How to be an Ally

How to be an Ally

Being an ally is about far more than making a declaration. It’s a conscious, educated decision that leads someone to develop sincerity, focus on introspection, and learn about consistency.

True allies show solidarity for people whose circumstances are different and challenging. There should never be any expectation of recognition or gratitude. An ally must understand this and embrace it. Embracing allyship helps you realize how you live your life and can support earnest changes in behaviours in yourself and society that can contribute to shifts that chip away at injustices and inequities.

In this article, we will explore some of the fundamentals, clarifying what it means to make the personal decision to be an ally and why allies are necessary. We’ll also look at the actions allies can take to strengthen our workplaces and communities.

What is an ally?

An ally is someone who wants to partner with marginalized people in our society to help overturn oppression and inequities that center around topics such as race, cultural identity, gender, religion, sexual orientation, ability, and body type/appearance. Allies focus on standing up “for equal and fair treatment of people different from them” whose voices are underrepresented.[1]

Allies recognize that introducing consistency in their lives can result in solidarity with others because they approach things earnestly, knowing that the right kind of support can change behaviours and ideas. Allyship is most effective when it happens in the context of genuine relationships and everyday interactions.

A large component of being a successful ally is practicing self-awareness and self-accountability.

- An ally must acknowledge how their privilege has benefited them.

- They must be open to listening to understand and learn about the kinds of meaningful actions they can offer as a show of support for people lacking privileged advantages.

Another way to look at it is that an ally cares enough to make a conscious decision to support someone who is a member of a group that the ally is not a part of and who is having a negative experience in their life. They also recognize that allyship is not pity. When enough people decide to be allies, that’s the point where social and societal change begins to happen.

Allyship is only valuable if it’s consistent. It can also be contradictory if the ally enters a situation from a solutions-oriented perspective because they believe they know exactly how to fix a problem. The responsibility for learning about the challenges marginalized groups experience is not something for an ally to expect their marginalized contacts to offer. It’s up to the ally to seek accurate knowledge responsibly. An ally must self-educate consistently and without expecting recognition for their involvement.

Why are allies necessary?

We often adapt what we think, say, and do to blend in with the crowd. It can help us feel accepted, safe, and that we belong, leading us to behave in specific ways, like others in the group, so that we aren’t asked to leave it. Psychologist Robert Cialdini observed that “people copy the actions of others to know how to act in a certain situation. This idea stems from the assumption that if other people are doing something, it must be the correct thing to do.”[2] What’s interesting is that we tend to conform even when we observe or experience something that we know is wrong. The people around us subtly influence us: social actions and opinions are contagious, both good and bad.

Allies dare to reflect and recognize their privilege and use it to “influence inclusion and call out or challenge behaviour [that perpetuates] bias and systematic oppression based on race, gender, sexual orientation and ability.”[3]

What actions can you take to become an ally?

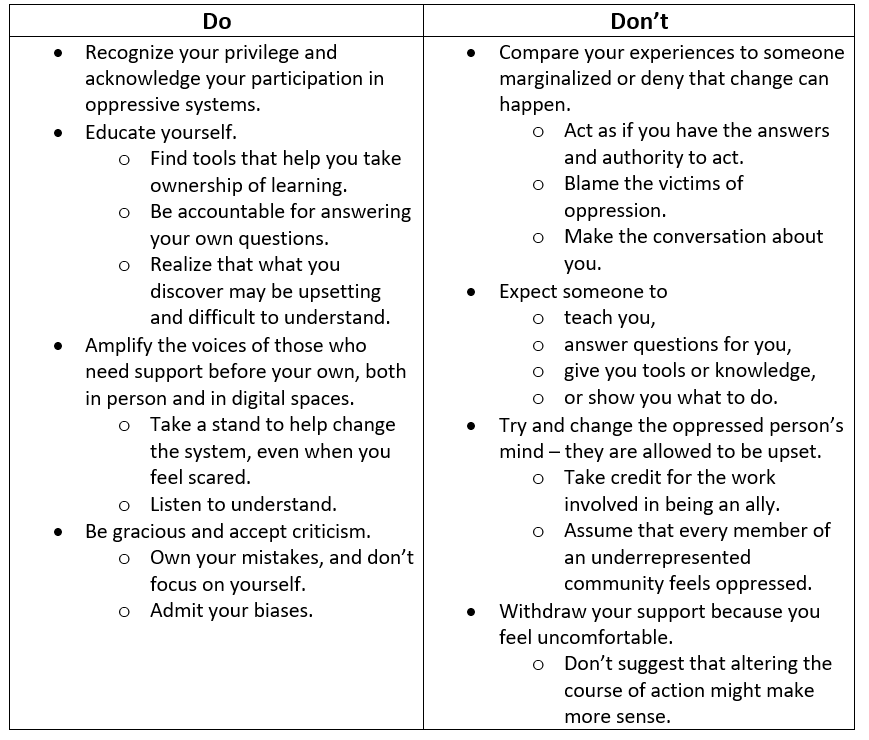

Being an ally comes with great responsibility. Here are some considerations:

How can you be a better ally in the community?

Being present as an ally is about consistency. Show up for all people and groups, observing that each may take a unique approach. An example of a simple action you can take is to acknowledge important holidays and milestones.

Recognize that you might be the one who needs to change or stand up for change to correct a misperception. Pay close attention to language and ideas to reflect that in conversations to show you care. Stand up to discrimination when you see it by modelling active listening. For example, take time to learn the correct pronunciation of people’s names. You could also support someone’s expertise and skills and invite them to share their knowledge within the community.

You also need to respect boundaries. Some people may adapt their behaviours for safety reasons. Don’t chastise them for doing that. Follow their lead and try to understand why they are making that choice. Think about what a shift in behaviour in the future could do that might result in a safer experience for them.

How can you be a better ally at work?

You can start by recognizing that there are inequities in the workplace that affect people’s physical and mental health significantly. These might be centred around income and lifestyle or other factors that affect the identity they portray at work and their ability to be their authentic self.

Known issues include:

- Unequal pay

- Lack of diversity

- Underrepresentation of people in marginalized groups in management/leadership positions

Remote work adds another complication. It’s easy for people to make assumptions about one another when their interactions are virtual. The lack of physical presence can introduce microaggressions that often have remote workers feeling excluded and undervalued.

Allies can help push for changes by actively advocating and participating in these approaches to ensure that concerns are discussed and not diminished.

Create space for productive discussions

Be willing to have and support uncomfortable talks, even if the topics are controversial. It holds the organization accountable for addressing Diversity Equity and Inclusion (DEI) issues, especially if HR policies are already in place.

