can affect health and self-esteem, leading to depression or anxiety.[14]

As a result, people who identify as LGBTQ2S+ have an increased chance of developing more severe substance use and addiction complications because of increased frequency of mental distress, depression, self-harm, eating disorders, suicide, and IV drug use.[15]

How community supports and peer groups can help

People need to feel included in society and their communities, be free from discrimination and violence, and have access to economic resources to help them maintain positive mental health and well-being.[16] However, change and support also come from looking at intersecting factors as part of a more comprehensive approach to mental health treatment. Doing so can “help identify service gaps and prevent or reduce further harm.” [17]

We all have a role in challenging heterosexism, transphobia, and systemic forms of oppression. These are keys to improving mental health outcomes within LGBTQ2S+ communities.

- It can start with developing a better approach to sex education that is age appropriate and includes teaching about sexual diversity, gender identity, sexual health and diseases, and mental health, and addresses intersectionality as part of the standard school curriculum.

- Gay-straight alliance groups help build inclusion and save lives, especially for people who do not have support from families or schools.[18]

- Having safe places to meet, build community and reduce social isolation by supporting healthy connections is essential.[19]

What can people do to improve their mental health?

Improving your mental health can start with small, simple changes:[20]

- Connect with others who can relate to your circumstances, will accept you and provide emotional support

- Unplug from news and social media to reduce stress and fatigue that can lead to feeling hopeless, worried and fearing for personal health and safety

- Prioritize your physical health with good nutrition, restful sleep, and regular exercise. These will also help boost your mood and increase your energy

- Pursue creativity to express your feelings. It can help increase focus, ground you in the present and help you feel proud and accomplished

- Set boundaries so you are not faced with situations that compromise your physical or mental health. You don’t need to respond, and leaving an upsetting situation is okay

- Talk to professionals who can connect you with resources and supports to help you manage your emotions and mental health

Mental health resources for LGBTQ2S+ communities

We’ve compiled some resources that can help. Feel free to explore them while focusing on living well and feeling better.

Canadian

- itgetsbettercanada.org

- The Canadian Centre for Gender + Sexual Diversity | ccgsd-ccdgs.org

- Egale Canada | egale.ca

- Government of Canada: The human rights of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, 2-spirit and intersex persons

U.S.

- The Trevor Project | thetrevorproject.org

- The National Queer & Trans Therapists of Colour Network |nqttcn.com

- Human Rights Campaign: Tools for equality and inclusion. | hrc.org/resources

References:

1. Hopkins, P. (2018). Feminist geographies and intersectionality. Newcastle University. Retrieved March 24, 2023 from https://eprints.ncl.ac.uk/file_store/production/246036/DAEDDA02-4DB2-4B18-9120-7515E81E915F.pdf

2. Yuval-Davis (2011), as cited in Hopkins, P. (2018). Feminist geographies and intersectionality. Newcastle University. Retrieved March 24, 2023 from https://eprints.ncl.ac.uk/file_store/production/246036/DAEDDA02-4DB2-4B18-9120-7515E81E915F.pdf

3. Hopkins, P. (2018). Feminist geographies and intersectionality. Newcastle University. Retrieved March 24, 2023 from https://eprints.ncl.ac.uk/file_store/production/246036/DAEDDA02-4DB2-4B18-9120-7515E81E915F.pdf

4. Hopkins, P. (2018) What is Intersectionality? (00:11-00:22) Vimeo. Retrieved March 24, 2023 from https://vimeo.com/user83638171

5. Turan et al. (2019). Challenges and opportunities in examining and addressing intersectional stigma and health. BMC Medicine. Retrieved March 24, 2023 from https://bmcmedicine.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12916-018-1246-9

6. Yale School of Public Health (2022) Yale LGBTQ Mental Health Initiative: Intersectionality. Yale School of Medicine. Retrieved March 24, 2023 from https://medicine.yale.edu/lgbtqmentalhealth/projects/intersectionality/

7. Ibid.

8. Massie, M. (2020) A Facilitators Guide: Intersectional Approaches to Mental Health Education. UBC Workplace Health Services and Health, Wellbeing and Benefits). Retrieved March 24, 2023 from https://wellbeing.ubc.ca/sites/wellbeing.ubc.ca/files/u9/Facilitator%20Guide%20-%20Intersectionality%20and%20Mental%20Health.pdf

9. CMHA (n.d) Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans & Queer identified People and Mental Health. Canadian Mental Health Association. Retrieved March 24, 2023 from https://ontario.cmha.ca/documents/lesbian-gay-bisexual-trans-queer-identified-people-and-mental-health/

