Celebrating Pride Means Supporting 2SLGBTQ+ Mental Health

Celebrating Pride Means Supporting 2SLGBTQ+ Mental Health

June is a time for celebrating the diversity of Canada’s 2SLGBTQ+ communities. But it’s also a time to reflect on how we can nurture and support that diversity every day of the year.

The 2SLGBTQ+ community is disproportionately affected by mental health and addiction issues, and it prevents many of its members from living their best lives and reaching their full potential. For families, friends, and caregivers alike, changing the way we think about 2SLGBTQ mental health and addiction treatment and recovery can transform the outcomes.

Progress and challenges

There is much to celebrate during this year’s Pride Month. As of 2023, Canada is home to one million individuals who identify as 2SLGBTQ+, which represents 4% of the total population aged 15 and older. Three-quarters of Canadians support same-sex marriage, and 61% say they support LGBT people being open about their sexual orientation and gender identity with everyone. Just last year, the federal government unveiled a five-year, $100 million plan to support 2SLGBTQ+ communities across the country.

Yet in some ways, 2SLGBTQ+ visibility and acceptance have never felt more fragile as there is often backlash. Between 2019 and 2021, hate crimes based on sexual orientation rose nearly 60% to reach their highest level in five years.

More than ever, we need to make an effort to understand, celebrate, and make room for queer lives and identities, and that’s especially true when it comes to supporting 2SLGBTQ+ mental health and addiction treatment.

The cost of being queer

The cost of being queer

In a perfect world, people of all genders and sexual orientations would be given equal opportunities to thrive. But the reality is that 2SLGBTQ+ Canadians still face multiple barriers to health, wealth, and wellbeing.

Many 2SLGBTQ+ Canadians live with the trauma caused by secrecy, stigma, discrimination, and fear. In addition to being the target of hate crimes, they are also more likely to experience financial distress, homelessness, and housing insecurity than heterosexual Canadians. Canadians who are 2SLGBTQ+ also have fewer job opportunities and earn significantly less than straight, male counterparts and experience frequent microaggressions at work. A lack of access to medical care, suboptimal healthcare experiences, and poorer health outcomes also diminish quality of life for queer people.

A mental health crisis

In the face of so many challenges, it’s unsurprising that the queer community sees a higher proportion of mental health and addiction issues.

Courtney Sullivan, Addiction and Mental Health Therapist and Support Coordinator at Homewood Health Centre, which is located in Guelph, Ontario and one of the largest mental health and addiction facilities in Canada, provides both outpatient and inpatient treatment for addiction and mental health. They work with clients who identify as queer, including individuals who may be experiencing homelessness, job loss, trauma, addiction, and a range of mental health issues.

“There is a lot of stigma towards the queer community,” they explained. “A lot of people have their families disown them or kick them out or withhold family support. A lot of queer youth, in particular, end up in the shelter system, which exposes them to trauma and substance use, and their mental health can get a lot more complex.”

Research shows that 2SLGBTQIA+ Canadians are seven times more likely to abuse drugs or other substances and five times more likely to have mental health issues. Sexual-minority Canadians are also approximately 25% more likely to contemplate suicide (40% vs. 15% for the general population) or have a mood or anxiety disorder (41% vs. 16%).

Treatment challenges

Not only do 2SLGBTQ+ have a higher likelihood of developing mental health issues and addictions, but their treatment journey is complicated by systemic ignorance and discrimination in the healthcare system.

According to a 2019 survey, 59% of nonbinary people were misgendered daily and only 47% felt comfortable discussing non-binary health concerns with their primary care provider. One in three said their primary healthcare provider had no knowledge about trans/non-binary health needs, and one in four did not have access to in-person spaces specific for non-binary people.

“There’s a large amount of queer people who don’t actually disclose their queerness to their health care providers,” said Sullivan. “The medical system doesn’t have the greatest history,” they continued, pointing out that as recently as the 1970s, homosexuality was classified as a mental disorder.