Develop mentorship opportunities

Supporting allyship can be strategic, allowing people to become “collaborators, accomplices, and co-conspirators who fight injustice and promote equity” through the relationships that develop and actions taken during mentoring.[4] It can be the catalyst to drive change.[5]

Use a strategic and measurement-based approach

Engage in ongoing measurement to evaluate if your DEI policies are effective. This includes creating annual or quarterly plans that outline DEI initiatives that drive or align with the organization’s strategic plans; defining who is accountable for the initiatives, establishing and analyzing key performance metrics to assess the impact of initiatives and programs and incorporating on-going feedback from leaders and employees.

Change the usual ways feedback about DEI issues is collected

Allies can encourage people to share what the organization should start doing, stop doing, and stay doing. Keeping things simple can help everyone feel safe sharing their realities and bringing transparency to what is happening at work. People never want to feel like they are the only ones sharing their situations. There should be zero tolerance for inequity and discrimination.

References:

[1] Wells A. & White B. (2021 February 4) Why is Allyship Important? National Institutes of Health (NIH). Retrieved April 27, 2023 from https://www.edi.nih.gov/blog/communities/why-allyship-important

[2] Cherry, K. (2022 January 20, Updated 2023 March 5). Confirmity: Why Do People Confirm? Explore Psychology. Retrieved April 27, 2023 from https://www.explorepsychology.com/conformity/

[3] Rice, D. (2021 August 18). The Keys to Allyship: Understanding What an Ally Is and the Role They Play in an Inclusive Workplace. Diverity Inc. Powered by FAIR360. Retrieves April 27, 2023 from https://www.fair360.com/the-keys-to-allyship-understanding-what-an-ally-is-and-the-role-they-play-in-an-inclusive-workplace/#:~:text=In%20majority%2Dwhite%20societies%2C%20effective,privilege%20to%20drive%20tangible%20change.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

The Intersection of Sexual Identity and Mental Health

The Intersection of Sexual Identity and Mental Health

If someone were to ask you who you are, how would you answer that question? We would likely share the things that we instinctually feel form our identity and are essential for us to express. However, we would also likely assess the environment and situation we find ourselves in first to determine the degree of information to share. We gauge other people’s potential interests, determine if we are meeting them for the first time, whether alone or in a group, and collect details about the setting, their appearance, tone of voice, and facial expressions that give us clues. What we say is selective and doesn’t necessarily share every profound aspect of our life experience that has contributed to forming our identities to date at that moment, but rather those that are most important to convey a picture for them to receive and develop quickly to understand.

We can consider all the people, situations, and circumstances that help us determine our identities are like the spokes of a wheel. Ultimately, they converge and intersect at a central point of strength that holds them all in place, the hub. That is our essence, our sense of self: our identity.

In this article, we will look at how intersectionality is an approach to use in many aspects of our lives to develop a greater understanding of sexual identity and mental health, especially in the context of how different points of intersection affect the experiences of marginalized groups within our society. Opening our points of view can help us learn more about ourselves and other people and enhance our understanding so that we can all strive to live well and feel better.

What is intersectionality?

Intersectionality is a way to look at all the different aspects of someone’s life that have influenced them and their experiences. For example, considering where they grew up, where they live now, what their childhood was like, how they were affected by their families and culture, and whether they have had economic advantages that have increased their social standing would all factor into creating both inequalities and power.[1] However, some influences can be even more critical in developing someone’s social standing where “divisions such as gender, ethnicity, class and lifecourse positioning” are likely to shape more people’s lives than others.[2] Researchers have discovered that the social divisions experienced have a more lasting role in influencing a person’s life.[3] Intersectionality as an approach examines how multiple “forms of discrimination…and oppression, like racism, sexism, and ageism might [also] be present and active at the same time in a person’s life.”[4]

The importance of taking an intersectional approach to sexual identity and mental health

Studies are starting to explore how important it is to view intersectional aspects of our identities through a multi-factor lens. Evidence shows how various health conditions are treated socially and by healthcare providers and systems. Overall, there needs to be a focus on reducing the “burden of stigma.”[5]

The intersection of sexual identity and mental health tremendously influences someone’s sense of belonging and identity. But it’s also important to understand that looking at points of intersection should not be limited to comparing only two tangents because it’s the “convergence of multiple systems of oppression that together underlie the ways the ways that individuals interact with the world around them and how they are treated by others.”[6] For those in the LGBTQ2S+ community, where there is a continuum of many sexual identities and genders, in addition to “diverse racial and ethnic groups, differing abilities, and a range of socioeconomic backgrounds” it is vital to acknowledge that divisions and negative connotations present in society make it exceptionally difficult for members to navigate their lives confidently and safely, especially when it comes to obtaining high quality, purposeful healthcare.[7] Negative health outcomes are compounded for LGBTQ2S+ individuals experiencing other forms of discrimination, including racism, colonialism, and ableism. Practitioners may be unaware of how unconsciously managing a case, instead of approaching a situation from a person-centric point of view, can create trauma for someone seeking medical care.

What do we know about mental health in LGBTQ2S+ communities?

Research shows that people in LGBTQ2S+ populations are affected by discrimination, marginalization, and harassment and, therefore, “often experience greater frequency of mental health problems as a result.”[8]

They are:

- more likely to experience depression, anxiety, suicidality, and substance abuse

- at double the risk of developing post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

LGBTQ2S+ Youth:

- experience risk of suicide and substance abuse at levels 14 times higher than their heterosexual peers

- 77% of trans respondents in one survey had seriously considered suicide

- 45% had already tried to end their lives

- trans youth and those who had experienced physical or sexual assault were at greater risk

Statistics also showed that:

- bisexual and trans people are over-represented among low-income Canadians

- trans people reported high levels of violence, harassment and discrimination when seeking stable housing, employment, health, or social services[9]

How does sexual identity interact with other social identities to shape bias?

One of the most significant challenges LGBTQ2S+ communities face is that, historically, the full spectrum of sexual identity has been associated with mental illnesses. The American Psychological Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Illnesses (the DSM-5) is the guidebook many professionals use to diagnose mental health disorders. However, “until 2013, being transgender was still considered a mental illness, and being gay or lesbian was considered a mental illness until 1973.”[10] Biased views and opinions about sexual identity are embedded and endemic in the fabric of the healthcare systems and governments.

The reality that many people face in terms of stigma is that living their authentic identities, which happen to be on a different position from heterosexism in a broad spectrum of sexual identities, often results in them being[11]:

- rejected by their families

- rejected by society

- vulnerable to violent acts

- forced to live with daily microaggressions in their homes and workplaces

- self-critical and experiencing negative emotions such as shame and guilt

- isolated

- chronically stressed

- anxious

Why do LGBTQ2S+ communities experience health disparities?