10. Massie, M. (2020) A Facilitators Guide: Intersectional Approaches to Mental Health Education. UBC Workplace Health Services and Health, Wellbeing and Benefits). Retrieved March 24, 2023 from https://wellbeing.ubc.ca/sites/wellbeing.ubc.ca/files/u9/Facilitator%20Guide%20-%20Intersectionality%20and%20Mental%20Health.pdf

11. Ibid.

12. Standing Committee on Health (Bill Casey, Chair) (2019). The Health of LGBTQIA2 Communities in Canada. House of Commons, Parliament of Canada. Retrieved March 24, 2023 from https://www.ourcommons.ca/Content/Committee/421/HESA/Reports/RP10574595/hesarp28/hesarp28-e.pdf

13. Ibid.

14. Collins, D. (2022). 6 Ways to Protect Your Mental Health as an LGBTQ+ Individual. One Medical. Retrieved March 24, 2023 from https://www.onemedical.com/blog/healthy-living/6-ways-protect-your-mental-health-lgbtq-individual/

15. National Institute on Drug Abuse (n.d). Substance Use and SUDs in LGBTQ* Populations. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; National Institutes of Health; National Institute on Drug Abuse; USA.gov. Retrieved on March 24, 2023 from https://nida.nih.gov/research-topics/substance-use-suds-in-lgbtq-populations

16. Ibid.

17. Ibid.

18. Standing Committee on Health (Bill Casey, Chair) (2019). The Health of LGBTQIA2 Communities in Canada. House of Commons, Parliament of Canada. Retrieved March 24, 2023 from https://www.ourcommons.ca/Content/Committee/421/HESA/Reports/RP10574595/hesarp28/hesarp28-e.pdf

19. Ibid.

20. Collins, D. (2022). 6 Ways to Protect Your Mental Health as an LGBTQ+ Individual. One Medical. Retrieved March 24, 2023 from https://www.onemedical.com/blog/healthy-living/6-ways-protect-your-mental-health-lgbtq-individual/

3 Ways Families can Support People in Addiction Recovery

3 Ways Families can Support People in Addiction Recovery

“While most of us have experienced some pain and anguish in our family, that family system can be a source of strength in healing from that pain.”

Dr. Julie Burbidge

Clinical Director, Homewood Ravensview

The negative impacts of addiction on families is well known. Less well known is the positive impact families can have on the addiction recovery journey. Parents, grandparents, spouses, siblings, and even children can play a powerful role in supporting a family member in addiction recovery and beyond.

In this blog post, we look at the difference families can make in the recovery journey and what they can do to support their loved ones as they transition from an inpatient treatment program to daily life.

Family support has a measurable impact

Supportive family dynamics can have a transformative impact. Family support can uplift every aspect of an individual’s life, from emotional wellbeing to physical health to academic and career success.

Even for an issue as complex and uncompromising as addiction, family support can make a measurable difference.

- A study of nearly 1,200 women who underwent inpatient treatment for substance abuse found that those with supportive families were less likely to relapse within six months of their discharge.

- A study of adolescents undergoing substance use treatment found that those who perceived their parents to be highly supportive had better outcomes than those who did not.

- A meta-analysis of 16 research studies found addiction treatments that involve family are associated with a 6% reduction in substance use compared to individual therapies.

- 65% of Canadians in treatment for an addiction said marital, family, or other relationships were the most important factor in initiating recovery.

Supporting a family member on the path to sobriety is no easy task, but the research is clear: family support can make a big difference.

“Positive attitudes and reinforcement from family members can inspire clients’ commitment to recovery,” explained Dr. Julie Burbidge, the Clinical Director at Homewood Ravensview, a private inpatient facility for mental health and addiction recovery in British Columbia. “It can also help them adapt to new challenges or limitations as they reintegrate with the wider world after spending time in treatment.”

Discharge is not the destination

When an individual completes a treatment program, it’s a major milestone and a cause for celebration, but it’s not the end of the road.

After the individual is discharged, the journey continues as they learn to resume their daily lives while remaining sober. The transition can be overwhelming, and it’s a time when family support in addiction recovery may be most needed.

