The Intersection of Sexual Identity and Mental Health

The Intersection of Sexual Identity and Mental Health

If someone were to ask you who you are, how would you answer that question? We would likely share the things that we instinctually feel form our identity and are essential for us to express. However, we would also likely assess the environment and situation we find ourselves in first to determine the degree of information to share. We gauge other people’s potential interests, determine if we are meeting them for the first time, whether alone or in a group, and collect details about the setting, their appearance, tone of voice, and facial expressions that give us clues. What we say is selective and doesn’t necessarily share every profound aspect of our life experience that has contributed to forming our identities to date at that moment, but rather those that are most important to convey a picture for them to receive and develop quickly to understand.

We can consider all the people, situations, and circumstances that help us determine our identities are like the spokes of a wheel. Ultimately, they converge and intersect at a central point of strength that holds them all in place, the hub. That is our essence, our sense of self: our identity.

In this article, we will look at how intersectionality is an approach to use in many aspects of our lives to develop a greater understanding of sexual identity and mental health, especially in the context of how different points of intersection affect the experiences of marginalized groups within our society. Opening our points of view can help us learn more about ourselves and other people and enhance our understanding so that we can all strive to live well and feel better.

What is intersectionality?

Intersectionality is a way to look at all the different aspects of someone’s life that have influenced them and their experiences. For example, considering where they grew up, where they live now, what their childhood was like, how they were affected by their families and culture, and whether they have had economic advantages that have increased their social standing would all factor into creating both inequalities and power.[1] However, some influences can be even more critical in developing someone’s social standing where “divisions such as gender, ethnicity, class and lifecourse positioning” are likely to shape more people’s lives than others.[2] Researchers have discovered that the social divisions experienced have a more lasting role in influencing a person’s life.[3] Intersectionality as an approach examines how multiple “forms of discrimination…and oppression, like racism, sexism, and ageism might [also] be present and active at the same time in a person’s life.”[4]

The importance of taking an intersectional approach to sexual identity and mental health

Studies are starting to explore how important it is to view intersectional aspects of our identities through a multi-factor lens. Evidence shows how various health conditions are treated socially and by healthcare providers and systems. Overall, there needs to be a focus on reducing the “burden of stigma.”[5]

The intersection of sexual identity and mental health tremendously influences someone’s sense of belonging and identity. But it’s also important to understand that looking at points of intersection should not be limited to comparing only two tangents because it’s the “convergence of multiple systems of oppression that together underlie the ways the ways that individuals interact with the world around them and how they are treated by others.”[6] For those in the LGBTQ2S+ community, where there is a continuum of many sexual identities and genders, in addition to “diverse racial and ethnic groups, differing abilities, and a range of socioeconomic backgrounds” it is vital to acknowledge that divisions and negative connotations present in society make it exceptionally difficult for members to navigate their lives confidently and safely, especially when it comes to obtaining high quality, purposeful healthcare.[7] Negative health outcomes are compounded for LGBTQ2S+ individuals experiencing other forms of discrimination, including racism, colonialism, and ableism. Practitioners may be unaware of how unconsciously managing a case, instead of approaching a situation from a person-centric point of view, can create trauma for someone seeking medical care.

What do we know about mental health in LGBTQ2S+ communities?

Research shows that people in LGBTQ2S+ populations are affected by discrimination, marginalization, and harassment and, therefore, “often experience greater frequency of mental health problems as a result.”[8]

They are:

- more likely to experience depression, anxiety, suicidality, and substance abuse

- at double the risk of developing post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

LGBTQ2S+ Youth:

- experience risk of suicide and substance abuse at levels 14 times higher than their heterosexual peers

- 77% of trans respondents in one survey had seriously considered suicide

- 45% had already tried to end their lives

- trans youth and those who had experienced physical or sexual assault were at greater risk

Statistics also showed that:

- bisexual and trans people are over-represented among low-income Canadians

- trans people reported high levels of violence, harassment and discrimination when seeking stable housing, employment, health, or social services[9]

How does sexual identity interact with other social identities to shape bias?