People whose sexual identity is on the LGBTQ2S+ spectrum face disparities in obtaining unbiased healthcare regularly. These can be related to harassment, where people are subjected to microaggressions, trauma, or violence. They can also face racial discrimination or even rejection from their families and society for what is sometimes perceived as a lifestyle choice. Finally, they can be affected by structural inequalities, including facing barriers to accessing mental health care and receiving a lower quality of care when treated.

Mental health risks for LGBTQ2S+ communities

People experience trauma, sometimes called “minority stress,” when they must repeatedly deal with discrimination and stigmatization to live their lives.[12]

For example, they might:

- Have to “come out of the closet” on multiple occasions, or sometimes daily

- Feel they need to “go back into the closet” to receive some care such as eldercare, long-term residential care, or palliative care

- Have their sexual orientation or gender identity revealed against their will in social settings or to their families

- Need to assess a situation carefully to determine if it is safe to disclose their authentic sexual identity

Minority stress is directly linked to psychological distress and higher suicide risk amongst LGBTQ2S+ communities. It can also contribute to the earlier onset of chronic diseases.[13]

Simply hearing repeatedly about hate crimes, violence, and anti-LGBTQ2S+ legislation can affect health and self-esteem, leading to depression or anxiety.[14]

As a result, people who identify as LGBTQ2S+ have an increased chance of developing more severe substance use and addiction complications because of increased frequency of mental distress, depression, self-harm, eating disorders, suicide, and IV drug use.[15]

How community supports and peer groups can help

People need to feel included in society and their communities, be free from discrimination and violence, and have access to economic resources to help them maintain positive mental health and well-being.[16] However, change and support also come from looking at intersecting factors as part of a more comprehensive approach to mental health treatment. Doing so can “help identify service gaps and prevent or reduce further harm.” [17]

We all have a role in challenging heterosexism, transphobia, and systemic forms of oppression. These are keys to improving mental health outcomes within LGBTQ2S+ communities.

- It can start with developing a better approach to sex education that is age appropriate and includes teaching about sexual diversity, gender identity, sexual health and diseases, and mental health, and addresses intersectionality as part of the standard school curriculum.

- Gay-straight alliance groups help build inclusion and save lives, especially for people who do not have support from families or schools.[18]

- Having safe places to meet, build community and reduce social isolation by supporting healthy connections is essential.[19]

What can people do to improve their mental health?

Improving your mental health can start with small, simple changes:[20]

- Connect with others who can relate to your circumstances, will accept you and provide emotional support

- Unplug from news and social media to reduce stress and fatigue that can lead to feeling hopeless, worried and fearing for personal health and safety

- Prioritize your physical health with good nutrition, restful sleep, and regular exercise. These will also help boost your mood and increase your energy

- Pursue creativity to express your feelings. It can help increase focus, ground you in the present and help you feel proud and accomplished

- Set boundaries so you are not faced with situations that compromise your physical or mental health. You don’t need to respond, and leaving an upsetting situation is okay

- Talk to professionals who can connect you with resources and supports to help you manage your emotions and mental health

Mental health resources for LGBTQ2S+ communities

We’ve compiled some resources that can help. Feel free to explore them while focusing on living well and feeling better.

Canadian

- itgetsbettercanada.org

- The Canadian Centre for Gender + Sexual Diversity | ccgsd-ccdgs.org

- Egale Canada | egale.ca

- Government of Canada: The human rights of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, 2-spirit and intersex persons

U.S.

- The Trevor Project | thetrevorproject.org

- The National Queer & Trans Therapists of Colour Network |nqttcn.com

- Human Rights Campaign: Tools for equality and inclusion. | hrc.org/resources

References:

1. Hopkins, P. (2018). Feminist geographies and intersectionality. Newcastle University. Retrieved March 24, 2023 from https://eprints.ncl.ac.uk/file_store/production/246036/DAEDDA02-4DB2-4B18-9120-7515E81E915F.pdf

2. Yuval-Davis (2011), as cited in Hopkins, P. (2018). Feminist geographies and intersectionality. Newcastle University. Retrieved March 24, 2023 from https://eprints.ncl.ac.uk/file_store/production/246036/DAEDDA02-4DB2-4B18-9120-7515E81E915F.pdf

3. Hopkins, P. (2018). Feminist geographies and intersectionality. Newcastle University. Retrieved March 24, 2023 from https://eprints.ncl.ac.uk/file_store/production/246036/DAEDDA02-4DB2-4B18-9120-7515E81E915F.pdf

4. Hopkins, P. (2018) What is Intersectionality? (00:11-00:22) Vimeo. Retrieved March 24, 2023 from https://vimeo.com/user83638171

5. Turan et al. (2019). Challenges and opportunities in examining and addressing intersectional stigma and health. BMC Medicine. Retrieved March 24, 2023 from https://bmcmedicine.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12916-018-1246-9

6. Yale School of Public Health (2022) Yale LGBTQ Mental Health Initiative: Intersectionality. Yale School of Medicine. Retrieved March 24, 2023 from https://medicine.yale.edu/lgbtqmentalhealth/projects/intersectionality/

7. Ibid.

8. Massie, M. (2020) A Facilitators Guide: Intersectional Approaches to Mental Health Education. UBC Workplace Health Services and Health, Wellbeing and Benefits). Retrieved March 24, 2023 from https://wellbeing.ubc.ca/sites/wellbeing.ubc.ca/files/u9/Facilitator%20Guide%20-%20Intersectionality%20and%20Mental%20Health.pdf

9. CMHA (n.d) Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans & Queer identified People and Mental Health. Canadian Mental Health Association. Retrieved March 24, 2023 from https://ontario.cmha.ca/documents/lesbian-gay-bisexual-trans-queer-identified-people-and-mental-health/

10. Massie, M. (2020) A Facilitators Guide: Intersectional Approaches to Mental Health Education. UBC Workplace Health Services and Health, Wellbeing and Benefits). Retrieved March 24, 2023 from https://wellbeing.ubc.ca/sites/wellbeing.ubc.ca/files/u9/Facilitator%20Guide%20-%20Intersectionality%20and%20Mental%20Health.pdf

11. Ibid.

12. Standing Committee on Health (Bill Casey, Chair) (2019). The Health of LGBTQIA2 Communities in Canada. House of Commons, Parliament of Canada. Retrieved March 24, 2023 from https://www.ourcommons.ca/Content/Committee/421/HESA/Reports/RP10574595/hesarp28/hesarp28-e.pdf

13. Ibid.

14. Collins, D. (2022). 6 Ways to Protect Your Mental Health as an LGBTQ+ Individual. One Medical. Retrieved March 24, 2023 from https://www.onemedical.com/blog/healthy-living/6-ways-protect-your-mental-health-lgbtq-individual/

