Celebrating Pride Means Supporting 2SLGBTQ+ Mental Health

Celebrating Pride Means Supporting 2SLGBTQ+ Mental Health

June is a time for celebrating the diversity of Canada’s 2SLGBTQ+ communities. But it’s also a time to reflect on how we can nurture and support that diversity every day of the year.

The 2SLGBTQ+ community is disproportionately affected by mental health and addiction issues, and it prevents many of its members from living their best lives and reaching their full potential. For families, friends, and caregivers alike, changing the way we think about 2SLGBTQ mental health and addiction treatment and recovery can transform the outcomes.

Progress and challenges

There is much to celebrate during this year’s Pride Month. As of 2023, Canada is home to one million individuals who identify as 2SLGBTQ+, which represents 4% of the total population aged 15 and older. Three-quarters of Canadians support same-sex marriage, and 61% say they support LGBT people being open about their sexual orientation and gender identity with everyone. Just last year, the federal government unveiled a five-year, $100 million plan to support 2SLGBTQ+ communities across the country.

Yet in some ways, 2SLGBTQ+ visibility and acceptance have never felt more fragile as there is often backlash. Between 2019 and 2021, hate crimes based on sexual orientation rose nearly 60% to reach their highest level in five years.

More than ever, we need to make an effort to understand, celebrate, and make room for queer lives and identities, and that’s especially true when it comes to supporting 2SLGBTQ+ mental health and addiction treatment.

The cost of being queer

The cost of being queer

In a perfect world, people of all genders and sexual orientations would be given equal opportunities to thrive. But the reality is that 2SLGBTQ+ Canadians still face multiple barriers to health, wealth, and wellbeing.

Many 2SLGBTQ+ Canadians live with the trauma caused by secrecy, stigma, discrimination, and fear. In addition to being the target of hate crimes, they are also more likely to experience financial distress, homelessness, and housing insecurity than heterosexual Canadians. Canadians who are 2SLGBTQ+ also have fewer job opportunities and earn significantly less than straight, male counterparts and experience frequent microaggressions at work. A lack of access to medical care, suboptimal healthcare experiences, and poorer health outcomes also diminish quality of life for queer people.

A mental health crisis

In the face of so many challenges, it’s unsurprising that the queer community sees a higher proportion of mental health and addiction issues.

Courtney Sullivan, Addiction and Mental Health Therapist and Support Coordinator at Homewood Health Centre, which is located in Guelph, Ontario and one of the largest mental health and addiction facilities in Canada, provides both outpatient and inpatient treatment for addiction and mental health. They work with clients who identify as queer, including individuals who may be experiencing homelessness, job loss, trauma, addiction, and a range of mental health issues.

“There is a lot of stigma towards the queer community,” they explained. “A lot of people have their families disown them or kick them out or withhold family support. A lot of queer youth, in particular, end up in the shelter system, which exposes them to trauma and substance use, and their mental health can get a lot more complex.”

Research shows that 2SLGBTQIA+ Canadians are seven times more likely to abuse drugs or other substances and five times more likely to have mental health issues. Sexual-minority Canadians are also approximately 25% more likely to contemplate suicide (40% vs. 15% for the general population) or have a mood or anxiety disorder (41% vs. 16%).

Treatment challenges

Not only do 2SLGBTQ+ have a higher likelihood of developing mental health issues and addictions, but their treatment journey is complicated by systemic ignorance and discrimination in the healthcare system.

According to a 2019 survey, 59% of nonbinary people were misgendered daily and only 47% felt comfortable discussing non-binary health concerns with their primary care provider. One in three said their primary healthcare provider had no knowledge about trans/non-binary health needs, and one in four did not have access to in-person spaces specific for non-binary people.

“There’s a large amount of queer people who don’t actually disclose their queerness to their health care providers,” said Sullivan. “The medical system doesn’t have the greatest history,” they continued, pointing out that as recently as the 1970s, homosexuality was classified as a mental disorder.

“People who do disclose to their doctors are often put in a position where they have to educate them about how healthcare should be delivered, which puts a huge burden on the queer community.”

It’s even more complicated for people with an intersectional identity that combines queerness with another identity that puts them at a systemic disadvantage, such as being a person of colour or an Indigenous person.

“Recovery programs and agencies and organizations really need to show their support to the queer community and signal that they are seen, that their experiences are respected, and that the facility is open to work with you,” Sullivan said.

While Sullivan advocates for big changes in the healthcare system, including hiring for diversity and developing organization-wide policies that reflect diverse perspectives, they also believe that small things can make a big difference. As an example, they described a recent situation when they brought a suicidal trans client who didn’t feel healthy at home to the hospital. Asking for help took tremendous courage, but the client was deadnamed three times in a row during the intake process, which almost made them reject treatment. (Deadnaming occurs when someone calls a transgender or non-binary person by the name they used before they transitioned. While deadnaming may be unintentional, it can feel stressful and traumatic because it questions or invalidates a person’s gender identity.)

“The hospital is supposed to be a healthy space, and most healthcare workers are well-intentioned, but systemic homophobia and racism can come out through the policies and the way things work,” they said. “Something as simple as restructuring medical charts so that gender information and preferred pronouns are easily available at a glance can change the experience. Or have care providers identify their pronouns, which is kind of like offering an invitation for that person to give you theirs too.”

S upporting 2SLGBTQ+ mental health

upporting 2SLGBTQ+ mental health

If you are a friend, partner, or family member of a 2SLGBTQ+ person exploring treatment options or actively in treatment or recovery, you can play an integral role in supporting their mental health and resilience.

For Sullivan, these communication tips can help to ensure they feel heard, seen, and supported throughout the journey.

Let them lead. “Your loved one might have a substance use issue, but if they’re not ready to hear it, don’t force it on them,” said Sullivan. “When people get scared, they make threats, like, ‘You need to get sober or else!’ But that ruins the opportunity and the trust.” Instead, let that person decide what they need and set the pace for treatment and recovery.

Keep an open mind. “Come at things with empathy and compassion. Listen to that person. Try to understand why they’re making the choices that they do.” Sullivan pointed out that for some members of the 2SLGBTQ+ community, the use of stimulants is an important part of their lifestyle and sexuality. “It all comes back down to the impact that the person’s substance use has on their life, and what that person identifies as being problematic.”

Respect their experience. “The trauma and the experiences that queer people have are different,” Sullivan explained. “Even if you’re cisgender and you get kicked out of your home, it’s still a different experience than someone being kicked out of their house because of who they are.” Respecting those differences can go a long way toward creating a space for authenticity and healing.

Pride in mental health

Pride in mental health

Pride Month is a time to celebrate the queer community and bring attention to the challenges it continues to face. The elevated risk of mental health and addiction issues is an important part of the story, and one that Homewood Health Centre and other mental health and addiction facilities in Canada are highlighting this year. We all have a role to play in supporting and protecting the mental health of 2SLGBTQ+ individuals, and that role goes beyond raising the rainbow flag.

“We’re having a flag-raising ceremony in honour of Pride here at Homewood, but that’s just the first step,” said Sullivan. “It’s about creating intersectional representation. You want people of colour working in your organization, you want Indigenous perspectives, you want queer perspectives. Be willing to hear the experiences of the people you employ and the people you support. Find out what it is that they’re looking for.”

Learn more about LGBTQ+ mental health.

Learn how to support children who identify as LGBTQ2+.

3 Ways Families can Support People in Addiction Recovery

3 Ways Families can Support People in Addiction Recovery

“While most of us have experienced some pain and anguish in our family, that family system can be a source of strength in healing from that pain.”

Dr. Julie Burbidge

Clinical Director, Homewood Ravensview

The negative impacts of addiction on families is well known. Less well known is the positive impact families can have on the addiction recovery journey. Parents, grandparents, spouses, siblings, and even children can play a powerful role in supporting a family member in addiction recovery and beyond.

In this blog post, we look at the difference families can make in the recovery journey and what they can do to support their loved ones as they transition from an inpatient treatment program to daily life.