One of the most significant challenges LGBTQ2S+ communities face is that, historically, the full spectrum of sexual identity has been associated with mental illnesses. The American Psychological Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Illnesses (the DSM-5) is the guidebook many professionals use to diagnose mental health disorders. However, “until 2013, being transgender was still considered a mental illness, and being gay or lesbian was considered a mental illness until 1973.”[10] Biased views and opinions about sexual identity are embedded and endemic in the fabric of the healthcare systems and governments.

The reality that many people face in terms of stigma is that living their authentic identities, which happen to be on a different position from heterosexism in a broad spectrum of sexual identities, often results in them being[11]:

- rejected by their families

- rejected by society

- vulnerable to violent acts

- forced to live with daily microaggressions in their homes and workplaces

- self-critical and experiencing negative emotions such as shame and guilt

- isolated

- chronically stressed

- anxious

Why do LGBTQ2S+ communities experience health disparities?

People whose sexual identity is on the LGBTQ2S+ spectrum face disparities in obtaining unbiased healthcare regularly. These can be related to harassment, where people are subjected to microaggressions, trauma, or violence. They can also face racial discrimination or even rejection from their families and society for what is sometimes perceived as a lifestyle choice. Finally, they can be affected by structural inequalities, including facing barriers to accessing mental health care and receiving a lower quality of care when treated.

Mental health risks for LGBTQ2S+ communities

People experience trauma, sometimes called “minority stress,” when they must repeatedly deal with discrimination and stigmatization to live their lives.[12]

For example, they might:

- Have to “come out of the closet” on multiple occasions, or sometimes daily

- Feel they need to “go back into the closet” to receive some care such as eldercare, long-term residential care, or palliative care

- Have their sexual orientation or gender identity revealed against their will in social settings or to their families

- Need to assess a situation carefully to determine if it is safe to disclose their authentic sexual identity

Minority stress is directly linked to psychological distress and higher suicide risk amongst LGBTQ2S+ communities. It can also contribute to the earlier onset of chronic diseases.[13]

Simply hearing repeatedly about hate crimes, violence, and anti-LGBTQ2S+ legislation can affect health and self-esteem, leading to depression or anxiety.[14]

As a result, people who identify as LGBTQ2S+ have an increased chance of developing more severe substance use and addiction complications because of increased frequency of mental distress, depression, self-harm, eating disorders, suicide, and IV drug use.[15]

How community supports and peer groups can help

People need to feel included in society and their communities, be free from discrimination and violence, and have access to economic resources to help them maintain positive mental health and well-being.[16] However, change and support also come from looking at intersecting factors as part of a more comprehensive approach to mental health treatment. Doing so can “help identify service gaps and prevent or reduce further harm.” [17]

We all have a role in challenging heterosexism, transphobia, and systemic forms of oppression. These are keys to improving mental health outcomes within LGBTQ2S+ communities.

- It can start with developing a better approach to sex education that is age appropriate and includes teaching about sexual diversity, gender identity, sexual health and diseases, and mental health, and addresses intersectionality as part of the standard school curriculum.

- Gay-straight alliance groups help build inclusion and save lives, especially for people who do not have support from families or schools.[18]

- Having safe places to meet, build community and reduce social isolation by supporting healthy connections is essential.[19]

What can people do to improve their mental health?

Improving your mental health can start with small, simple changes:[20]

- Connect with others who can relate to your circumstances, will accept you and provide emotional support

- Unplug from news and social media to reduce stress and fatigue that can lead to feeling hopeless, worried and fearing for personal health and safety

- Prioritize your physical health with good nutrition, restful sleep, and regular exercise. These will also help boost your mood and increase your energy

- Pursue creativity to express your feelings. It can help increase focus, ground you in the present and help you feel proud and accomplished

- Set boundaries so you are not faced with situations that compromise your physical or mental health. You don’t need to respond, and leaving an upsetting situation is okay

- Talk to professionals who can connect you with resources and supports to help you manage your emotions and mental health

Mental health resources for LGBTQ2S+ communities

We’ve compiled some resources that can help. Feel free to explore them while focusing on living well and feeling better.

Canadian

- itgetsbettercanada.org

- The Canadian Centre for Gender + Sexual Diversity | ccgsd-ccdgs.org

- Egale Canada | egale.ca

- Government of Canada: The human rights of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, 2-spirit and intersex persons

U.S.