While this transitional period is critical, it can be overlooked and under-resourced, which is why Homewood Clinics developed a series of post-discharge supports for patients and their families. Individuals who complete treatment are invited to participate in 12-month virtual support groups that meet weekly to focus on recovery management. For their families, an optional virtual meeting with a clinician is held each month at Homewood Ravensview. The facility is also launching a self-serve video hub where over 70 minutes of educational content covers a range of topics including talking to children about treatment, setting healthy boundaries, and understanding the stages of change in the journey to recovery. This will replace the virtual monthly meetings, and is meant to allow for more flexibility on when and how families receive these resources.

“Transitions are difficult because they involve uncertainty,” said Dr. Burbidge. “The more time and effort you put into planning for and discussing the transition plan, the more effective it will be.”

How to show your support

Supporting the recovery of an individual with an addiction isn’t easy, even for experts with years of specialized experience and training. For family members who don’t have that advantage, it’s even more intimidating.

Emotional dimensions can create further challenges. Even in families unaffected by addiction, relationships can be complicated. When addiction and mental health issues are added to the mix, the dynamics can be even more volatile.

“Being prepared for the transition home of a family member involves understanding your role in the recovery process,” said Dr. Burbidge. “It also means accepting that family life after treatment will be different and making a commitment to rebuilding relationships.”

Educating yourself ahead of time can help you prepare to provide family support in addiction recovery. Here are three of the most beneficial strategies for showing up in meaningful and constructive ways.

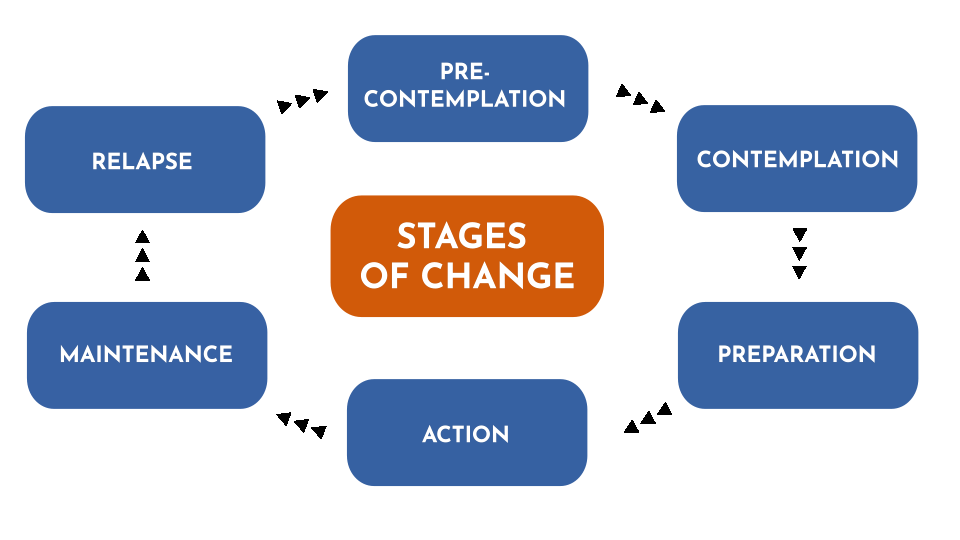

Understand the dynamics of change

People who undergo treatment for addiction are asked to change in profound ways, and that cycle of change doesn’t stop when they are discharged.

“Sometimes family members have the misperception that their loved one will be ‘fixed’ or ‘healed’ when they leave treatment,” Dr. Burbidge explained. “Treatment is an important step in a person’s healing and recovery, but the process continues long after their discharge.”

Understanding the stages of change can help family members recognize, accept, and meet people where they are in the journey.

The most important thing to understand about the path to change is that it isn’t tidy and linear. Just as a person with diabetes or asthma can relapse after being released from treatment, a person in addiction recovery may experience a relapse as they work toward sustained change. A relapse shouldn’t be seen as a failure but as one stage among many in the recovery process.

Stages of Change

As people pursue their recovery, they cycle through various stages that can involve new thoughts, attitudes, and behaviours. Every journey is different, and few journeys are perfectly linear. This diagram represents the change model used by Homewood Ravensview, a private inpatient facility for mental health and addiction recovery in British Columbia.

There are several ways you can help to prevent or mitigate the impact of a relapse:

- Talk to the person in recovery about relapse so they know you understand it’s something that might happen.

- Let them know that you are there to support them and ask if they would like you to play a role in their relapse prevention plan.

- Pay attention to your own behaviours. Families can sometimes fall back into old, destructive patterns.

Learn to communicate effectively

Effective communication is the key to healthy interpersonal relationships, but it’s easy to slide into defensiveness and blame during times of stress and anxiety.