15. National Institute on Drug Abuse (n.d). Substance Use and SUDs in LGBTQ* Populations. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; National Institutes of Health; National Institute on Drug Abuse; USA.gov. Retrieved on March 24, 2023 from https://nida.nih.gov/research-topics/substance-use-suds-in-lgbtq-populations

16. Ibid.

17. Ibid.

18. Standing Committee on Health (Bill Casey, Chair) (2019). The Health of LGBTQIA2 Communities in Canada. House of Commons, Parliament of Canada. Retrieved March 24, 2023 from https://www.ourcommons.ca/Content/Committee/421/HESA/Reports/RP10574595/hesarp28/hesarp28-e.pdf

19. Ibid.

20. Collins, D. (2022). 6 Ways to Protect Your Mental Health as an LGBTQ+ Individual. One Medical. Retrieved March 24, 2023 from https://www.onemedical.com/blog/healthy-living/6-ways-protect-your-mental-health-lgbtq-individual/

Indigenous Peoples and Trauma

Indigenous Peoples and Trauma

Colonial trauma has been part of Indigenous peoples’ lives since the first Europeans arrived and established permanent settlements in Turtle Island, the area now known as Canada. Unfortunately, Indigenous Peoples experience discrimination such as microaggressions that surface in any number of daily routine interactions, including with coworkers. In many cases, empathy and understanding are overshadowed by stereotyping, myths, misinformation, cultural appropriation, and insensitivity.

This article will briefly touch on some of the effects that many of us aren’t aware of regarding Indigenous Peoples, such as how the lasting effects of intergenerational trauma affect mental health. We must note that we are using the term Indigenous, which includes First Nations, Inuit, and Métis people. We know that there is a rich diversity within each group, especially concerning identities, traditional lands, history, language, and culture. While we can’t address everything within a single article, we can touch on what we believe are some important catalysts tied to the colonization experiences that all these groups share that have affected their overall health and well-being. We aim to help individuals begin to develop an understanding of the issues and start to navigate through the complexities. We believe that workplaces need to demonstrate sincerity and provide supportive tools that meet the needs of Indigenous Peoples. It’s a way to start walking together on a path towards reconciliation and healing.

A brief history

Indigenous Peoples are the original inhabitants of the lands within a geographic region. Before the arrival of European settlers, their distinct cultures, traditions, languages, spirituality, economies, and politics had flourished for tens of thousands of years. (1)

Arrival of Europeans

Norse explorers landed in the 11th century, though they did not stay more than a few years. (2) European settlers arrived in the 15th and 16th centuries and began early trade and commerce with Indigenous Peoples. (3) The European explorers travelled under the Doctrine of Discovery; an international law issued by Roman Popes in 1455 that effectively authorized them to lay claim to what they perceived to be vacant land in the name of their sovereign. Upon arrival, the lands certainly weren’t vacant. But one other article within the Doctrine permitted explorers to determine lands used “properly,” meaning running under Euro-centric laws. If they decided that wasn’t the case, they believed that God had brought them to the land to make a claim for the Crown based on their obligation to “civilize” the people. It was the beginning of colonialization where explorers took ownership of the lands and followed through on their perceived obligation to provide all non-Christians with education and religion. The Doctrine of Discovery has never been renounced. Instead, it served as the foundation for the Indian Act. (4)

The Indian Act

The Indian Act (1876) established governmental control over nearly all aspects of First Nations people’s lives to force them to assimilate into the Dominion of Canada as quickly as possible. (5) The Indian Act consolidated many pre-Confederation laws and created reserved land (reserves) and the promise to deliver food, supplies and medicines to these communities. Indian Agents maintained enforcement. The Act was intentionally restrictive and destructive to Indigenous culture and people. While there have been some amendments to the Act, overwhelmingly, the legislation is still highly paternalistic and continues to affect people today. (6)

This legislation has created many hardships because of its restrictiveness. Two significant aspects are rooted in much of the trauma Indigenous Peoples have experienced in the 21st century. (6)

- Determining an Indigenous Person’s “status” or “non-status” dictates the government’s obligation to care for them. The Indian Act includes information for First Nations people who are registered under the Act. Inuit or Métis people are not included under the Indian Act. Amendments to The Act have been attempting to rectify unjust practices. For example, Bill S-3, enacted on August 15, 2019, has attempted to eliminate “all known sex-based inequities.” (7) For example, in The Act, women who had married non-Indigenous men were denied status. (8)

- School-age children were forced to attend residential schools under the pretense of obtaining their “proper” education. The schools were designed to intentionally sever ties between Indigenous children and their families, language, identity, and culture. (9)

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

Alarming and frightening experiences can result in someone developing Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). The response to memories or associations with harmful events such as images, sounds, smells and emotions, causes them to react with a debilitating stress response. For Indigenous Peoples, “repeated exposure to trauma, family instability, and childhood adversities such as separation from parents, poverty and family dysfunction” presents an increased risk of developing PTSD. (10) Extreme stress can result in behavioural and, in some cases, even genetic changes as our bodies and minds try to cope with what has happened. We may not even be aware of the effect of the trauma until years later. (11)

The reality is that Indigenous communities are “dealing with higher rates of mental and social distress (trauma)” that can be “traced back to abuses experienced by…children who were forced to attend residential schools.” (12) There are generations of people who were disconnected from their families, communities, and culture for generations, to no fault of their own.

Understanding intergenerational trauma

Colonization events (the process of colonization), have led to “losses of culture, traditional values, and family stability…[because] in many cases, [opportunities] for parents and Elders to pass along vital cultural knowledge and resilience to children” were taken away. (13) It has created trauma that has been passed from one generation to the next. One researcher indicated that children and grandchildren of residential school survivors show an increased risk of anxiety and depression because they have experienced threats to their psychological health early on in their lives. (14)

It is helpful to have a fundamental understanding of Indigenous culture to realize how being disconnected from their communities’ left generations of Indigenous Peoples unsupported. Indigenous culture teaches how everything in our world is interconnected. In life, you are part of a community that cares for and shows respect to everyone and everything. In addition, there is recognition and appreciation for all relationships that exist: past, present, and future. Your family and Elders in the community would show you the importance of understanding, acknowledging, appreciating, and protecting humans; animals; plants (especially sacred medicines); air and wind; water; the sky; and the earth. (15) You would learn about the care of bundles that “can include sacred items such as feathers, drums, pipes, medicines, talking sticks and many other sacred items” that hold knowledge of their culture as “all that we are, all that we can be, and all that helps us to be holistic helpers.” (16)

When children were taken from their communities and sent to residential schools, they lost their families, communities, language, culture, and traditions. They experienced violence, starvation, abuse, and neglect. If they survived the experiences, they could not quickly re-integrate into their communities when they returned home and they had difficulty fitting in. They were unable to recognize their families including their parents and extended families. Instead, they showed signs of isolation and trauma as well as a loss of identity and belonging. They were fearful to disclose their experiences to anyone, because they were concerned about retribution from administrators. Further, if they were courageous enough to share what they had experienced or witnessed, their family members were doubtful because the truth contradicted what they had been told. (17)

Residential school survivors experienced a great deal of trauma which impacted their relationships. The trauma lead to a tremendous amount of pain and they were not provided with any support to learn how to deal with the pain they had endured. This led to utilizing unhealthy coping strategies such as substance use, self-harm including suicidal ideation and this also made them more prone to mental illness.