- The Trevor Project | thetrevorproject.org

- The National Queer & Trans Therapists of Colour Network |nqttcn.com

- Human Rights Campaign: Tools for equality and inclusion. | hrc.org/resources

References:

1. Hopkins, P. (2018). Feminist geographies and intersectionality. Newcastle University. Retrieved March 24, 2023 from https://eprints.ncl.ac.uk/file_store/production/246036/DAEDDA02-4DB2-4B18-9120-7515E81E915F.pdf

2. Yuval-Davis (2011), as cited in Hopkins, P. (2018). Feminist geographies and intersectionality. Newcastle University. Retrieved March 24, 2023 from https://eprints.ncl.ac.uk/file_store/production/246036/DAEDDA02-4DB2-4B18-9120-7515E81E915F.pdf

3. Hopkins, P. (2018). Feminist geographies and intersectionality. Newcastle University. Retrieved March 24, 2023 from https://eprints.ncl.ac.uk/file_store/production/246036/DAEDDA02-4DB2-4B18-9120-7515E81E915F.pdf

4. Hopkins, P. (2018) What is Intersectionality? (00:11-00:22) Vimeo. Retrieved March 24, 2023 from https://vimeo.com/user83638171

5. Turan et al. (2019). Challenges and opportunities in examining and addressing intersectional stigma and health. BMC Medicine. Retrieved March 24, 2023 from https://bmcmedicine.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12916-018-1246-9

6. Yale School of Public Health (2022) Yale LGBTQ Mental Health Initiative: Intersectionality. Yale School of Medicine. Retrieved March 24, 2023 from https://medicine.yale.edu/lgbtqmentalhealth/projects/intersectionality/

7. Ibid.

8. Massie, M. (2020) A Facilitators Guide: Intersectional Approaches to Mental Health Education. UBC Workplace Health Services and Health, Wellbeing and Benefits). Retrieved March 24, 2023 from https://wellbeing.ubc.ca/sites/wellbeing.ubc.ca/files/u9/Facilitator%20Guide%20-%20Intersectionality%20and%20Mental%20Health.pdf

9. CMHA (n.d) Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans & Queer identified People and Mental Health. Canadian Mental Health Association. Retrieved March 24, 2023 from https://ontario.cmha.ca/documents/lesbian-gay-bisexual-trans-queer-identified-people-and-mental-health/

10. Massie, M. (2020) A Facilitators Guide: Intersectional Approaches to Mental Health Education. UBC Workplace Health Services and Health, Wellbeing and Benefits). Retrieved March 24, 2023 from https://wellbeing.ubc.ca/sites/wellbeing.ubc.ca/files/u9/Facilitator%20Guide%20-%20Intersectionality%20and%20Mental%20Health.pdf

11. Ibid.

12. Standing Committee on Health (Bill Casey, Chair) (2019). The Health of LGBTQIA2 Communities in Canada. House of Commons, Parliament of Canada. Retrieved March 24, 2023 from https://www.ourcommons.ca/Content/Committee/421/HESA/Reports/RP10574595/hesarp28/hesarp28-e.pdf

13. Ibid.

14. Collins, D. (2022). 6 Ways to Protect Your Mental Health as an LGBTQ+ Individual. One Medical. Retrieved March 24, 2023 from https://www.onemedical.com/blog/healthy-living/6-ways-protect-your-mental-health-lgbtq-individual/

15. National Institute on Drug Abuse (n.d). Substance Use and SUDs in LGBTQ* Populations. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; National Institutes of Health; National Institute on Drug Abuse; USA.gov. Retrieved on March 24, 2023 from https://nida.nih.gov/research-topics/substance-use-suds-in-lgbtq-populations

16. Ibid.

17. Ibid.

18. Standing Committee on Health (Bill Casey, Chair) (2019). The Health of LGBTQIA2 Communities in Canada. House of Commons, Parliament of Canada. Retrieved March 24, 2023 from https://www.ourcommons.ca/Content/Committee/421/HESA/Reports/RP10574595/hesarp28/hesarp28-e.pdf

19. Ibid.

20. Collins, D. (2022). 6 Ways to Protect Your Mental Health as an LGBTQ+ Individual. One Medical. Retrieved March 24, 2023 from https://www.onemedical.com/blog/healthy-living/6-ways-protect-your-mental-health-lgbtq-individual/

3 Ways Families can Support People in Addiction Recovery

3 Ways Families can Support People in Addiction Recovery

“While most of us have experienced some pain and anguish in our family, that family system can be a source of strength in healing from that pain.”