Family support has a measurable impact

Supportive family dynamics can have a transformative impact. Family support can uplift every aspect of an individual’s life, from emotional wellbeing to physical health to academic and career success.

Even for an issue as complex and uncompromising as addiction, family support can make a measurable difference.

- A study of nearly 1,200 women who underwent inpatient treatment for substance abuse found that those with supportive families were less likely to relapse within six months of their discharge.

- A study of adolescents undergoing substance use treatment found that those who perceived their parents to be highly supportive had better outcomes than those who did not.

- A meta-analysis of 16 research studies found addiction treatments that involve family are associated with a 6% reduction in substance use compared to individual therapies.

- 65% of Canadians in treatment for an addiction said marital, family, or other relationships were the most important factor in initiating recovery.

Supporting a family member on the path to sobriety is no easy task, but the research is clear: family support can make a big difference.

“Positive attitudes and reinforcement from family members can inspire clients’ commitment to recovery,” explained Dr. Julie Burbidge, the Clinical Director at Homewood Ravensview, a private inpatient facility for mental health and addiction recovery in British Columbia. “It can also help them adapt to new challenges or limitations as they reintegrate with the wider world after spending time in treatment.”

Discharge is not the destination

When an individual completes a treatment program, it’s a major milestone and a cause for celebration, but it’s not the end of the road.

After the individual is discharged, the journey continues as they learn to resume their daily lives while remaining sober. The transition can be overwhelming, and it’s a time when family support in addiction recovery may be most needed.

While this transitional period is critical, it can be overlooked and under-resourced, which is why Homewood Clinics developed a series of post-discharge supports for patients and their families. Individuals who complete treatment are invited to participate in 12-month virtual support groups that meet weekly to focus on recovery management. For their families, an optional virtual meeting with a clinician is held each month at Homewood Ravensview. The facility is also launching a self-serve video hub where over 70 minutes of educational content covers a range of topics including talking to children about treatment, setting healthy boundaries, and understanding the stages of change in the journey to recovery. This will replace the virtual monthly meetings, and is meant to allow for more flexibility on when and how families receive these resources.

“Transitions are difficult because they involve uncertainty,” said Dr. Burbidge. “The more time and effort you put into planning for and discussing the transition plan, the more effective it will be.”

How to show your support

Supporting the recovery of an individual with an addiction isn’t easy, even for experts with years of specialized experience and training. For family members who don’t have that advantage, it’s even more intimidating.

Emotional dimensions can create further challenges. Even in families unaffected by addiction, relationships can be complicated. When addiction and mental health issues are added to the mix, the dynamics can be even more volatile.

“Being prepared for the transition home of a family member involves understanding your role in the recovery process,” said Dr. Burbidge. “It also means accepting that family life after treatment will be different and making a commitment to rebuilding relationships.”

Educating yourself ahead of time can help you prepare to provide family support in addiction recovery. Here are three of the most beneficial strategies for showing up in meaningful and constructive ways.

Understand the dynamics of change

People who undergo treatment for addiction are asked to change in profound ways, and that cycle of change doesn’t stop when they are discharged.

“Sometimes family members have the misperception that their loved one will be ‘fixed’ or ‘healed’ when they leave treatment,” Dr. Burbidge explained. “Treatment is an important step in a person’s healing and recovery, but the process continues long after their discharge.”

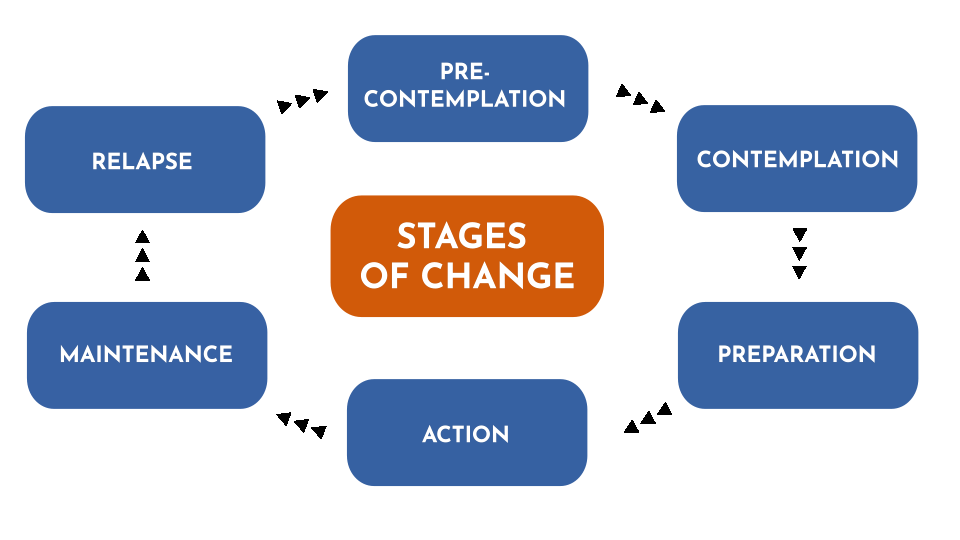

Understanding the stages of change can help family members recognize, accept, and meet people where they are in the journey.

The most important thing to understand about the path to change is that it isn’t tidy and linear. Just as a person with diabetes or asthma can relapse after being released from treatment, a person in addiction recovery may experience a relapse as they work toward sustained change. A relapse shouldn’t be seen as a failure but as one stage among many in the recovery process.

Stages of Change

As people pursue their recovery, they cycle through various stages that can involve new thoughts, attitudes, and behaviours. Every journey is different, and few journeys are perfectly linear. This diagram represents the change model used by Homewood Ravensview, a private inpatient facility for mental health and addiction recovery in British Columbia.

There are several ways you can help to prevent or mitigate the impact of a relapse:

- Talk to the person in recovery about relapse so they know you understand it’s something that might happen.

- Let them know that you are there to support them and ask if they would like you to play a role in their relapse prevention plan.

- Pay attention to your own behaviours. Families can sometimes fall back into old, destructive patterns.

Learn to communicate effectively

Effective communication is the key to healthy interpersonal relationships, but it’s easy to slide into defensiveness and blame during times of stress and anxiety.

Dr. Burbidge advises family members to try using a form of assertive communication called “‘I’ statements” to create a connection with the person they’re speaking to and avoid slipping into harmful communication patterns that rely on accusing, blaming, and shaming. ‘I’ statements focus on your own experience and how you feel about it rather than focusing on what you think the other person is doing wrong.

“This gives us a way to express our feelings in a manner that is respectful and increases the likelihood that the other person will be open to hearing what we have to say,” said Dr. Burbidge.

You can express yourself with ‘I’ statements using a simple formula: “I feel [describe your feeling] when you [describe the person’s actions] because [describe the reason it makes you feel a certain way].

Here’s an example:

| Conventional ‘you’ statement | ‘I’ statement |

|

“You never listen to me. You make me so angry because you just don’t care enough about me to bother to listen when I’m trying to talk.”

|

“I feel angry when you interrupt me because It’s important to me that I’m able to share my ideas with you and feel heard by you.”

|

Set and respect boundaries

During treatment for addiction, people learn how to create boundaries as a way of staying on the path toward healing. As the family member of a person in recovery, you can support them by recognizing and respecting those boundaries. Setting boundaries of your own can also be very helpful in allowing you to preserve your energies and self-respect as you explore new ways of relating to that person.

“Boundaries are a way to establish where you end and other people or external influences begin,” explained Dr. Burbidge. “They are a way of setting healthy limits around what we will and won’t accept or do in our relationships with others.”

To set a healthy boundary with someone:

- Describe the boundary you are setting or the action that is causing you discomfort.

- Express how the situation makes you feel using ‘I’ statements.

- Describe the behavioural change you are looking for in the future.

- Without making threats, describe the action you will take if your boundary is crossed.

Here is an example:

“I feel angry when you interrupt me because It’s important to me that I’m able to share my ideas with you and feel heard by you. Moving forward, I would like it if we could each take turns speaking. This will help us better understand each other and hopefully feel more connected. The next time you interrupt me, I will leave the room and we can continue the conversation later.”