One of the many impacts of colonization on the Indigenous communities is intergenerational trauma. This continues to affect the Indigenous Peoples today. This is perpetuated in their parenting style which is often influenced by their experiences with the residential school system. Sometimes they resorted to what they had learned in residential schools, resulting in a new generation experiencing abuse, neglect, and violence. (18) Other times, they found themselves in the predicament of sending their own children to attend residential schools.

Then, the government stepped in again to try and fix these problems through social services. The Scoop (sometimes referred to as the 60s Scoop) was a practice of removing Indigenous children from their families to have them placed in foster care with non-Indigenous families, this happened to children between 1960 and 1990. There were more children removed from their culture, traditions, and families. (19) At the same time, residential schools continued. The last residential school closed in 1996. (20)

The Seven Generations Principle

Indigenous culture traditionally looked at the effects of a decision for the next seven generations. This principle is sometimes applied to how much work is ahead for Indigenous People’s to heal from the atrocities they have experienced. The first steps were sharing stories during the Truth and Reconciliation Commission Hearings and the government’s formal apology for creating and maintaining the residential school system. However, there is a long road ahead because Indigenous Peoples still experience injustices and racism daily. International events where the world comes together to support people experiencing conflict or for a common cause can be triggering and painful to observe because the same attention and dedication have not ever been displayed for Indigenous Peoples.

Healing from trauma

Indigenous Peoples may begin the healing process by:

1. Expressing a desire to heal and move forward.

2. Sharing truths and experiences with professionals and loved ones who want to help.

3. Accepting support, reconnecting, and reclaiming culture, language, traditions, spirituality, and values.

4. Using traditional medicines, sweat lodges and healing circles.

5. Embracing traditional ways of dealing with criminal acts and changing the experience of incarceration.

6. Learning from knowledge keepers.

What can non-indigenous people do to help?

The best things that non-indigenous people can do include:

1. Taking time to learn about Canada’s hidden colonial history.

2. Reading the Truth and Reconciliation Commission recommendations.

3. Learning about Indigenous customs, culture, history with a view of appreciation, not appropriation.

a. Attend pow wows and other educational events.

b. Read books and view films by indigenous authors about indigenous experiences.

c. Visit archeological sites.

4. Recognize your own biases and investigate myths and misinformation about taxes, housing, and education. Correct information when it is inaccurate.

5. Learn about and develop an awareness of discrimination such as microaggressions in language that perpetuate stereotypes and racialized beliefs.

The path forward

Indigenous and non-Indigenous people have a shared responsibility to listen, learn, and heal to promote decolonization. Together, we need to understand how traumatic events can bring up unintended feelings, frustration, and anger. At the same time, we need to work towards appreciation, respect, and understanding. Perhaps most importantly, non-Indigenous Peoples should not transfer the accountability for learning and sharing to an indigenous person. Remember that it’s not an Indigenous Persons role to educate you.

References:

1. Rutherford, A. (2017 October 3). A New History of the First Peoples in the Americas. The Atlantic, Science. Retrieved on March 15, 2022 from

https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2017/10/a-brief-history-of-everyone-who-ever-lived/537942/

2. Hansen, V. (2020 September 22). Vikings in America. Aeon. Retrieved on March 15, 2022 from

https://aeon.co/essays/did-indigenous-americans-and-vikings-trade-in-the-year-1000

3. Government of Canada. (n.d.). Highlights from the Report of the Royal commission on Aboriginal Peoples: People to People, Nation to Nation (1991). Government of Canada. [Section: Looking Forward, Looking Back.] Retrieved on March 15, 2022 from

https://www.rcaanc-cirnac.gc.ca/eng/1100100014597/1572547985018

4. Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. (2015 June). What We Have Learned: Principles of Truth and Reconciliation. Government of Canada.pp. 15-21. Retrieved on March 15, 2022 from

https://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2015/trc/IR4-6-2015-eng.pdf

5. BCCampus Open Education (n.d.) Pulling Together: Foundations Guide, Section 2: Colonization. BCCampus Open Education. Retrieved March 15, 2022 from

https://opentextbc.ca/indigenizationfoundations/chapter/the-indian-act/

6. Hanson, E. (2009) The Indian Act. First Nations & Indigenous Studies Program – The University of British Columbia. Retrieved March 15, 2022 from

https://indigenousfoundations.arts.ubc.ca/the_indian_act/

7. Government of Canada. (n.d.). About Indian Status. Indigenous Services Canada. Retrieved on March 15, 2022 from

https://www.sac-isc.gc.ca/eng/1100100032463/1572459644986

8. Crey K. & Hanson E. (2009) Indian Status. First Nations & Indigenous Studies Program. – The University of British Columbia. Retrieved March 15, 2022 from

https://indigenousfoundations.arts.ubc.ca/indian_status/

9. CBC News (2021 June 4) Your questions answered about Canada’s residential school system. CBC Explains. Retrieved March 15, 2022 from

https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/canada-residential-schools-kamloops-faq-1.6051632

10. Bellamy, S. and Hardy, C. (2015). Post-traumatic Stress Disorder In Aboriginal People In Canada. National Collaborating Centre for Aboriginal Health, Emerging Priorities. P. 12, para. 2. Retrieved on March 5, 2022 from

https://www.ccnsa-nccah.ca/docs/emerging/RPT-Post-TraumaticStressDisorder-Bellamy-Hardy-EN.pdf

11. van der Kolk, B. M.D. (n.d.) The Body Keeps The Score: Brain, Mind, and Body In The Healing Of Trauma. Retrieved on March 5, 2022 from https://www.besselvanderkolk.com/resources/the-body-keeps-the-score

12. Kirmayer et al. (2009), and Bopp, Bopp & Lane (2003), as cited in Bellamy, S. and Hardy, C. (2015). Post-traumatic Stress Disorder In Aboriginal People In Canada. National Collaborating Centre for Aboriginal Health, Emerging Priorities. P. 12, para. 5. Retrieved on March 5, 2022 from

https://www.ccnsa-nccah.ca/docs/emerging/RPT-Post-TraumaticStressDisorder-Bellamy-Hardy-EN.pdf