Dr. Julie Burbidge

Clinical Director, Homewood Ravensview

The negative impacts of addiction on families is well known. Less well known is the positive impact families can have on the addiction recovery journey. Parents, grandparents, spouses, siblings, and even children can play a powerful role in supporting a family member in addiction recovery and beyond.

In this blog post, we look at the difference families can make in the recovery journey and what they can do to support their loved ones as they transition from an inpatient treatment program to daily life.

Family support has a measurable impact

Supportive family dynamics can have a transformative impact. Family support can uplift every aspect of an individual’s life, from emotional wellbeing to physical health to academic and career success.

Even for an issue as complex and uncompromising as addiction, family support can make a measurable difference.

- A study of nearly 1,200 women who underwent inpatient treatment for substance abuse found that those with supportive families were less likely to relapse within six months of their discharge.

- A study of adolescents undergoing substance use treatment found that those who perceived their parents to be highly supportive had better outcomes than those who did not.

- A meta-analysis of 16 research studies found addiction treatments that involve family are associated with a 6% reduction in substance use compared to individual therapies.

- 65% of Canadians in treatment for an addiction said marital, family, or other relationships were the most important factor in initiating recovery.

Supporting a family member on the path to sobriety is no easy task, but the research is clear: family support can make a big difference.

“Positive attitudes and reinforcement from family members can inspire clients’ commitment to recovery,” explained Dr. Julie Burbidge, the Clinical Director at Homewood Ravensview, a private inpatient facility for mental health and addiction recovery in British Columbia. “It can also help them adapt to new challenges or limitations as they reintegrate with the wider world after spending time in treatment.”

Discharge is not the destination

When an individual completes a treatment program, it’s a major milestone and a cause for celebration, but it’s not the end of the road.

After the individual is discharged, the journey continues as they learn to resume their daily lives while remaining sober. The transition can be overwhelming, and it’s a time when family support in addiction recovery may be most needed.

While this transitional period is critical, it can be overlooked and under-resourced, which is why Homewood Clinics developed a series of post-discharge supports for patients and their families. Individuals who complete treatment are invited to participate in 12-month virtual support groups that meet weekly to focus on recovery management. For their families, an optional virtual meeting with a clinician is held each month at Homewood Ravensview. The facility is also launching a self-serve video hub where over 70 minutes of educational content covers a range of topics including talking to children about treatment, setting healthy boundaries, and understanding the stages of change in the journey to recovery. This will replace the virtual monthly meetings, and is meant to allow for more flexibility on when and how families receive these resources.

“Transitions are difficult because they involve uncertainty,” said Dr. Burbidge. “The more time and effort you put into planning for and discussing the transition plan, the more effective it will be.”

How to show your support

Supporting the recovery of an individual with an addiction isn’t easy, even for experts with years of specialized experience and training. For family members who don’t have that advantage, it’s even more intimidating.

Emotional dimensions can create further challenges. Even in families unaffected by addiction, relationships can be complicated. When addiction and mental health issues are added to the mix, the dynamics can be even more volatile.

“Being prepared for the transition home of a family member involves understanding your role in the recovery process,” said Dr. Burbidge. “It also means accepting that family life after treatment will be different and making a commitment to rebuilding relationships.”

Educating yourself ahead of time can help you prepare to provide family support in addiction recovery. Here are three of the most beneficial strategies for showing up in meaningful and constructive ways.

Understand the dynamics of change

People who undergo treatment for addiction are asked to change in profound ways, and that cycle of change doesn’t stop when they are discharged.

“Sometimes family members have the misperception that their loved one will be ‘fixed’ or ‘healed’ when they leave treatment,” Dr. Burbidge explained. “Treatment is an important step in a person’s healing and recovery, but the process continues long after their discharge.”