Dr. Burbidge advises family members to try using a form of assertive communication called “‘I’ statements” to create a connection with the person they’re speaking to and avoid slipping into harmful communication patterns that rely on accusing, blaming, and shaming. ‘I’ statements focus on your own experience and how you feel about it rather than focusing on what you think the other person is doing wrong.

“This gives us a way to express our feelings in a manner that is respectful and increases the likelihood that the other person will be open to hearing what we have to say,” said Dr. Burbidge.

You can express yourself with ‘I’ statements using a simple formula: “I feel [describe your feeling] when you [describe the person’s actions] because [describe the reason it makes you feel a certain way].

Here’s an example:

| Conventional ‘you’ statement | ‘I’ statement |

|

“You never listen to me. You make me so angry because you just don’t care enough about me to bother to listen when I’m trying to talk.”

|

“I feel angry when you interrupt me because It’s important to me that I’m able to share my ideas with you and feel heard by you.”

|

Set and respect boundaries

During treatment for addiction, people learn how to create boundaries as a way of staying on the path toward healing. As the family member of a person in recovery, you can support them by recognizing and respecting those boundaries. Setting boundaries of your own can also be very helpful in allowing you to preserve your energies and self-respect as you explore new ways of relating to that person.

“Boundaries are a way to establish where you end and other people or external influences begin,” explained Dr. Burbidge. “They are a way of setting healthy limits around what we will and won’t accept or do in our relationships with others.”

To set a healthy boundary with someone:

- Describe the boundary you are setting or the action that is causing you discomfort.

- Express how the situation makes you feel using ‘I’ statements.

- Describe the behavioural change you are looking for in the future.

- Without making threats, describe the action you will take if your boundary is crossed.

Here is an example:

“I feel angry when you interrupt me because It’s important to me that I’m able to share my ideas with you and feel heard by you. Moving forward, I would like it if we could each take turns speaking. This will help us better understand each other and hopefully feel more connected. The next time you interrupt me, I will leave the room and we can continue the conversation later.”

Take the next step together

An individual who has completed an inpatient addiction treatment program has done some hard and courageous work toward furthering their recovery. Re-entering their normal lives post-treatment is the next big step in their journey. By understanding the stages of that journey and learning new ways of communicating and interacting along the way, families can make a positive difference in the individual’s recovery experience and outcomes.

“To truly understand the individual, we have to understand the family system of that individual,” Dr. Burbidge said. “While most of us have experienced some pain and anguish in our family, that family system can be a source of strength in healing from that pain.”

For more insight into supporting a family member in addiction recovery, read these articles from Homewood Ravensview, an addiction treatment program in British Columbia, Canada.

Understanding Family Dynamics: What healthy family traits look like, and how to identify toxic family dynamics.

Supporting Those with Addiction: How to support family members who haven’t reached out for help yet.

Top 5 Tips to Motivate Someone with an Addiction, Towards Treatment

Top 5 Tips to Motivate Someone with an Addiction, Towards Treatment

1. Empathize, don’t criticize. Every time you point a finger, you could be pushing your loved one farther away. Ask questions and listen.There is great power in a supportive loved one communicating with empathy and without judgement.

2. Be firm but fair. Specify some ground rules. Make it clear to them that you will not support their addictive behaviour, and try to set healthy boundaries. With these boundaries in place, they may just be motivated enough to start thinking about quitting.

3. Tell them how you feel. Sometimes, a person living with addiction may not realize how their behaviour has affected you and others in their life. Don’t be afraid to share your feelings with them; doing so could show a significant level of care and support.

4. Use “I” statements. As you express your emotions to your loved one, make sure not to point fingers or fault toward them. They already suffer from their own guilt and shame, so you may risk them shutting down completely. Rather than passing blame and telling them what they did, turn it back around to you. Making statements using “I feel” instead of “you” can help promote healthy communication.

5. Address their fears. A huge factor in resisting treatment is fear of the unknown. Hop onto our site and educate yourself. Knowledge is power when it’s time to have that conversation.

8 Ways to Support a Loved One Living with PTSD

8 Ways to Support a Loved One Living with PTSD

1. Don’t pressure them to talk about their PTSD. It can be challenging for people to talk about their traumatic experiences, triggers, and symptoms.

2. Engage in recreational activities together. Walking, running, board or card games, puzzles, or regular lunch dates with friends and family.

3. Let your loved one take the lead. It’s okay to take the back seat and simply let your loved one know you are on their side, and that you’re here to support them in their time, so they can live the meaningful life they want to lead.