Take the next step together

An individual who has completed an inpatient addiction treatment program has done some hard and courageous work toward furthering their recovery. Re-entering their normal lives post-treatment is the next big step in their journey. By understanding the stages of that journey and learning new ways of communicating and interacting along the way, families can make a positive difference in the individual’s recovery experience and outcomes.

“To truly understand the individual, we have to understand the family system of that individual,” Dr. Burbidge said. “While most of us have experienced some pain and anguish in our family, that family system can be a source of strength in healing from that pain.”

For more insight into supporting a family member in addiction recovery, read these articles from Homewood Ravensview, an addiction treatment program in British Columbia, Canada.

Understanding Family Dynamics: What healthy family traits look like, and how to identify toxic family dynamics.

Supporting Those with Addiction: How to support family members who haven’t reached out for help yet.

Top 5 Tips to Motivate Someone with an Addiction, Towards Treatment

Top 5 Tips to Motivate Someone with an Addiction, Towards Treatment

1. Empathize, don’t criticize. Every time you point a finger, you could be pushing your loved one farther away. Ask questions and listen.There is great power in a supportive loved one communicating with empathy and without judgement.

2. Be firm but fair. Specify some ground rules. Make it clear to them that you will not support their addictive behaviour, and try to set healthy boundaries. With these boundaries in place, they may just be motivated enough to start thinking about quitting.

3. Tell them how you feel. Sometimes, a person living with addiction may not realize how their behaviour has affected you and others in their life. Don’t be afraid to share your feelings with them; doing so could show a significant level of care and support.

4. Use “I” statements. As you express your emotions to your loved one, make sure not to point fingers or fault toward them. They already suffer from their own guilt and shame, so you may risk them shutting down completely. Rather than passing blame and telling them what they did, turn it back around to you. Making statements using “I feel” instead of “you” can help promote healthy communication.

5. Address their fears. A huge factor in resisting treatment is fear of the unknown. Hop onto our site and educate yourself. Knowledge is power when it’s time to have that conversation.

Coping with Childhood Trauma from Past Abuse and Neglect

Coping with Childhood Trauma from Past Abuse and Neglect

In this article, we’ll be exploring the topic of past childhood trauma. While we always intend to be helpful when presenting information, we only encourage you to proceed if you recognize how this could affect you. Only you know best if it’s something you want to continue with. Please remember that if you have experienced past childhood trauma personally, we want to encourage you to take breaks while reading, especially if you are feeling uncomfortable or strongly react to what we’re sharing. We’ve included some resources near the end of the article that you may want to consult.

Many of us have experienced challenging moments in our lives. Memories of past childhood trauma may not be immediately obvious or apparent. They are often repressed in our minds or we may make a conscious effort to avoid thinking about these memories because they cause such a strong emotional response in us. While scientists are still researching and determining the complexity of connections between traumatic experiences and memories, “experts in child psychology argue that the memories formed from infancy to the age of 2 or 3 are very unlikely to be recovered.” (1)

We will look at how to recognize childhood trauma, find out how commonplace it is, and learn about some of the trauma people might have experienced that they have held on to and how it is affecting their adult lives. Then, we will talk about how repressed trauma may appear in adulthood and what our reactions to discovering it might involve. It’s important to understand that trauma is unresolved stress and does not become your identity. With the right understanding, practical coping tools, and a framework resolution, you can move forward and heal from these events to live well and feel better.

What is childhood trauma?

Childhood trauma is stressful experiences, such as abuse, neglect and household dysfunction, that occur before age 18. Traumatic experiences usually involve situations where children feel threatened either physically, emotionally or both. Trauma is highly individualized because not everyone is affected by the same things or in the same ways. That makes it quite challenging to determine the exact causes. However, studies show that childhood trauma can affect a person’s mental and physical health over time because our memories store both the events and the associated feelings/reactions.

What is a trigger for negative reactions?

When we don’t have an immediate frame of reference for something, our brains (whose primary purpose is to help us survive) may turn to memories of traumatic events. It can create an unexpected reaction. What’s happening is that we haven’t found a way to process and let go of the associated trauma. Our bodies, in turn, respond in several different ways:

- nightmares

- flashbacks

- confusion

- sleep disorders

- anxiety and panic attacks

- depression

- grief

- guilt

- shame

- nervousness in everyday situations

Attempts to try to address the trauma may lead to behaviours that are associated with a range of mental health conditions that could include:

- substance use

- self-harm

- eating disorders

- personality

- mood disorders

How common is childhood trauma, and how often does it occur? Are certain groups or people affected more than others?

Dr. Gabor Maté is a physician who has studied trauma’s connection to our health in a biopsychosocial context – how our health is affected by events we have experienced throughout our lives. He asserts that we need to acknowledge trauma because the interconnectivity between our psychology and physiology cannot be denied. (2)

Historically and currently, childhood abuse and neglect are often underreported for many different reasons ranging from children being generally unaware that what is happening to them is wrong, to being afraid to tell someone they trust what is going on. (3) In 2014, a General Social Survey conducted in Canada included questions about “maltreatment during childhood” for anyone over 15 to answer. It was ground-breaking because this study was the first-time data about childhood trauma and abuse had been collected nationally from adults. Here are some of the results: (4)

a.Those between the ages of 35 and 64 years of age at the time of the survey were the most common segment reporting abuse.

b.33% experienced physical or sexual abuse by someone over 18 or witnessed violence between known adults.

- More males (27%) than females (19%) experienced it and were almost twice as likely to report it. However, females were 3x more likely to have experienced sexual abuse before age 15.

- 65% of abused people reported occurrences between 1 and 6 times; 20% reported being abused between 7 and 21 times; and 15% reported abuse of at least 22 times,

- For 61% of respondents, parents and step-parents were responsible for the most severe physical abuse; but sexual abuse most often happened by someone outside of the family.

- 67% of victims never told anyone about the abuse.

c.40% of Indigenous people have experienced abuse compared to 29% of non-indigenous, and 42% of indigenous women have, compared to 27% of non-indigenous women.

d.48% of respondents who identified as members of the LGBTQ2 community reported having experienced abuse compared to 30% of heterosexuals.

e.Immigrants were less likely than non-immigrants to report a history of abuse as children. When abuse occurred, someone outside their family most often perpetrated it.

f.Drug and alcohol use were twice as common for people who had experienced childhood abuse.

g.There were negligible differences between people who had experienced childhood abuse when it came to education, employment, or income as adults.

Types of trauma

There are many different types of trauma that people have experienced.

Neglect

Neglect is where a child’s or teen’s needs are not attended to, exploited, pushed aside, or greatly resented. It can have immediate, short-term, and long-term consequences.

Neglect can be considered a general unawareness or systematic failure of a caregiver to respond to a child’s needs because they were overwhelmed or preoccupied. It’s often unintentional, perhaps reflecting low awareness and emotional intelligence or even a remnant of intergeneration trauma. In some instances, basic needs could be provided by caregivers, but it’s the emotional and psychological needs that are not. Sometimes it’s a case of caregivers “mishand[ling] one key area of support.” (5) For example, a child could be experiencing a lack of:

- comfort

- nourishment

- shelter

- medical care

- emotional support

- education

- caregiving (leaving a child alone or in the care of a third party who cannot provide adequate care)

- general resources such as food and clothing or even love when they are part of a large family

Neglect can be a “failure to act or notice a child’s emotional needs,” which results in chronic emotional and psychological crises that can affect brain development. (6)

From the caregiver’s behaviour, a child learns that their needs are unimportant and that seeking adult support is often futile. In households with strict rules – such as no crying, no sadness, or no loud voices – the adults discourage natural, spontaneous responses from the child or teen. Instead, they should acknowledge that the child is likely instinctively expressing a need to feel close and share their emotions. By denying them the opportunity to process their feelings, these children grow up learning that mentioning these natural responses is something to fear. In the child’s adult relationships, this can manifest as mental and physical difficulties where they:

- feel low self-worth

- have low self-esteem

- display low confidence

- have trouble with loneliness

- are focused on perfectionism or avoidance, and

- find comfort in self-deprecation

Children also learn from caregiver behaviours such as being emotionally detached, anxious, or constantly worried.