13. Elias (2012) as cited in Centre for Suicide Prevention (n.d), reviewed by Connors, Ed. PhD., Indigenous people, trauma, and suicide prevention. Centre for Suicide Prevention. Retrieved March 5, 2022 from

https://www.suicideinfo.ca/resource/trauma-and-suicide-in-indigenous-people/

14. Bombay, A., Matheson, K., & Anisman, H. (2014). The intergenerational effects of Indian Residential Schools: Implications for the concept of historical trauma. Transcultural Psychiatry. Retrieved March 15, 2022 from

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/1363461513503380

15. Partridge, C. (2010 November).Residential Schools: The Intergeneration impacts on Aboriginal Peoples. The Native Social Work Journal, Volume 7. Laurentian University Press. Retrieved March 15, 2022 from https://zone.biblio.laurentian.ca/bitstream/10219/382/1/NSWJ-V7-art2-p33-62.PDF

16. Health Standards Organization (2016). Bundles as Culturally Safe Practices. Fort Frances Tribal Area Health Services Sector. Retrieved March 5, 2022 from

https://healthstandards.org/leading-practice/bundles-as-culturally-safe-practices/

17. Partridge, C. (2010 November).Residential Schools: The Intergeneration impacts on Aboriginal Peoples. The Native Social Work Journal, Volume 7. pp. 48-54. Laurentian University Press. Retrieved March 15, 2022 from

https://zone.biblio.laurentian.ca/bitstream/10219/382/1/NSWJ-V7-art2-p33-62.PDF

18. CBC News: The National (2015 June 2). Stolen Children | Residential School survivors speak out. Retrieved March 15, 2022 from

https://youtu.be/vdR9HcmiXLA

19. Hanson, E. (n.d.) Sixties Scoop: The Sixties Scoop & Aboriginal child welfare. First Nations & Indigenous Studies, The University of British Columbia. Retrieved March 15, 2022 from

https://indigenousfoundations.arts.ubc.ca/sixties_scoop/

20. Jeganathan J & Lucchetta C. (2021 June 21). Felt through generations;: A timeline of residential schools in Canada. TVO. Retrieved March 15, 2022 from

https://www.tvo.org/article/felt-throughout-generations-a-timeline-of-residential-schools-in-canada

Teaching Inclusivity and Inclusive Language

Teaching Inclusivity and Inclusive Language

Think of a time when someone conveyed a message to you that you didn’t belong. The rejection may have been deliberate or incidental. The experience might have happened a long time ago or been only moments old. Suppose you were asked to recall how you felt. In that case, your description might include emotional references to hurt feelings, being crushed, or even feeling heartbroken. These expressions tend to use language that focuses on physical pain to talk about social rejection and with good reason. Researchers have found that being excluded activates our pain system. Neurologically we’re hardwired to use the same neural pathways for physical and social pain.1

To feel terrific, we must connect with others through social interactions that are welcoming. We all have the need to feel wholly accepted as individuals. We also need to know that we have equal footing with others, despite our differences. These are some of the broad fundamentals of inclusivity. It’s a way of interacting with people who have typically been marginalized to be supportive. It’s also what we’re focusing on this month.

What does it mean to belong?

We respond to the people and situations around us with a complex combination of emotions, intellect, instincts, and intuitiveness, but that’s not all. We build on this information with learned social behaviours and cultural influences.

It’s how we learn to live our lives both independently and interdependently. Studies show that our social environment profoundly shapes us. We tend to suffer when our social bonds are threatened or severed.2

Nearly everyone has experienced feelings of wanting to be included, of wanting to belong. If you don’t think it’s true,

what you can do is reflect on when you were younger and in school, specifically your gym class. Can you feel the nervousness that crept over you while you stood in a line across from people who were assigned the task of picking a team? Even if you were the athletic type, you can probably think of at least one time in your life when you worried that you wouldn’t be selected by the team you were hoping to join. For many, it was far worse. Some were afraid that they weren’t going to be picked at all. To be the last person meant that you were joining a team that had to take you by default rather than by choice. This nightmarish scenario has played out time and again for many people growing up. It was like a very public affirmation of whether you belonged or you were to be excluded. It hurt if it was the latter, and that pain likely extended into how invested you were in playing and enjoying the game. But if you were fortunate enough to be picked early on, you felt relief and were glad that someone had chosen you.

Inclusivity is essential in all our lives: without it, people are vulnerable to having poor mental health and experiencing feelings of loneliness and isolation. Often, healthy self-worth and self-esteem are tied to feeling included. When you feel like you don’t belong anywhere, it can lead to stress, anxiety, and depression.

At work, diversity, equity and inclusion programs are in part meant to recognize the links between inclusivity and health.

It can mean the difference between having a successful approach or whether ignorance, disregard, and fear of

losing power devolve into tokenism. When a workplace is trapped in a harmonious, conformist way of operating,

it’s not courageous enough to do the difficult work of assessing what barriers exist for people. While merely

going through the motions, companies will miss opportunities. When inclusivity exists, organizations

can experience game-changing insights, super-charged creativity and attract the most talented people to join

a group of happy and satisfied employees.

How do you create inclusive environments?

It helps to start with all the little everyday things, like the words you choose to use and how you interact in social settings. People can tell whether you are sincere, trying to be inclusive, and creating a sense of belonging for everyone. Simply tolerating someone who feels like they are on the fringe is inauthentic and certainly not being inclusive. The importance of getting inclusion right does not mean that you should be on a mission to be “indiscriminately inclusive” though.3 You need to recognize that equity, equality, and privilege are distinct.

- Equity is giving people the individualized tools and support they need to succeed.

- Equality is giving everyone the same thing.

- Privilege is when someone cannot realize that their experiences have given them an advantage over another person. Empathy is sacrificed for judgement and comparisons that push aside opportunities for self-reflection.

Often, in pursuit of demonstrating just how inclusive we are, we can become mired in political correctness. That, too, creates discomfort and stalls real progress towards building inclusive environments. We can believe that we are

well-equipped when we’ve learned a little bit about a subject and feel empowered to stand up for those who are being,

in our judgement, persecuted. There are fine lines between appropriation, appreciation, and allyship.

- Appropriation takes culturally significant elements from minority or marginalized group. It converts them into something that is devoid of meaning and diminished from the original intentions. It could involve clothing, icons, rituals, or behaviours and is often focused on power or profit by making them seem trendy, exotic, or desirable. Usually, the people appropriating feel entitled to do so and don’t realize that they are being insensitive.

- Appreciation is learning about culture to understand it and gain perspective and knowledge. There isn’t any intention to misuse something or claim expertise. Quite often, permission is sought before using any part of a culture to demonstrate respect.