4. Manage your stress. The more calm, relaxed, and present you are, the better you’ll be able to help the person you care about.

5. Be patient. Remember that recovery from PTSD is a process that takes time. It also often involves setbacks. Stay positive and remember that recovery doesn’t occur in a perfectly straight line.

6. Educate yourself about PTSD. The more you know about the symptoms, effects, and treatment options, the better equipped you’ll be to understand what someone you care about is going through.

7. Expect mixed feelings. Supporting a loved one through difficult times can come with a range of mixed emotions. It is okay to get frustrated or feel afraid or uncertain about what is happening to them.

8. Take care of yourself – by continuing to engage in activities that you enjoy, connecting with your own support network and obtaining the services of a therapist or counsellor whose role is to support YOU. This can feel selfish at times, but it is important to remember that we are most helpful to others when we are healthy ourselves. (Source: Homewood Alumni Homeweb)

Coping with Childhood Trauma from Past Abuse and Neglect

Coping with Childhood Trauma from Past Abuse and Neglect

In this article, we’ll be exploring the topic of past childhood trauma. While we always intend to be helpful when presenting information, we only encourage you to proceed if you recognize how this could affect you. Only you know best if it’s something you want to continue with. Please remember that if you have experienced past childhood trauma personally, we want to encourage you to take breaks while reading, especially if you are feeling uncomfortable or strongly react to what we’re sharing. We’ve included some resources near the end of the article that you may want to consult.

Many of us have experienced challenging moments in our lives. Memories of past childhood trauma may not be immediately obvious or apparent. They are often repressed in our minds or we may make a conscious effort to avoid thinking about these memories because they cause such a strong emotional response in us. While scientists are still researching and determining the complexity of connections between traumatic experiences and memories, “experts in child psychology argue that the memories formed from infancy to the age of 2 or 3 are very unlikely to be recovered.” (1)

We will look at how to recognize childhood trauma, find out how commonplace it is, and learn about some of the trauma people might have experienced that they have held on to and how it is affecting their adult lives. Then, we will talk about how repressed trauma may appear in adulthood and what our reactions to discovering it might involve. It’s important to understand that trauma is unresolved stress and does not become your identity. With the right understanding, practical coping tools, and a framework resolution, you can move forward and heal from these events to live well and feel better.

What is childhood trauma?

Childhood trauma is stressful experiences, such as abuse, neglect and household dysfunction, that occur before age 18. Traumatic experiences usually involve situations where children feel threatened either physically, emotionally or both. Trauma is highly individualized because not everyone is affected by the same things or in the same ways. That makes it quite challenging to determine the exact causes. However, studies show that childhood trauma can affect a person’s mental and physical health over time because our memories store both the events and the associated feelings/reactions.

What is a trigger for negative reactions?

When we don’t have an immediate frame of reference for something, our brains (whose primary purpose is to help us survive) may turn to memories of traumatic events. It can create an unexpected reaction. What’s happening is that we haven’t found a way to process and let go of the associated trauma. Our bodies, in turn, respond in several different ways:

- nightmares

- flashbacks

- confusion

- sleep disorders

- anxiety and panic attacks

- depression

- grief

- guilt

- shame

- nervousness in everyday situations

Attempts to try to address the trauma may lead to behaviours that are associated with a range of mental health conditions that could include:

- substance use

- self-harm

- eating disorders

- personality

- mood disorders

How common is childhood trauma, and how often does it occur? Are certain groups or people affected more than others?

Dr. Gabor Maté is a physician who has studied trauma’s connection to our health in a biopsychosocial context – how our health is affected by events we have experienced throughout our lives. He asserts that we need to acknowledge trauma because the interconnectivity between our psychology and physiology cannot be denied. (2)

Historically and currently, childhood abuse and neglect are often underreported for many different reasons ranging from children being generally unaware that what is happening to them is wrong, to being afraid to tell someone they trust what is going on. (3) In 2014, a General Social Survey conducted in Canada included questions about “maltreatment during childhood” for anyone over 15 to answer. It was ground-breaking because this study was the first-time data about childhood trauma and abuse had been collected nationally from adults. Here are some of the results: (4)

a.Those between the ages of 35 and 64 years of age at the time of the survey were the most common segment reporting abuse.

b.33% experienced physical or sexual abuse by someone over 18 or witnessed violence between known adults.