Abuse

Abuse can be viewed as an intentional, conscious action or decision by a caregiver to deny a child care or harm them. In many circumstances, the abuse is physical or sexual. The abuse creates trauma.

Children who have experienced neglect and abuse are vulnerable to other traumatic events that are offshoots of the original trauma. It could be that they are threatened by, become involved in, or witness an event such as (7):

- bullying

- community violence

- multiple complex traumatic events

- natural disasters

- early childhood trauma that occurs before age 6

- intimate partner violence

- traumatic medical stress

- refugee trauma

- traumatic grief such as the loss of a parent or close caregiver, or family member

- the end of a relationship (divorce)

- having a learning disability

- having a caregiver with untreated mental illness

Recognizing the signs of unresolved trauma

Symptoms of unresolved trauma start when adults experience stress or when experiences remind us about something that happened when we were children. Adults who have experienced childhood trauma aren’t always able to recognize their own trauma because they have usually developed strong self-reliance and have often been the ones to build a solution to cope with these experiences independently.

As a result, it may be challenging to consider that symptoms of unresolved trauma may look like somewhat ordinary things. But these are often the body and mind’s ways of alerting us to problems that originated in childhood:

- Chronic pain – migraines, joint and nerve pain, back pain, fibromyalgia, etc.

- Fatigue – constant low energy, weakness, brain fog, sleepiness, etc.

- Digestive issues – nausea, diarrhea, constipation, IBS, etc.

- Hypersensitivity/Hypervigilance – awareness of sensations to sounds, lights, environments, etc.

- Anxiousness – increased heart rate, panic disorders, fears, etc.

- Depression – low moods, lacking motivation, feeling hopeless, etc.

Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE)

Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) is “used to describe all types of abuse, neglect, and other potentially traumatic experiences that occur to people under the age of 18 years.” (8) ACE scoring is a methodology to help adults reflect on situations that may have affected their development. ACEs have the potential to uncover symptoms of childhood trauma because an adult can better articulate whether they feel they’ve been able to deal effectively with the ACE. In fact, “one in every six adults experience at least four ACEs, according to the CDC. These experiences can be particularly harmful because they occur at such a vulnerable phase of growth. In early childhood, brain development and social-emotional growth are at a critical stage.” (9)

How to recognize if childhood trauma is affecting you as an adult

It’s important to realize that not all trauma is due to mistreatment or abuse. Children can experience frightening events in their lives, such as accidentally getting separated from their caregiver in a store or being startled and uncomfortable because of loud noises in their environment. They can also experience trauma when they experience something new or, for the first time, like visiting a doctor or dentist. These events can create memories associated with trauma, but the cause was not neglect or abuse.

Some professionals help people sort through types of traumas by helping determine whether they have experienced what they are referring to as Big T Trauma or Little t Trauma, which attempts to explore them in the context of how the event affected someone’s physical safety to produce the traumatic response. This approach can help someone determine if these experiences are affecting our innate sympathetic nervous reactions, also known as fight, flight and freeze.

Big T traumas are “generally related to a life-threatening event or situation…[like] a natural disaster, a violent crime, a school shooting, or a serious car accident,” but “chronic (ongoing) trauma, such as repeated abuse, can also qualify as big T trauma.” (10)

Little t traumas are “events that typically don’t involve violence or disaster but do create significant distress… [such as] a breakup, death of a pet, losing a job, getting bullied, being rejected by a friend group.” (11)

Common reactions to trauma

Framing childhood trauma may be difficult because we tend to discount the impact of events that happened to us in childhood. After all, they happened at a time in our lives when we didn’t have the evaluative tools, control, and self-determination that adults do to process situations.

Our adult perspective and viewpoints can also cloud or invalidate the child’s reaction to the trauma. For example, uncharacteristic responses from adult figures that may have been frightening to you as a child and perceived as threatening may not be viewed the same way today. There’s also a tendency to internalize responsibility for the caregiver’s actions, taking on blame for a situation and excusing the caregiver. It can be because, as a child, you were told you were responsible for that adult’s behavioural choices at the time.

Many adults also experience disassociations where they strategically avoid certain situations. Generally, it’s because they cause them discomfort as adults. An example of disassociation would be how as an adult, you can never be late, or it can cause you to panic. The root cause may be a childhood experience where a caregiver was late to pick you up. The emotions that the event made you feel may have influenced your development so that you unknowingly relive an unresolved traumatic experience from your childhood.

Ways to heal from childhood trauma

Now that we have looked at what trauma is, and unveiled how people may have experienced trauma, as well as abuse, it is time to look at ways which we can heal from childhood trauma. The following gives some strategies for healing.

- Learn to approach memories calmly and recognize and be curious about our automatic reactions. It is fundamental to learning about what triggers us, which can help process those triggers, removing their intensity over time.

- Try to fill in the blanks/gaps in memories by approaching them with storytelling. This method can help gently bring memories forward because it allows us to be more mindful as adults. We can leverage more emotional regulation tools that we have learned to understand these situations and process the experiences from a different perspective. It also helps us release the fearful associations and acknowledge how we can choose to remove the trauma, so it doesn’t continue to have a hold on our current lives.

- Explore a wide range of treatment options:

- CBT – cognitive behavioural therapy helps people re-think their thoughts and beliefs about traumatic events and activate healthy coping skills.

- DBT – dialectical behavioural therapy helps to build skills in responding to stressors and emotional regulation.

- EMDR – eye movement desensitization and reprocessing helps retrain areas of the brain that hold traumatic experiences by following a series of specific eye movements performed under the direction and guidance of an EMDR therapist.

- Somatic Experiencing (or similar types of therapy) – create positive mind/body connections that help reset the nervous system. These could include treatments such as:

– Meditation

– Deep breathing

– Yoga

- Clinical EFT (Emotional Freedom Technique) focuses on stimulating acupressure points in the body with a repeated light touch.

- Clinical Myofascial Release focuses on specific guided motions to expand and contract tissues that relax and release tension and trauma.

Childhood trauma resources

You may want to review some of the most innovative thinking about childhood trauma from people who have extensively studied links between it and health as adults. They advocate for different approaches for physicians to acknowledge and address trauma’s effects on our lives.

- Dr. Gabor Maté has written several books on the topic, including the recent release “The Return to Ourselves: Trauma, Healing and the Myth of Normal”

- Dr. Bessel van der Kolk created the National Child Traumatic Stress Network https://www.nctsn.org and has published a book about trauma titled “The Body Keeps the Score”

- Dr. Nadine Burke Harris gave a TED talk: “How childhood trauma affects health across a lifetime, “where she discussed studies prepared by the Centres for Disease Control (CDC) and Kaiser Permanente. She has published a book titled, “The Deepest Well: Healing the Long-Term Effects of Childhood Adversity”

We have also included links to some Adverse Child Experience (ACE) Questionnaires that you may be able to explore as you begin working on healing from childhood trauma.

- ACE Questionnaire from The Canadian Association for Mental Health, CAMH.

- Finding your ACE score from the National Centre for Juvenile Justice, Family Violence and Domestic Relations, and Child Welfare and Juvenile Law NCJFCJ

Above all, please be gentle with yourself as you explore your childhood trauma. It can be a difficult, lengthy, and complicated process to work through as an adult, and you may find that you are not ready to talk about it. Remember that you don’t need to figure everything out alone. Taking time and space to heal is one of the most significant gifts you can give yourself.

References:

1. Positive Kids n.d). The Child Psychology of Abuse and Repressed Memories. PositiveKids.ca. Retrieved February 10, 2023 from https://positivekids.ca/2017/01/09/the-child-psych…

2. Maté, G. (2023 February 22). George Stroumboulopoulos in conversation with Dr. Gabor Maté Live on Instagram. Instagram @strombo, @gabormatemd.