“People who do disclose to their doctors are often put in a position where they have to educate them about how healthcare should be delivered, which puts a huge burden on the queer community.”

It’s even more complicated for people with an intersectional identity that combines queerness with another identity that puts them at a systemic disadvantage, such as being a person of colour or an Indigenous person.

“Recovery programs and agencies and organizations really need to show their support to the queer community and signal that they are seen, that their experiences are respected, and that the facility is open to work with you,” Sullivan said.

While Sullivan advocates for big changes in the healthcare system, including hiring for diversity and developing organization-wide policies that reflect diverse perspectives, they also believe that small things can make a big difference. As an example, they described a recent situation when they brought a suicidal trans client who didn’t feel healthy at home to the hospital. Asking for help took tremendous courage, but the client was deadnamed three times in a row during the intake process, which almost made them reject treatment. (Deadnaming occurs when someone calls a transgender or non-binary person by the name they used before they transitioned. While deadnaming may be unintentional, it can feel stressful and traumatic because it questions or invalidates a person’s gender identity.)

“The hospital is supposed to be a healthy space, and most healthcare workers are well-intentioned, but systemic homophobia and racism can come out through the policies and the way things work,” they said. “Something as simple as restructuring medical charts so that gender information and preferred pronouns are easily available at a glance can change the experience. Or have care providers identify their pronouns, which is kind of like offering an invitation for that person to give you theirs too.”

S upporting 2SLGBTQ+ mental health

upporting 2SLGBTQ+ mental health

If you are a friend, partner, or family member of a 2SLGBTQ+ person exploring treatment options or actively in treatment or recovery, you can play an integral role in supporting their mental health and resilience.

For Sullivan, these communication tips can help to ensure they feel heard, seen, and supported throughout the journey.

Let them lead. “Your loved one might have a substance use issue, but if they’re not ready to hear it, don’t force it on them,” said Sullivan. “When people get scared, they make threats, like, ‘You need to get sober or else!’ But that ruins the opportunity and the trust.” Instead, let that person decide what they need and set the pace for treatment and recovery.

Keep an open mind. “Come at things with empathy and compassion. Listen to that person. Try to understand why they’re making the choices that they do.” Sullivan pointed out that for some members of the 2SLGBTQ+ community, the use of stimulants is an important part of their lifestyle and sexuality. “It all comes back down to the impact that the person’s substance use has on their life, and what that person identifies as being problematic.”

Respect their experience. “The trauma and the experiences that queer people have are different,” Sullivan explained. “Even if you’re cisgender and you get kicked out of your home, it’s still a different experience than someone being kicked out of their house because of who they are.” Respecting those differences can go a long way toward creating a space for authenticity and healing.

Pride in mental health

Pride in mental health

Pride Month is a time to celebrate the queer community and bring attention to the challenges it continues to face. The elevated risk of mental health and addiction issues is an important part of the story, and one that Homewood Health Centre and other mental health and addiction facilities in Canada are highlighting this year. We all have a role to play in supporting and protecting the mental health of 2SLGBTQ+ individuals, and that role goes beyond raising the rainbow flag.

“We’re having a flag-raising ceremony in honour of Pride here at Homewood, but that’s just the first step,” said Sullivan. “It’s about creating intersectional representation. You want people of colour working in your organization, you want Indigenous perspectives, you want queer perspectives. Be willing to hear the experiences of the people you employ and the people you support. Find out what it is that they’re looking for.”

Learn more about LGBTQ+ mental health.

Learn how to support children who identify as LGBTQ2+.