- More males (27%) than females (19%) experienced it and were almost twice as likely to report it. However, females were 3x more likely to have experienced sexual abuse before age 15.

- 65% of abused people reported occurrences between 1 and 6 times; 20% reported being abused between 7 and 21 times; and 15% reported abuse of at least 22 times,

- For 61% of respondents, parents and step-parents were responsible for the most severe physical abuse; but sexual abuse most often happened by someone outside of the family.

- 67% of victims never told anyone about the abuse.

c.40% of Indigenous people have experienced abuse compared to 29% of non-indigenous, and 42% of indigenous women have, compared to 27% of non-indigenous women.

d.48% of respondents who identified as members of the LGBTQ2 community reported having experienced abuse compared to 30% of heterosexuals.

e.Immigrants were less likely than non-immigrants to report a history of abuse as children. When abuse occurred, someone outside their family most often perpetrated it.

f.Drug and alcohol use were twice as common for people who had experienced childhood abuse.

g.There were negligible differences between people who had experienced childhood abuse when it came to education, employment, or income as adults.

Types of trauma

There are many different types of trauma that people have experienced.

Neglect

Neglect is where a child’s or teen’s needs are not attended to, exploited, pushed aside, or greatly resented. It can have immediate, short-term, and long-term consequences.

Neglect can be considered a general unawareness or systematic failure of a caregiver to respond to a child’s needs because they were overwhelmed or preoccupied. It’s often unintentional, perhaps reflecting low awareness and emotional intelligence or even a remnant of intergeneration trauma. In some instances, basic needs could be provided by caregivers, but it’s the emotional and psychological needs that are not. Sometimes it’s a case of caregivers “mishand[ling] one key area of support.” (5) For example, a child could be experiencing a lack of:

- comfort

- nourishment

- shelter

- medical care

- emotional support

- education

- caregiving (leaving a child alone or in the care of a third party who cannot provide adequate care)

- general resources such as food and clothing or even love when they are part of a large family

Neglect can be a “failure to act or notice a child’s emotional needs,” which results in chronic emotional and psychological crises that can affect brain development. (6)

From the caregiver’s behaviour, a child learns that their needs are unimportant and that seeking adult support is often futile. In households with strict rules – such as no crying, no sadness, or no loud voices – the adults discourage natural, spontaneous responses from the child or teen. Instead, they should acknowledge that the child is likely instinctively expressing a need to feel close and share their emotions. By denying them the opportunity to process their feelings, these children grow up learning that mentioning these natural responses is something to fear. In the child’s adult relationships, this can manifest as mental and physical difficulties where they:

- feel low self-worth

- have low self-esteem

- display low confidence

- have trouble with loneliness

- are focused on perfectionism or avoidance, and

- find comfort in self-deprecation

Children also learn from caregiver behaviours such as being emotionally detached, anxious, or constantly worried.

Abuse

Abuse can be viewed as an intentional, conscious action or decision by a caregiver to deny a child care or harm them. In many circumstances, the abuse is physical or sexual. The abuse creates trauma.

Children who have experienced neglect and abuse are vulnerable to other traumatic events that are offshoots of the original trauma. It could be that they are threatened by, become involved in, or witness an event such as (7):

- bullying

- community violence

- multiple complex traumatic events

- natural disasters

- early childhood trauma that occurs before age 6

- intimate partner violence

- traumatic medical stress

- refugee trauma

- traumatic grief such as the loss of a parent or close caregiver, or family member

- the end of a relationship (divorce)

- having a learning disability

- having a caregiver with untreated mental illness

Recognizing the signs of unresolved trauma

Symptoms of unresolved trauma start when adults experience stress or when experiences remind us about something that happened when we were children. Adults who have experienced childhood trauma aren’t always able to recognize their own trauma because they have usually developed strong self-reliance and have often been the ones to build a solution to cope with these experiences independently.

As a result, it may be challenging to consider that symptoms of unresolved trauma may look like somewhat ordinary things. But these are often the body and mind’s ways of alerting us to problems that originated in childhood:

- Chronic pain – migraines, joint and nerve pain, back pain, fibromyalgia, etc.

- Fatigue – constant low energy, weakness, brain fog, sleepiness, etc.

- Digestive issues – nausea, diarrhea, constipation, IBS, etc.

- Hypersensitivity/Hypervigilance – awareness of sensations to sounds, lights, environments, etc.

- Anxiousness – increased heart rate, panic disorders, fears, etc.

- Depression – low moods, lacking motivation, feeling hopeless, etc.

Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE)

Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) is “used to describe all types of abuse, neglect, and other potentially traumatic experiences that occur to people under the age of 18 years.” (8) ACE scoring is a methodology to help adults reflect on situations that may have affected their development. ACEs have the potential to uncover symptoms of childhood trauma because an adult can better articulate whether they feel they’ve been able to deal effectively with the ACE. In fact, “one in every six adults experience at least four ACEs, according to the CDC. These experiences can be particularly harmful because they occur at such a vulnerable phase of growth. In early childhood, brain development and social-emotional growth are at a critical stage.” (9)

How to recognize if childhood trauma is affecting you as an adult

It’s important to realize that not all trauma is due to mistreatment or abuse. Children can experience frightening events in their lives, such as accidentally getting separated from their caregiver in a store or being startled and uncomfortable because of loud noises in their environment. They can also experience trauma when they experience something new or, for the first time, like visiting a doctor or dentist. These events can create memories associated with trauma, but the cause was not neglect or abuse.

Some professionals help people sort through types of traumas by helping determine whether they have experienced what they are referring to as Big T Trauma or Little t Trauma, which attempts to explore them in the context of how the event affected someone’s physical safety to produce the traumatic response. This approach can help someone determine if these experiences are affecting our innate sympathetic nervous reactions, also known as fight, flight and freeze.

Big T traumas are “generally related to a life-threatening event or situation…[like] a natural disaster, a violent crime, a school shooting, or a serious car accident,” but “chronic (ongoing) trauma, such as repeated abuse, can also qualify as big T trauma.” (10)

Little t traumas are “events that typically don’t involve violence or disaster but do create significant distress… [such as] a breakup, death of a pet, losing a job, getting bullied, being rejected by a friend group.” (11)

Common reactions to trauma

Framing childhood trauma may be difficult because we tend to discount the impact of events that happened to us in childhood. After all, they happened at a time in our lives when we didn’t have the evaluative tools, control, and self-determination that adults do to process situations.

Our adult perspective and viewpoints can also cloud or invalidate the child’s reaction to the trauma. For example, uncharacteristic responses from adult figures that may have been frightening to you as a child and perceived as threatening may not be viewed the same way today. There’s also a tendency to internalize responsibility for the caregiver’s actions, taking on blame for a situation and excusing the caregiver. It can be because, as a child, you were told you were responsible for that adult’s behavioural choices at the time.

Many adults also experience disassociations where they strategically avoid certain situations. Generally, it’s because they cause them discomfort as adults. An example of disassociation would be how as an adult, you can never be late, or it can cause you to panic. The root cause may be a childhood experience where a caregiver was late to pick you up. The emotions that the event made you feel may have influenced your development so that you unknowingly relive an unresolved traumatic experience from your childhood.

Ways to heal from childhood trauma

Now that we have looked at what trauma is, and unveiled how people may have experienced trauma, as well as abuse, it is time to look at ways which we can heal from childhood trauma. The following gives some strategies for healing.

- Learn to approach memories calmly and recognize and be curious about our automatic reactions. It is fundamental to learning about what triggers us, which can help process those triggers, removing their intensity over time.

- Try to fill in the blanks/gaps in memories by approaching them with storytelling. This method can help gently bring memories forward because it allows us to be more mindful as adults. We can leverage more emotional regulation tools that we have learned to understand these situations and process the experiences from a different perspective. It also helps us release the fearful associations and acknowledge how we can choose to remove the trauma, so it doesn’t continue to have a hold on our current lives.

- Explore a wide range of treatment options:

- CBT – cognitive behavioural therapy helps people re-think their thoughts and beliefs about traumatic events and activate healthy coping skills.

- DBT – dialectical behavioural therapy helps to build skills in responding to stressors and emotional regulation.

- EMDR – eye movement desensitization and reprocessing helps retrain areas of the brain that hold traumatic experiences by following a series of specific eye movements performed under the direction and guidance of an EMDR therapist.

- Somatic Experiencing (or similar types of therapy) – create positive mind/body connections that help reset the nervous system. These could include treatments such as:

– Meditation

– Deep breathing

– Yoga

- Clinical EFT (Emotional Freedom Technique) focuses on stimulating acupressure points in the body with a repeated light touch.

- Clinical Myofascial Release focuses on specific guided motions to expand and contract tissues that relax and release tension and trauma.

Childhood trauma resources

You may want to review some of the most innovative thinking about childhood trauma from people who have extensively studied links between it and health as adults. They advocate for different approaches for physicians to acknowledge and address trauma’s effects on our lives.