3. Burczycka, M. (n.d.). Family Violence in Canada: A statistical profile, 2015, Section 1: Profile of Canadian adults who experienced childhood maltreatment. Statistics Canada. Retrieved February 10, 2023 from https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/85-002-x/20170…

4. Ibid.

5. Holland, K. (Medically reviewed by Legg, T.J., PhD, PsyD.) (2021 October 21). Childhood Emotional Neglect: How It Can Impact You Now and Later. Healthline.com. Retrieved February 10, 2023 from https://www.healthline.com/health/mental-health/ch…

6.Ibid.

7. The National Child Traumatic Stress Network. (n.d.). What is childhood trauma? Trauma Types. The National Child Traumatic Stress Network (NCTSN.org). Retrieved on February 10, 2023 from https://www.nctsn.org/what-is-child-trauma/trauma-…

8. Su, Wei-May & Stone, Louise. (2020 July). Adult survivors of childhood trauma: Complex trauma, complex needs. Australian Journal of General Practice (AJGP). Volume 49, Issue 7. Retrieved on February 10, 2023 from https://www1.racgp.org.au/ajgp/2020/july/adult-sur…

9. Newport Institute. (n.d). Big T vs. Little t Trauma in Young Adults: Is There a Difference? Newport Institute.com. Retrieved on February 10, 2023 from https://www.newportinstitute.com/resources/mental-…

10. Ibid.

11. Ibid.

It's not Just you. The Post-Pandemic Workplace is Stressful for Everyone

It's not Just you. The Post-Pandemic Workplace is Stressful for Everyone

Whether it takes place at home, in an office, or out on the front lines, work can be a stressful experience. In fact, Canadian workers are among the most stressed in the world.

“A lot of people don’t even realize they are experiencing moral distress. They have this general sense of outrage at the system and don’t see it for what it is.”

Work-related stress existed long before the pandemic, but it rose to new heights as our workplace fundamentals changed overnight. While the terrifying uncertainty of the early pandemic is now far behind us, the aftershocks continue to impact our mental wellbeing.

A Capterra survey found that while the percentage of Canadian employees reporting negative mental health quadrupled during the pandemic, that percentage hadn’t diminished in 2022. In fact, it had increased very slightly.

A 2022 Gallup report found that Canada is one of the most stressed regions of the world. In 2022, 44% of employees saying they experienced stress a lot of the previous day—the highest percentage in a decade.

Workers of all types are feeling stressed

Whether you perform your job remotely, on site, or on the front lines, you may be feeling work-related stress.

Nearly one in five workers in Canada are now fully remote, and while many people enjoy this work style, for others, it has created feelings of isolation and blurred the boundaries between work and life in an unhealthy way. A 2022 survey by Cisco found that stress levels had increased for more than one in five remote or hybrid workers (22%).

Many on-site workers are also struggling for reasons that include health concerns and badly-behaved customers. According to Capterra, nearly one-quarter of on-site workers (24%) rated their mental health as “bad” or “very bad.”

But first responders—the people whose work puts them in emergency situations regularly—experience some of the highest levels of work-related stress.

Alexis Winter, former Director of Nursing at Homewood Ravensview, a Canadian private mental health and addiction inpatient treatment facility on Vancouver Island, British Columbia, works with many first responders through the facility’s Guardians Program.

She agreed that the pandemic and its aftermath have worsened the mental health of front-line workers of all types.

“They’re putting their bodies on the line, and that the general population wasn’t supporting them,” Winter explained. “Health care staff were putting themselves in dangerous situations and feeling villainized. They were feeling like, ‘We don’t matter.'”

The phenomenon is directly correlated with more acute conditions such as burnout and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), said Winter. Unfortunately, it’s all too easy for people to ignore the symptoms.

“A lot of people don’t even realize they are experiencing moral distress. They have this general sense of outrage at the system and don’t see it for what it is.”

The impact of work-related stress

Stress is a natural reaction to situations that seem overwhelming or threatening, priming our bodies to release stress hormones that trigger a “fight or flight” response that can protect us from danger. In a workplace setting, these situations can include physically unsafe environments, discrimination, bullying, unrealistic workloads, financial uncertainty, lack of autonomy—the list goes on and on.

But when we experience repeated exposure to these triggers over time, stress stops having a beneficial effect and starts adversely affecting our mental and physical health. In addition to anxiety, burnout, depression, and PTSD, stress can cause hair loss, memory loss, acne, hives, ulcers, heart disease, hypertension, acid reflux, headaches, insomnia, fertility issues, sexual dysfunction, obesity, and increased consumption of drugs and alcohol.

Many first responders are at elevated risk of mental health issues related to their work.

69% of Canadian journalists and media workers suffer from anxiety and 53% have sought medical help to deal with work stress and mental health.

48% of Canadian nurses say the pandemic affected their work-life balance to a great extent and 50% experienced abuse by clients or the public at work.

53% of Canadian physicians report symptoms of burnout in 2022—1.7 times higher than the pre-pandemic number.

50% of Canadian police officers reported having high levels of perceived stress.

86% of firefighters in the Northwestern Ontario fire service experienced symptoms of PTSD.

Recognizing the problem

Being able to recognize when stress is becoming harmful is critical to mental health.

People usually know when they’re stressed at work, but many see it as a normal part of having a job. If you find yourself dreading work or feeling hopeless and helpless on a regular basis, it’s a sign that your work stress may be rising to unhealthy levels.

“It’s about self-awareness,” Winter explained. “Noticing whether you’re feeling really tired, whether you’re feeling negative toward things you used to believe in. How do you feel after taking a break? Do you come back feeling good and ready to work? If you don’t feel that sense of regeneration after time away from work, it’s a sign that stress has become trauma or moral distress.”

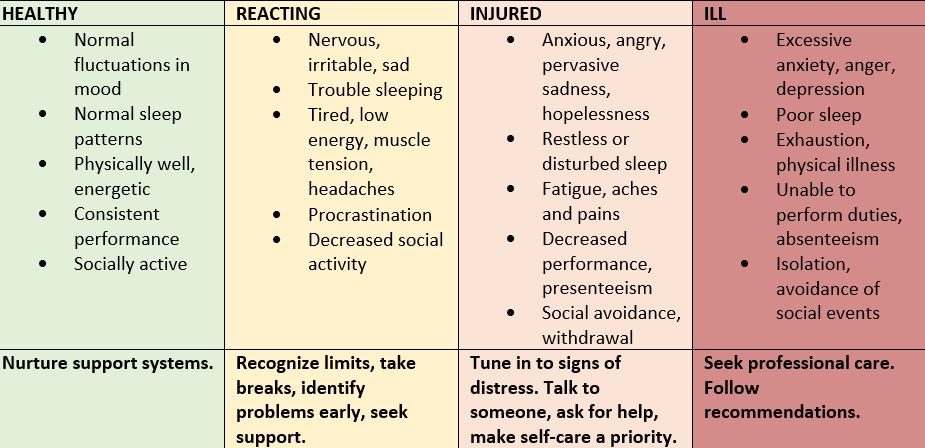

The continuum model provided by the Mental Health Commission of Canada is a helpful tool for understanding mental health as a continuum and gauging the severity of a person’s reactions to workplace stress. By evaluating yourself against each point in the continuum, you can gain a better understanding of your mental health and your potential need for lifestyle changes or professional help.

Coping with work-related stress

If your work-related stress levels are rising, there are things you can do to manage them. Here are some of the self-care strategies recommended by the team at Homewood.

Recharge. Take regular and assigned breaks at work. Take your vacation days, avoid working unnecessary overtime, and focus on rest and recovery whenever possible.

Prioritize. Know your limits. Create a routine for creating a boundary between work and the rest of your life. Make exercise, proper nutrition, and adequate sleep a priority.

Organize. Create a work environment that is tidy and organized. Break down seemingly overwhelming projects into smaller, achievable tasks.

Celebrate. Recognize and celebrate your successes (big and small) and try to keep your self-critic in check.

Connect. Seek the support of your team members or leader, and access organizational supports, such as health and counselling resources.

Winter also offers these coping mechanisms from her own practice.