How to be an Ally

How to be an Ally

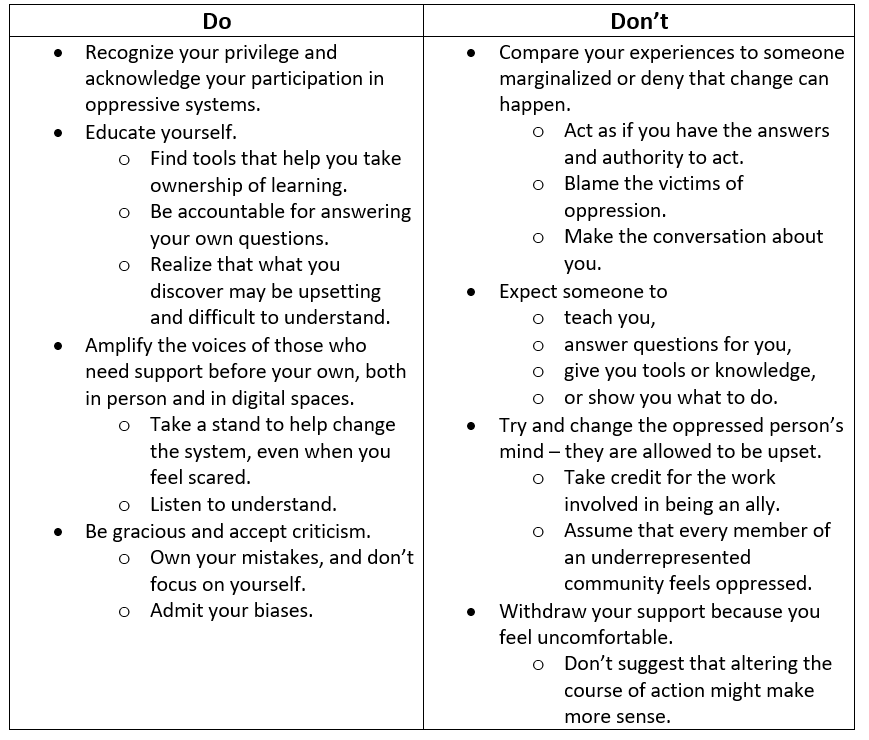

Being an ally is about far more than making a declaration. It’s a conscious, educated decision that leads someone to develop sincerity, focus on introspection, and learn about consistency.

True allies show solidarity for people whose circumstances are different and challenging. There should never be any expectation of recognition or gratitude. An ally must understand this and embrace it. Embracing allyship helps you realize how you live your life and can support earnest changes in behaviours in yourself and society that can contribute to shifts that chip away at injustices and inequities.

In this article, we will explore some of the fundamentals, clarifying what it means to make the personal decision to be an ally and why allies are necessary. We’ll also look at the actions allies can take to strengthen our workplaces and communities.

What is an ally?

An ally is someone who wants to partner with marginalized people in our society to help overturn oppression and inequities that center around topics such as race, cultural identity, gender, religion, sexual orientation, ability, and body type/appearance. Allies focus on standing up “for equal and fair treatment of people different from them” whose voices are underrepresented.[1]

Allies recognize that introducing consistency in their lives can result in solidarity with others because they approach things earnestly, knowing that the right kind of support can change behaviours and ideas. Allyship is most effective when it happens in the context of genuine relationships and everyday interactions.

A large component of being a successful ally is practicing self-awareness and self-accountability.

- An ally must acknowledge how their privilege has benefited them.

- They must be open to listening to understand and learn about the kinds of meaningful actions they can offer as a show of support for people lacking privileged advantages.

Another way to look at it is that an ally cares enough to make a conscious decision to support someone who is a member of a group that the ally is not a part of and who is having a negative experience in their life. They also recognize that allyship is not pity. When enough people decide to be allies, that’s the point where social and societal change begins to happen.

Allyship is only valuable if it’s consistent. It can also be contradictory if the ally enters a situation from a solutions-oriented perspective because they believe they know exactly how to fix a problem. The responsibility for learning about the challenges marginalized groups experience is not something for an ally to expect their marginalized contacts to offer. It’s up to the ally to seek accurate knowledge responsibly. An ally must self-educate consistently and without expecting recognition for their involvement.

Why are allies necessary?

We often adapt what we think, say, and do to blend in with the crowd. It can help us feel accepted, safe, and that we belong, leading us to behave in specific ways, like others in the group, so that we aren’t asked to leave it. Psychologist Robert Cialdini observed that “people copy the actions of others to know how to act in a certain situation. This idea stems from the assumption that if other people are doing something, it must be the correct thing to do.”[2] What’s interesting is that we tend to conform even when we observe or experience something that we know is wrong. The people around us subtly influence us: social actions and opinions are contagious, both good and bad.