- Allyship is a conscious choice to respectfully advocate, be supportive and accountable for helping people who feel like they don’t belong. The ally doesn’t benefit from their involvement in any way. They collaborate to achieve common goals.

Language is essential

Developing awareness of how we communicate and the language we use is key to helping create inclusivity. We use language to make connections with other people and establish belonging. It’s a fundamental of human interaction that we are constantly learning. Choosing to use inclusive language means that you are less likely to make someone

feel like they don’t belong. It frees people from using harmful words. Becoming conscious of phrases and euphemisms

you use that could make someone feel diminished will help you eliminate them. Don’t be afraid to point out problematic language when you hear it. Words and expressions that may have been popular at one time will only fade away when we hold each other accountable for the language we use. Choosing to use disrespectful language is aggressive.

It is important to remember that words can hurt deeply and may not easily be forgotten.

Much of our language is male-centric, which perpetuates detrimental stereotypes of both a speaker and their audience. Inclusive language is conscious and aware of this and avoids discrimination. For example, The United Nations has published a style guide for gender-inclusive language. It offers guidelines for using “non-discriminatory language” and “makes gender visible when it is relevant for communication.” It also advocates for not making gender visible when it is not relevant for communication.4 They provide examples using a scale of less inclusive versus more inclusive:

Less inclusive

- Mankind

- Manpower

- Man-made

- Guests should attend with their wives.

- Fathers babysit their children.

More inclusive

- Humanity

- Staffing

- Artificial

- Guests should attend with their partners.

- Fathers care for their children.

The best way to begin to evolve your language choices and speech patterns is to operate from a position of being respectful. It is not easy and will take conscious effort and practice and you will make mistakes. If you can find empathy, listen, and learn about how language constantly evolves, you may have an easier time. Becoming stuck in arguments about words being used to express collective and individual identities or freedom of speech/freedom of expression is counterproductive. Making language more specific and accurate improves communication, connection, and meaning. In the end, choosing to use hateful speech and defamatory language can have legal consequences.

Principles for using inclusive language every day

Toronto-based YouTuber, Kelly Kitagawa has shared some insightful observations about inclusive language that focuses on four main principles.5

1. Put the person first. Everyone is a person.

2. Respect self-identification. Use language consistent with someone’s identity. Pronouns are not preferred; they are just pronouns. Give the power to the people over their own stories and how they are described.

3. Proper nouns (names) help avoid stereotyping. They are also more specific.

4. Focus on the situation by using an active voice. It sets up your sentence to describe who is doing the action rather than what is being done to them. It’s a good way to identify and eliminate biases.

Making it easy for kids to learn inclusive language

Teaching children inclusive language at home helps them feel safe to develop their own unique identities, allows them to relate to their peers, and supports the development of that sense of belonging that is so fundamental to their health and happiness. Focus on modelling understanding and respect by making some simple language swaps.6

- Instead of husband/wife, say partner/spouse.

- Instead of girls/boys, say kids/everyone.

- Instead of ladies’/men’s room, say bathroom or washroom.

- Instead of brothers/sisters, say siblings.

- If you don’t know someone’s gender or pronouns, instead of saying his/her, say their.

Children, by nature, are inclusive and accepting. They are constantly learning about their world and environment that and almost nothing seems unimaginable or strange to them. You can read books that support diversity in family structures to help support their learning. Here are a few that you may want to explore with your children.

- The Great Big Book of Families by Mary Hoffman

- A Family is a Family is a Family by Sara O’Leary

- From the Stars in the Sky to the Fish in the Sea by Kai Cheng Thom

Finally, modelling inclusive language at home can help teenagers who struggle with creating and developing their own identities. Focus on creating a supportive and safe environment to incite further discussion about gender, sex, or sexual orientation. Take time to appreciate their interest in social causes, awareness, and activism by listening to them and encouraging respectful discussions.

Choosing inclusivity and belonging through language

You can demonstrate your commitment to fostering inclusivity and belonging by using inclusive language.

Here are seven tips to consider as you try:

- Don’t complain about it or express that you are struggling.

- Be respectful of the person and their situation.

For example:

• If you are speaking with someone who lives with a disability, “speak directly to them rather than through a companion, support person [or] interpreter.”

• Consider any extra time it might take for the person to speak.

• Avoid references that cause discomfort or are insulting.7 - Don’t over-apologize if you make a mistake. It will happen. Your apology forces the other person to discount their feelings to make you feel better.

- When someone corrects you, acknowledge them with thanks.

- Reinforce your learning when you need to make a correction by practicing the correct approach three times.

- If you observe a mistake, offer a quick correction. It helps the person become more aware, demonstrates respect and commitment, and shows empathy and understanding.

- Consider meeting up with someone else who is working on using inclusive language to practice.

References:

- Eisenberger N. I. (2012 January 27). The neural bases of social pain: evidence for shared representations with physical pain. Psychosomatic medicine, 74(2), 126–135. https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0b013e3182464dd1

- Cook, Gareth. (2013 October 22). Why We Are Wired to Connect. Scientific American. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/why-we-…

- Rinderle, Susana. (2018, March 28). Inclusion Doesn’t Mean Including Everything and Everyone. Workforce. https://workforce.com/news/inclusion-doesnt-mean-i…

- United Nations. (n.d.). Guidelines for gender-inclusive language in English. Gender-inclusive language. https://www.un.org/en/gender-inclusive-language/gu…

- Kitagawa, Kelly. (2021 March 25). Why inclusive language is so important! CBC Personal Politics. [YouTube} https://youtu.be/X3RRXoUnV3c

- Eng, Joanna. (2020 October 23). Simple Language Swaps To Make Your Family Vocab More LGBTQ-Inclusive. Parents Together. https://parents-together.org/simple-language-swaps…

- Humber College (2017). Inclusive Language in Media: A Canadian Style Guide. http://www.humber.ca/makingaccessiblemedia/modules…

Diversity And Inclusion: A Beginners Guide To The Holidays

Diversity And Inclusion: A Beginners Guide To The Holidays

Whether it has been the COVID-19 pandemic, social unrest, prejudicial injustice, environmental events such as fires and floods, or dramatic politics, 2020 has been a year of unique challenges and one for the record books, worldwide.We’ve seen and experienced social tensions unfolding in real-time with protests focused on supporting equality and justice for those oppressed and the illumination of the work that remains undone or the concerns not yet addressed. We need to appreciate our differences to find harmony in our workplaces and our communities. We can live more inclusively, value multiculturalism and recognize diversity.