Avoid relying on drugs and alcohol. “If you come home feeling really stressed out about work, don’t reach for a glass of wine or a beer immediately. Even if you only have a single glass each evening, try bringing yourself down in other ways so that using these substances doesn’t become a habit.”

Adopt a mindfulness practice. “If you’re experiencing depression, you’re living your life in the past. If you’re experiencing anxiety, you’re living your life in the future. A daily mindfulness practice, even 10 minutes before bed, helps you bring yourself into the present and alleviate those symptoms of depression and anxiety.”

Create better boundaries. “Something as simple as turning your phone off when you leave work can make a huge difference, because even that five-minute check is actually taking up 20% of your brain space for the next little while. I now have a separate work phone and a personal phone.”

Ask for help. “If you’ve taken some time away from work and you’re still feeling burned out, or if your beliefs about the safety of the world or the goodness of people has changed, it’s time to go beyond self-care and start asking for help.”

An experience we all share

Many of us are lucky enough to earn a sense of purpose from our work as well as a pay cheque. But with so much of our time and identity tied up in work activities, it’s easy for work to become a source of significant stress, and the pandemic only intensified the phenomenon. Whether we work from home, in an office, or on the front lines, it’s not uncommon for the daily grind to grind down our mental health.

What’s important is to recognize when our stress levels creep up so that we can take action, whether that involves rebalancing our work-life focus, practicing better self-care, or reaching out to people who can help us heal.

Tuning In: The Role of Music Therapy in Mental Health and Addiction Treatment

Tuning In: The Role of Music Therapy in Mental Health and Addiction Treatment

Kirsten Davis, a music therapist at Homewood Ravensview, a private inpatient facility for mental health and addiction recovery in British Columbia, sits in front of a piano with her patient. The woman is terrified, her body tense, her fingers reluctant to so much as touch the keys. Gradually, Davis encourages her to play a chord. Then another. And another. What happened next is a testament to the extraordinary healing power of music.

“She started to relax,” Davis recalls. “Together, we played, and she started to laugh and do silly things on the piano, like playing it with her elbows.”

Goofing off at the piano may not seem like much of breakthrough, but Davis’s patient was a residential school survivor who was struck by the nuns who taught her every time she played the wrong note. Traumatized, she had not touched a piano since. But at Ravensview, she was finally ready to face her fears and find her voice.

“At the end of the session, she discovered that the piano was not this scary monster anymore,” says Davis. “It was something that could be fun and joyful.”

The healing power of music

Humans have instinctually recognized the power of music for centuries. In ancient Greece, music’s effect on the mind and body was considered so intense that some believed it should be controlled. In ancient Egypt, physicians used music to help patients recover from illness. And in many Aboriginal cultures, music is viewed as a powerful healing tool.

Today, music is globally recognized as a therapeutic intervention in a wide variety of clinical contexts. To date, more than 1,000 scientific studies have been published on the topic of music therapy and its impact on everything from asthma management to autism to pre-term infant care to palliative pain relief. Music therapy has also become a vital component in mental health and addiction treatment options for conditions such as anxiety, depression, dementia, stress, PTSD, and addiction to alcohol, drugs, or prescription medications.

In this article, we’ll look at how music is being integrated into holistic treatment programs in Canada to help people identify, explore, and regulate their emotions to discover new resilience, confidence, and authenticity.

What is music therapy?

Music therapy uses music as a therapeutic tool to address emotional, cognitive, social, and physical needs of individuals. It is delivered by a trained and licensed therapist who uses music to help people achieve therapeutic goals, such as improving communication and expressive skills, managing stress, and enhancing overall well-being.

Music therapy can involve a wide array of activities, including group drumming sessions, learning to play an instrument such as the guitar or piano, singing and breathwork, sharing and analyzing songs, creating new music, lyrics, or soundscapes individually or as a group, or simply listening to music for relaxation or emotional discovery.

Davis believes that music therapy provides an important outlet.

“There’s so much work that we do in treatment that’s based on talking,” she says. “If we can provide ways for people to express themselves without using words, that’s really important.”

Priya Shah, who provides music therapy at Homewood Health Centre, an inpatient treatment facility in Guelph, Ontario, sees music as a way to explore difficult emotions or experiences safely.

“Music can act as a form of symbolic distance,” she explains. “Someone can say they relate to a specific song or lyrics without actually saying, ‘This is what happened to me,’ or ‘This is how I’m feeling.’”

Who benefits from music therapy?

As part of mental health and addiction treatment services, music therapy benefits a wide range of individuals as part of a holistic treatment approach. At Homewood Health facilities, music therapists collaborate with other expressive arts therapists (art, creative writing, and horticulture), cognitive behavioural and dialectical behavioural therapists, physicians, and nurses to develop programs for:

- People with acute or life-threatening psychiatric conditions or addictions

- People who have been diagnosed with depression, bipolar disorder, or anxiety disorders such as generalized anxiety disorder, social anxiety disorder, panic disorder, or agoraphobia

- First responders, including firefighters, paramedics, law enforcement, military personnel, and veterans, who have post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) or occupational stress disorder (OSI)

- People with neurocognitive impairment or forms of dementia including Alzheimer’s

- Youth in their teens to early 20s with mental health or addiction issues or a history of trauma and secondary diagnoses such as eating disorders or self-harm

How music therapy supports recovery

Shah and Davis both describe music as a versatile medium that can promote the emotional wellbeing of people undergoing mental health and addiction treatment by helping them to connect with, understand, and share their emotions in a safe and creative environment.

Connecting with emotion

Shah says that people often come to music therapy with a certain emotion in mind that they’d like to evoke through music. With the help of a trained music therapist, they can get in touch with those sometimes-overwhelming emotions in a safe space.

“Sometimes patients come to a group saying, ‘I want to release some anger,’ or, ‘I want to cry,’” says Shah. “There can be moments that feel uncomfortable, messy, and chaotic, but music can act as a form of symbolic distance. In individual or group sessions, we practice using music to build distress tolerance.”

Understanding emotion

Being able to name, understand, and accept the emotions they feel also plays an important role in a person’s recovery, and it’s a skill many people in recovery have difficulty with.

“Music can help people identify and express emotions,” Davis says. “We’ll sometimes listen to a song and pull it apart to understand what mood it’s expressing and why people are connecting with that.”

Sharing emotion

Music can also be used to bring people together and help them understand and accept one another and themselves. By sharing a favourite song or lyric with a group, or by creating music and sounds that express their feelings and experiences, people can learn to connect with others and build relationships of trust.

“A lot of the benefit comes from relating to peers and connecting with people who have had similar experiences,” Davis explains. “People find such comfort in realizing they’re not alone, that there are other people who have had those kinds of experiences.”

Creating a safe space

People receiving treatment for mental health and addiction issues face intense psychological challenges, and the emotions and experiences that music evokes can be overwhelming if they are not explored with the help of a trained therapist.

To help their patients safely explore and gain control over the intense emotions that can come up during a therapy session, Shah and Davis ensure that every session is personalized, structured, and nonjudgmental.

Personalized

Shah never sets a routine or schedule. Instead, she checks in with the individual or group to assess what’s needed in the moment and that sets the direction for the session. Activities can include listening to music, singing, playing instruments, creating music or soundscapes, writing lyrics, analyzing or talking about a piece of music, or even dancing.

Davis also takes care to customize the music selection to reflect participants’ tastes. For example, for the “My Path” mental health treatment program for youth at Ravensview, the music selection leans toward hip-hop, rap, and pop.

“For young people, research shows that music is very connected to identity development,” says Davis. “It can help them get in touch with their angst and anger at a safe distance and sharing that music with peers can really validate their experience.”

Structured

Despite being flexible in her approach, Shah believes in carefully structuring therapy sessions so that participants can be playful and experiment, but also have a framework to guide them if they need it.

“Creating sound isn’t always harmonic or pretty. Building comfort with those messy parts of music is an important part of the process,” Shah says. “There can be a lot of perfectionism and fear of getting things wrong. Having something structured can give people something to hold on to, some comfort and instruction. Part of my job is knowing when to challenge and when to let music be a safe place.”