Allies dare to reflect and recognize their privilege and use it to “influence inclusion and call out or challenge behaviour [that perpetuates] bias and systematic oppression based on race, gender, sexual orientation and ability.”[3]

What actions can you take to become an ally?

Being an ally comes with great responsibility. Here are some considerations:

How can you be a better ally in the community?

Being present as an ally is about consistency. Show up for all people and groups, observing that each may take a unique approach. An example of a simple action you can take is to acknowledge important holidays and milestones.

Recognize that you might be the one who needs to change or stand up for change to correct a misperception. Pay close attention to language and ideas to reflect that in conversations to show you care. Stand up to discrimination when you see it by modelling active listening. For example, take time to learn the correct pronunciation of people’s names. You could also support someone’s expertise and skills and invite them to share their knowledge within the community.

You also need to respect boundaries. Some people may adapt their behaviours for safety reasons. Don’t chastise them for doing that. Follow their lead and try to understand why they are making that choice. Think about what a shift in behaviour in the future could do that might result in a safer experience for them.

How can you be a better ally at work?

You can start by recognizing that there are inequities in the workplace that affect people’s physical and mental health significantly. These might be centred around income and lifestyle or other factors that affect the identity they portray at work and their ability to be their authentic self.

Known issues include:

- Unequal pay

- Lack of diversity

- Underrepresentation of people in marginalized groups in management/leadership positions

Remote work adds another complication. It’s easy for people to make assumptions about one another when their interactions are virtual. The lack of physical presence can introduce microaggressions that often have remote workers feeling excluded and undervalued.

Allies can help push for changes by actively advocating and participating in these approaches to ensure that concerns are discussed and not diminished.

Create space for productive discussions

Be willing to have and support uncomfortable talks, even if the topics are controversial. It holds the organization accountable for addressing Diversity Equity and Inclusion (DEI) issues, especially if HR policies are already in place.

Develop mentorship opportunities

Supporting allyship can be strategic, allowing people to become “collaborators, accomplices, and co-conspirators who fight injustice and promote equity” through the relationships that develop and actions taken during mentoring.[4] It can be the catalyst to drive change.[5]

Use a strategic and measurement-based approach

Engage in ongoing measurement to evaluate if your DEI policies are effective. This includes creating annual or quarterly plans that outline DEI initiatives that drive or align with the organization’s strategic plans; defining who is accountable for the initiatives, establishing and analyzing key performance metrics to assess the impact of initiatives and programs and incorporating on-going feedback from leaders and employees.

Change the usual ways feedback about DEI issues is collected

Allies can encourage people to share what the organization should start doing, stop doing, and stay doing. Keeping things simple can help everyone feel safe sharing their realities and bringing transparency to what is happening at work. People never want to feel like they are the only ones sharing their situations. There should be zero tolerance for inequity and discrimination.

References:

[1] Wells A. & White B. (2021 February 4) Why is Allyship Important? National Institutes of Health (NIH). Retrieved April 27, 2023 from https://www.edi.nih.gov/blog/communities/why-allyship-important

[2] Cherry, K. (2022 January 20, Updated 2023 March 5). Confirmity: Why Do People Confirm? Explore Psychology. Retrieved April 27, 2023 from https://www.explorepsychology.com/conformity/

[3] Rice, D. (2021 August 18). The Keys to Allyship: Understanding What an Ally Is and the Role They Play in an Inclusive Workplace. Diverity Inc. Powered by FAIR360. Retrieves April 27, 2023 from https://www.fair360.com/the-keys-to-allyship-understanding-what-an-ally-is-and-the-role-they-play-in-an-inclusive-workplace/#:~:text=In%20majority%2Dwhite%20societies%2C%20effective,privilege%20to%20drive%20tangible%20change.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.