- Dr. Gabor Maté has written several books on the topic, including the recent release “The Return to Ourselves: Trauma, Healing and the Myth of Normal”

- Dr. Bessel van der Kolk created the National Child Traumatic Stress Network https://www.nctsn.org and has published a book about trauma titled “The Body Keeps the Score”

- Dr. Nadine Burke Harris gave a TED talk: “How childhood trauma affects health across a lifetime, “where she discussed studies prepared by the Centres for Disease Control (CDC) and Kaiser Permanente. She has published a book titled, “The Deepest Well: Healing the Long-Term Effects of Childhood Adversity”

We have also included links to some Adverse Child Experience (ACE) Questionnaires that you may be able to explore as you begin working on healing from childhood trauma.

- ACE Questionnaire from The Canadian Association for Mental Health, CAMH.

- Finding your ACE score from the National Centre for Juvenile Justice, Family Violence and Domestic Relations, and Child Welfare and Juvenile Law NCJFCJ

Above all, please be gentle with yourself as you explore your childhood trauma. It can be a difficult, lengthy, and complicated process to work through as an adult, and you may find that you are not ready to talk about it. Remember that you don’t need to figure everything out alone. Taking time and space to heal is one of the most significant gifts you can give yourself.

References:

1. Positive Kids n.d). The Child Psychology of Abuse and Repressed Memories. PositiveKids.ca. Retrieved February 10, 2023 from https://positivekids.ca/2017/01/09/the-child-psych…

2. Maté, G. (2023 February 22). George Stroumboulopoulos in conversation with Dr. Gabor Maté Live on Instagram. Instagram @strombo, @gabormatemd.

3. Burczycka, M. (n.d.). Family Violence in Canada: A statistical profile, 2015, Section 1: Profile of Canadian adults who experienced childhood maltreatment. Statistics Canada. Retrieved February 10, 2023 from https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/85-002-x/20170…

4. Ibid.

5. Holland, K. (Medically reviewed by Legg, T.J., PhD, PsyD.) (2021 October 21). Childhood Emotional Neglect: How It Can Impact You Now and Later. Healthline.com. Retrieved February 10, 2023 from https://www.healthline.com/health/mental-health/ch…

6.Ibid.

7. The National Child Traumatic Stress Network. (n.d.). What is childhood trauma? Trauma Types. The National Child Traumatic Stress Network (NCTSN.org). Retrieved on February 10, 2023 from https://www.nctsn.org/what-is-child-trauma/trauma-…

8. Su, Wei-May & Stone, Louise. (2020 July). Adult survivors of childhood trauma: Complex trauma, complex needs. Australian Journal of General Practice (AJGP). Volume 49, Issue 7. Retrieved on February 10, 2023 from https://www1.racgp.org.au/ajgp/2020/july/adult-sur…

9. Newport Institute. (n.d). Big T vs. Little t Trauma in Young Adults: Is There a Difference? Newport Institute.com. Retrieved on February 10, 2023 from https://www.newportinstitute.com/resources/mental-…

10. Ibid.

11. Ibid.

It's not Just you. The Post-Pandemic Workplace is Stressful for Everyone

It's not Just you. The Post-Pandemic Workplace is Stressful for Everyone

Whether it takes place at home, in an office, or out on the front lines, work can be a stressful experience. In fact, Canadian workers are among the most stressed in the world.

“A lot of people don’t even realize they are experiencing moral distress. They have this general sense of outrage at the system and don’t see it for what it is.”

Work-related stress existed long before the pandemic, but it rose to new heights as our workplace fundamentals changed overnight. While the terrifying uncertainty of the early pandemic is now far behind us, the aftershocks continue to impact our mental wellbeing.

A Capterra survey found that while the percentage of Canadian employees reporting negative mental health quadrupled during the pandemic, that percentage hadn’t diminished in 2022. In fact, it had increased very slightly.

A 2022 Gallup report found that Canada is one of the most stressed regions of the world. In 2022, 44% of employees saying they experienced stress a lot of the previous day—the highest percentage in a decade.

Workers of all types are feeling stressed

Whether you perform your job remotely, on site, or on the front lines, you may be feeling work-related stress.

Nearly one in five workers in Canada are now fully remote, and while many people enjoy this work style, for others, it has created feelings of isolation and blurred the boundaries between work and life in an unhealthy way. A 2022 survey by Cisco found that stress levels had increased for more than one in five remote or hybrid workers (22%).