Nonjudgmental

Davis and Shah both agree that one of the most crucial elements of music therapy is its ability to help people overcome negative thoughts and self-image, and both therapists actively create affirmative, accepting spaces.

“People come in with a lot of expectations of themselves,” says Davis. “And they come in thinking that this is about performance, or accuracy, or talent. People will say, ‘I’m tone deaf. I can’t carry a tune in a bucket.’ And we have to break through that, because music is genetically programmed into everybody.”

The impact of music therapy

The effect of music on patients in a therapeutic setting has been researched extensively. Over the past 20 years, more than 1,000 studies have been published on the topic, and there is considerable evidence that music therapy is an effective treatment adjunct for a wide range of mental health and addiction treatments.

Music therapy and trauma

There is evidence that music therapy is a useful therapeutic tool for reducing symptoms and improving functioning among individuals with trauma exposure and PTSD.

Music therapy and schizophrenia

Music therapy helps people with schizophrenia improve their mental state, social functioning, and quality of life.

Music therapy and dementia

People with Alzheimer’s disease and dementia saw improved non-verbal expression, reduce anxiety and depression.

Music therapy and addiction

A study of 53 women found that those who experience situational or chronic anxiety related to their addictive disorder saw a significant decrease in anxiety with music therapy.

Music therapy and youth mental health

A meta-analysis of nine papers suggested that for children and teenagers with conditions such as depression and anxiety, music therapy had the potential to improve communication, reduce depression, and increase self-esteem.

Writing a new song

Music can play a critical role in the journey toward recovery by helping people with mental health and addiction issues to safely explore, reconnect with, and regulate powerful and sometimes destructive emotions. By exploring rhythm, melody, sound, and lyrics, they can reconnect with and replenish their inner stores of joy, courage, and creativity on the way to recovering and rediscovering their authentic selves.

Stigma and Addiction

Stigma and Addiction

On the one hand, we see portrayals of addiction popularized through media, entertainment, celebrities, and influencers. It could be argued that these play a role in glamorizing or encouraging it. Societal influence is hard to ignore. Today it’s relatively common to hear how an activity like shopping, working long hours or having a particular fondness for a certain food is being casually described as “addicting.” We also hear people describe themselves as shopaholics, workaholics or even chocoholics. (1) Interestingly, the suffixes “-aholic, -oholic, or holic” are directly derived from the word “alcoholic” and used to indicate “items to which people had become dependent or had an abnormal desire for.” (2)

On the other hand, our society is quite comfortable stigmatizing, condemning, and assigning harsh moral judgment to people experiencing addiction. The stigma is often so debilitating that people hide their situations for fear of being discovered. It delays them from getting the help they need.

This article will explore these terms to reframe an understanding of them and address how using language loaded with stigma and stereotypes is ultimately part of the problem. It will also look at ways to reduce stigma and share resources that can help people who may be living with addiction, and those who care about them, move towards recovery.

What is addiction?

Our understanding of what addiction is has been shifting through continued research. It used to be that there was an almost exclusive association between addiction and substance use. People believed that addiction was a personal choice and that the person couldn’t or didn’t want to bring their addiction under control. Researchers have found that addiction is closer to what they would describe as “compulsive behavior.” (3) In fact, scientists and medical clinicians believe that “addictive activities [help people] escape discomfort – both physical and emotional…to feel good and feel better,” pointing to the “roots of addiction” being associated with “sensation seeking and self-medication.” (4) But even though “addiction is now classified as a disease that affects the brain, not a personal failing or choice,” continued stigma makes living with addiction particularly difficult. (5)

What does addiction do to our bodies?

Addiction interferes with brain function, particularly when our brains desire rewards or experiences that make us feel good. There are many elements to addiction, but neurotransmitters, cravings, and developing tolerance are at the root of addiction.

- Dopamine

You may have heard of dopamine, a neurotransmitter in your brain. It and other neurotransmitters “reinforce your brain’s association between certain things and feelings of pleasure, driving you to seek those things out again in the future.” (6) But, it’s important to note that research shows that they don’t “appear to actually cause feelings of pleasure or euphoria.” (7)

- Cravings

Cravings arise from associations with a substance or behaviour that create euphoria. Dopamine is released and floods your brain. Your brain starts producing less dopamine in response to natural triggers, creating tolerance.

Addiction comes from seeking more of the substance or behavior to “make up for what your brain isn’t releasing.” (8) It translates into a singular focus: trying to feel good again. Other activities no longer give you the enjoyment you once experienced from them. Instead, many things are sacrificed to get there (health, social relationships, jobs, etc.)

Researchers have also determined that there are two main forms of addiction:

- Chemical (where someone can have a mild, moderate, or severe substance-use disorders)

- Behavioural (where compulsive, persistent, and repeated behaviours are observed)

Symptoms may include: (9)

- Intense cravings that affect someone’s ability to think about other things.

- Spending large amounts of time trying to obtain a substance or engaging in a behaviour and much less time on previously enjoyable activities.

- Having trouble with relationships and friendships and avoiding responsibilities at home, at work and in the community.

Feeling irritable or restless and developing anxiety, depression or withdrawal symptoms when trying to stop using a substance or discontinue the behaviour.

Some common addictive substances

Alcohol, opioids, cannabis, nicotine, prescription pain medication, cocaine, and methamphetamine.

Common behavioural addictions

Gambling addiction and Internet gaming disorder (both of which are now recognized forms of addiction) as well as shopping, sex, work, exercise, food, social media.

What is stigma?

Stigma is a harmful misconception that someone forms about a group or person because of the situations that person faces in life. Stigma is dangerous because it “[fuels] fear, anger, and intolerance.” (10) Mental illness, health conditions or disabilities are all situations where attitudes are mainly negative and often cause the stigmatized person to delay seeking treatment.

The stigma around drug use is often based on stereotypes and leads to judgment or discrimination. People can face social stigma, deal with self-perceived stigma and be affected by structural stigma. Regardless of the type, stigma is a contributing risk factor to someone seeking treatment or help for addiction. It reduces a person’s chances of receiving appropriate and adequate care. (11)

Types of stigma

Social

Negativity towards someone living with addiction from their friends or family members, including:

-

-

- Talking about addiction like it’s a choice

- Passing judgment or discrimination using words, labels and images

-

Self-perceived

When someone living with addiction internalizes the negative messages they have received from friends or family. They can develop:

-

-

- Low self-esteem

- Feelings of shame

- A fear of treatment because of the judgment or discrimination they will face

-

Structural

When someone living with addiction experiences negativity, discrimination, a lack of support, or a lower quality of care in:

-

-

- Healthcare and social services settings

- Workplaces

-

How does stigma affect addiction?

When someone living with addiction is stigmatized, it affects them both personally and socially and can weigh on their mental health. In short, stigma makes it more difficult for someone to reach out for help because the act of seeking professional help “appears to carry its own mark of disgrace.” (12) Instead, someone can: (13)

-

-

- Become reluctant to seek treatment.

-

- Develop increased risk of mortality because of delayed treatment.

-

- Feel rejected and isolated. It may seem that people are avoiding them, or in turn, they wish to avoid people.

-

- Experience harassment, violence, and bullying, because of a lack of understanding and empathy.

-

- Face increased socioeconomic burdens as they may have difficulty finding work or housing.

-

- Develop feelings of shame, diminished self-worth, increased self-doubt, and feel that it’s pointless to work towards achieving goals.

-

Ways to reduce stigma:

Language and Stereotypes

One of the most effective ways to reduce stigma involves language. By becoming more aware of how much words matter, stigma can be reduced or eliminated. It removes barriers to help-seeking treatment and changes relationships between someone living with addiction and the other people involved.

Language is powerful. It can create associations and change behaviours. Dissociative language (language that distances or disconnects us from a situation) can be damaging. It creates a misperception that someone who lives with addiction is not in control. We see this when the choice of words tries to provide an excuse for, or legitimize, the situation. For example, talking about obtaining pills “legally” from a doctor may allow someone to attribute blame, deflect responsibility for their involvement, and gain sympathy.