With colder weather, seasonal changes, and less daylight, people are accustomed to getting together with friends, family and the community to celebrate traditions, religious beliefs, culture and history. The continuing pandemic will impose and alter how we typically share and experience these celebrations, however applying the necessary safeguards and taking the time to pause is worth the effort. During this time of year, festivals and holidays are filled with rituals and practices to honour heritage, raising our spirits to find optimism and hope for the coming days and year ahead. While there are many celebrations worldwide, taking time to learn about a few can enrich your understanding of the world and your community. We’re going to share a few that are celebrated between November and February each year.

Diwali

Diwali is a five-day festival for Hindu, Jain, or Sikh faiths that celebrates “new beginnings and the triumph of good over evil and lightness over darkness.”(1) In 2020, Diwali celebrations started on November 14th. The holiday is not fixed on the Gregorian calendar. Diwali can occur anywhere from late-October through to mid-November. While Diwali originated as a Hindu festival, it’s become a national festival in India that is enjoyed by non-Hindu communities as well. Each day of the festival focuses on a different ritual related to family and home.

Hanukkah

Hanukkah is an eight-day celebration in the Jewish faith known as the “Festival of Lights” or “Festival of Dedication.” Each year commemorates a 2200 year miracle where sacred oil that should have lasted only one day ended up lasting for eight. Hanukkah’s main ritual focusses on lighting the Hanukkah, a special candle holder with nine spots, two more than a menorah. (2) Families often celebrate with songs, prayers, games, foods fried in oil and gifts of coins. The dates for Hanukkah are not fixed. It can occur anywhere from late-November to late-December on the Gregorian calendar. This year, Hanukkah begins at sundown on December 10th.

Kwanzaa

Kwanzaa is a week-long celebration honouring African heritage focused on people, the struggle and the future. The holiday is defined by seven core principles: unity, self-determination, collective responsibility, cooperative economics, purpose, creativity and faith. Each day, a candle representing one of the seven principles is lit on a kinara, a seven-branched candelabra. (3) The holiday was started in 1966 and is observed from December 26 to January 1 each year. People often decorate their homes with colourful art and woven African cloth as part of the celebrations. A Kwanzaa feast on December 31st, known as the karamu, includes different ritualistic steps such as a welcome, remembrance, rejoicing and a farewell. On the last day of Kwanzaa, homemade gifts are exchanged.

Christmas Day and Boxing Day

Christmas Day and Boxing Day are national holidays in many countries that are observed on December 25th and 26th each year on the Gregorian calendar. Christians associate Christmas Day with the birth of Jesus. Boxing Day is a secular holiday. Decorations typically include displays of greenery, nativity scenes, emblems of winter (snowflakes and snowmen), and Christmas trees with lights and ornaments. Families and friends gather for meals and often exchange gifts. Orthodox Christmas, which occurs approximately two weeks later using the Julian calendar, falls in early January. People who observe this holiday participate in a period of fasting in the 40 days before where meat and sometimes fish must be excluded from diets. (4) Families and friends gather after mass to feast and celebrate the end of their fast. Traditional dishes are served that represent each of the apostles.

New Year Celebrations

While the Gregorian calendar is the most widely used in the world, many religions and cultures follow different schedules based on other calendars. They, therefore, have New Year celebrations that occur at different times of the year. We’ve focused on New Year festivals that occur during the Gregorian calendar months from November through February.

New Year’s Day, January 1st, is a national holiday that celebrates the start of the next year on the Gregorian Calendar. Before the end of New Year’s Eve, on December 31st, many people gather with friends and family to count down to midnight and welcome the new year and new beginnings.

Lunar New Year is a 15-day festival that marks the end of winter and transition to spring in Chinese culture. It falls at the end of January or mid-February on the lunisolar calendar. It is marked with celebrations and festivities meant to encourage good luck for the coming year. The holiday is also celebrated in Japan, Korea, Vietnam and Mongolia. Festivities celebrate ancestry, luck and good fortune with food, fireworks, parades and extended family gatherings.

Orthodox New Year falls mid-January aligned with the Julian calendar.

Tet Nguyen Dan or Tet is the Vietnamese Lunar New Year and the most important and popular holiday in Vietnam. Celebrations take place in late January or early February, and lead up to the first day of the Lunisolar calendar. People believe that what they do on the first day of the new year will “determine their fate” for the rest of the year. (5)

Looking for trusted resources?

You may be busy preparing to celebrate your festivities. It’s essential to recognize that not everyone in your workplace or circle of friends may be preparing for the same holiday. We shared a list of celebrations that typically occur during these months. It wasn’t exhaustive, and we did not include many details about these celebrations. In sharing them, though, we hope that we may have raised your curiosity. We hope you will consider others who are celebrating with their traditions and customs and have conversations with them to learn more. You can often find information about different events and cultural organizations that plan celebrations within the community to showcase holiday activities, sights, sounds and customs. Learning about holidays celebrated in different cultures can be a lot of fun and help people appreciate diversity.

At the same time, it’s also important to respect others who do not celebrate during this time of year. Focusing on understanding why people come together in harmony and celebration is an integral part of inclusive workplaces. We all have different viewpoints and are influenced by our cultural, religious and family traditions. Sharing insights with co-workers helps provide insight into how diverse our workplaces are. In the end, it helps us grow with pride, respect and diversity so that more knowledge is shared as we interact within our global population.

Finally, a reminder that if you will be gathering to celebrate and attend holiday festivals, it’s equally important to respect Public Health Guidelines in place for groups of people. Always be adaptable and willing to make modifications to help everyone stay safe. It is also a measure of respect for co-worker family members, and other citizens and something that should remain top-of-mind as we continue to live with COVID-19.

References

- Diversity Best Practices, (2019, November 21). Resources: 2020 Diversity Holidays. Retrieved on July 23, 2020 from https://www.diversitybestpractices.com/2020-diversity-holidays#november

- Weston, Tamara. (2011, December 20). Top 10 Things You Didn’t Know About Hanukkah: Eight Crazy Nights, The Hanukkah Menorah. Retrieved July 23, 2020 from http://content.time.com/time/specials/packages/article/0,28804,1947041_1947040_1947057,00.html

- Asemlash, Leah. (2019, December 26). The seven principles of Kwanzaa. Retrieved on July 23, 2020 from https://www.cnn.com/2019/12/26/us/kwanzaa-principles-trnd/index.html

- Cocullo, Jenna. (2018, January 7). Easter Orthodox faith community prepares to celebrate Christmas on Sunday. Retrieved July 23, 2020 from

- https://edmontonjournal.com/news/local-news/eastern-orthodox-faith-community-prepares-to-celebrate-christmas-on-sunday

- LaFairy (N.D.). All about traditions of Tet, the Vietnamese Lunar New Year. Retrieved on July 23, 2020 from http://www.lafairy-sails.com/en/blog/all-about-traditions-of-tet-the-vietnamese-lunar-new-year.htm

November 14, 2020