Shifting words and labels

The words we use in conversations about addiction reveal our bias. For example, one way to support destigmatization, is to recognize what scientists and medical professionals have discovered about addiction and shift our mindsets to recognize the situation as a disorder.

Some people with substance use disorders may refer to themselves using negative or stigmatized terms. Please recognize that this may be a personal choice and used within their communities or as part of their recovery.

An excellent resource that can help people gain awareness of language and help to reduce stigma is the Research Recovery Research Institute’s Addictionary®. It states that“if we want addiction destigmatized, we need a language that’s unified.” (15)

You can visit the Addictionary® at: https://www.recoveryanswers.org/addiction-ary/

Avoiding stereotyping

Popular culture and media portrayals help to create misperceptions and feed stigma. There are differing perspectives on controversial advertising and entertainment that expose impulsive behaviours. Some recovery organizations believe they glorify or glamorize addiction, enabling or influencing people’s behaviours. Others believe that these forms of media humanize the difficulties and struggles people can face with both their physical and mental health and while living with addiction.

Depending on the story, other more controversial behaviours and actions are often used to try and establish stereotypically negative character traits. Such portrayals usually start with seemingly docile behaviours, such as vaping and smoking, using props like cigarettes and alcohol to move their narratives forward.

Young people are particularly vulnerable. Many studies show that “attitudes around substance use are influenced very early on by media portrayals…[and] positive associations formed…may be predisposing [them] to early substance use.” (16)

Resources for helping with addiction

Learning more about addiction is a significant first step. Because of its prevalence, many governments and harm reduction service organizations compile and publish excellent resource information on the Internet. Talk to a physician or pharmacist, who will be able to make recommendations for different programs and treatment options for consideration.

Naloxone

Naloxone is a safe, for all ages, fast-acting drug that can help “temporarily reverse the effects of opioid overdoses” when there are life-threatening levels of certain types of opioids (fentanyl, heroin, morphine, codeine) in someone’s system. (17) Naloxone blocks the effects that opioids have in the body for a short time – between 20 and 90 minutes. Administering naloxone can help restore someone’s breathing within 2 to 5 minutes. It is important to note that the “effects of naloxone are likely to wear off before the opioids are gone from the body, which causes breathing to stop again,” so emergency services – 911 – should be called so first responders can intervene. (18) Further, “naloxone has no effect on someone who does not have opioids in their system, and it is not a treatment for opioid use disorder.” (19)

In Canada, take-home naloxone kits are available in two forms: a nasal spray and an injectable. Most pharmacies or local health authorities stock these. They are available without a prescription. In many provinces, these kits are free. It’s a good idea to get a kit and learn how to use it. Keeping one in your car and another at home could make the difference between life or death if someone experiences an overdose. The Health Canada website has videos that show you how to administer each form of Naloxone and links to provincial pages so that you can learn where to obtain a kit. Visit

www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/opioids/naloxone.html

Support Groups and Counselling

Attending support groups or counselling services can help you develop coping skills and share resources to help someone living with addiction.

Being realistic

Remember that taking the first step towards treatment is up to the person living with addiction. You cannot do it for them. Though it might be difficult, try not to let emotions get you. Be kind and check your bias/stigma. Do your best not to show anger or sadness. You also should reserve judgement and refrain from providing unsolicited advice.

Addiction is a complex illness that needs the time and patience of everyone involved.

References:

1. Harvard University (2021 Sep 12).

What is addiction? Harvard Health Blog. Retrieved May 26, 2022 from https://www.health.harvard.edu/blog/what-is-addict…

2. Grammarist (2022).

-aholic, -oholic and -holic. Grammarist. Retrieved May 26, 2022 from https://grammarist.com/suffix/aholic-oholic-and-ho…

3. Raypole, C. (medically reviewed by Legg, T. J. PhD., PsyD) (2020 Feb 27).

Types of Addiction and How They’re Treated. HealthLine. Retrieved May 26, 2022 from https://www.healthline.com/health/types-of-addicti…

4. Harvard University (2021 Sep 12).

What is addiction? Harvard Health Blog. Retrieved May 26, 2022 from https://www.health.harvard.edu/blog/what-is-addict…

5. Raypole, C. (medically reviewed by Legg, T. J. PhD., PsyD) (2020 Feb 27).

Types of Addiction and How They’re Treated. HealthLine. Retrieved May 26, 2022 from https://www.healthline.com/health/types-of-addicti…

6. Ibid.

7. Ibid.

8. Ibid.

9. Ibid.

10. Caddell, J. PsyD. (Medically reviewed by Gans, S. MD) (2022 Feb 15).

What Is Stigma? Verywellmind. Retreived on May 26, 2022, from https://www.verywellmind.com/mental-illness-and-st…

11. Government of Canada. (n.d.)

Stigma around drug use. Government of Canada. Retrieved on May 26, 2022, from https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/op…

12. Vogel, D.L. and Wade, N.G. (2009 Jan).

Stigma and help-seeking. The British Psychological Society. The Psychologist, Vol. 22, pp. 20-23. Retrieved on May 26, 2022 from https://thepsychologist.bps.org.uk/volume-22/editi…

13. Caddell, J. PsyD. (Medically reviewed by Gans, S. MD) (2022 Feb 15).

What Is Stigma? Verywellmind. Retrieved on May 26, 2022 from https://www.verywellmind.com/mental-illness-and-st…

14. National Movement to End Addiction Stigma. (n.d).

Addiction Language Guide. (pp. 5-7) Shatterproof. Retrieved May 26, 2022 from https://www.shatterproof.org/sites/default/files/2…

15. Recovery Research Institute. (n.d.) AddictionaryÒ. Recovery Research Institute. Retrieved May 26, 2022 from

https://www.recoveryanswers.org/addiction-ary/

16. Recovery Research Institute. (n.d.).

It looks cool on TV – media portrayals of substance use. Research section. Retrieved May 26, 2022 from https://www.recoveryanswers.org/research-post/look…

17. Government of Canada. (n.d.).

Naloxone. Government of Canada – Controlled and illegal drugs > Opioids. Retrieves May 26, 2022 from https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/op…

18. Ibid.

19. National Institute on Drug Abuse. (n.d.).

Naloxone Drug Facts. National Institutes of Health. Retrieves on May 26, 2022 from https://nida.nih.gov/publications/drugfacts/naloxo…

Supporting Those with Addiction

Supporting Those with Addiction

One of the often-overlooked challenges with addiction is that the addicted individual is not the only person impacted by the disease. Family and friends may encounter difficulty with the individual’s pattern of behaviour, potentially escalating financial and legal problems, and even just the daily struggle of providing positive reinforcement and support.

It is complicated and typically overwhelming for those impacted when the disease takes hold. Often, family members are unable to observe or note the signs and behaviours that signal addiction. This article offers advice on supporting someone you care about who is struggling with an addiction, no matter where they are in their recovery journey.

What are some indicators to watch for that might reveal addictions?

Often, when the condition is revealed, those close to the person wonder how they could have missed the signs. The fact is, addiction is not clear cut, especially if the addicted person intends to keep it secret or is genuinely unaware that they have a problem. While you should pay attention to all behavioural changes, here are three indicators that you may be able to observe that could help to reveal addictions:

- Absenteeism or avoidance. Have you noticed a decline in attendance or withdrawal from social engagements and/or family events? Within a work setting, you may notice an increased use of sick leave, or variations in arrival and departure times. Additionally, you may notice prolonged breaks or extended absences.

- Excuses. Have you noticed overly elaborate explanations being offered when you check in or reach out to see how the individual is doing or if they missed an event they were expected to attend? This may be particularly difficult to notice given the increased amount of virtual or online engagements due to COVID-19.

- Irresponsibility and recklessness. Has the individual stopped performing specific roles and accountabilities? Are they making careless mistakes or missing key tasks or responsibilities that have significant repercussions?

What is addiction and what are the different types of addictions?