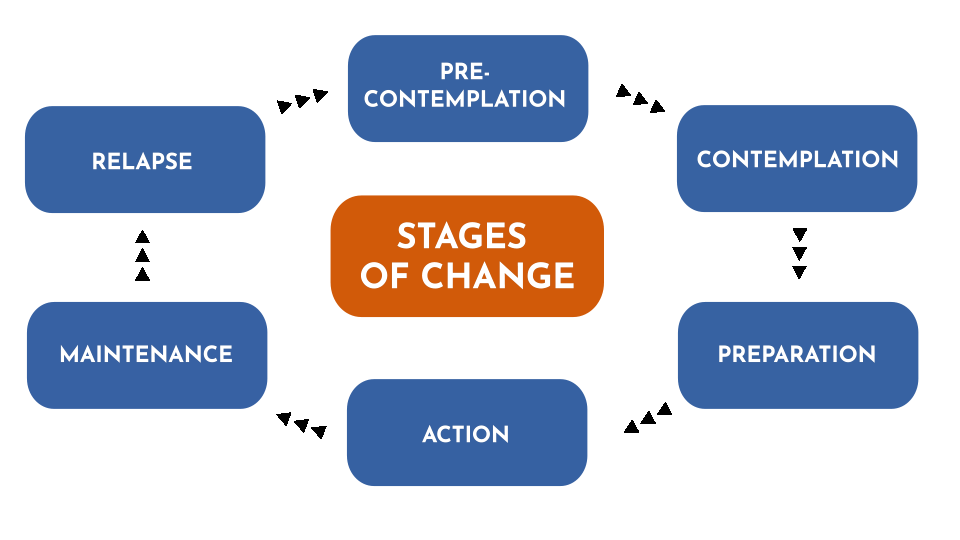

Understanding the stages of change can help family members recognize, accept, and meet people where they are in the journey.

The most important thing to understand about the path to change is that it isn’t tidy and linear. Just as a person with diabetes or asthma can relapse after being released from treatment, a person in addiction recovery may experience a relapse as they work toward sustained change. A relapse shouldn’t be seen as a failure but as one stage among many in the recovery process.

Stages of Change

As people pursue their recovery, they cycle through various stages that can involve new thoughts, attitudes, and behaviours. Every journey is different, and few journeys are perfectly linear. This diagram represents the change model used by Homewood Ravensview, a private inpatient facility for mental health and addiction recovery in British Columbia.

There are several ways you can help to prevent or mitigate the impact of a relapse:

- Talk to the person in recovery about relapse so they know you understand it’s something that might happen.

- Let them know that you are there to support them and ask if they would like you to play a role in their relapse prevention plan.

- Pay attention to your own behaviours. Families can sometimes fall back into old, destructive patterns.

Learn to communicate effectively

Effective communication is the key to healthy interpersonal relationships, but it’s easy to slide into defensiveness and blame during times of stress and anxiety.

Dr. Burbidge advises family members to try using a form of assertive communication called “‘I’ statements” to create a connection with the person they’re speaking to and avoid slipping into harmful communication patterns that rely on accusing, blaming, and shaming. ‘I’ statements focus on your own experience and how you feel about it rather than focusing on what you think the other person is doing wrong.

“This gives us a way to express our feelings in a manner that is respectful and increases the likelihood that the other person will be open to hearing what we have to say,” said Dr. Burbidge.

You can express yourself with ‘I’ statements using a simple formula: “I feel [describe your feeling] when you [describe the person’s actions] because [describe the reason it makes you feel a certain way].

Here’s an example:

| Conventional ‘you’ statement | ‘I’ statement |

|

“You never listen to me. You make me so angry because you just don’t care enough about me to bother to listen when I’m trying to talk.”

|

“I feel angry when you interrupt me because It’s important to me that I’m able to share my ideas with you and feel heard by you.”

|

Set and respect boundaries

During treatment for addiction, people learn how to create boundaries as a way of staying on the path toward healing. As the family member of a person in recovery, you can support them by recognizing and respecting those boundaries. Setting boundaries of your own can also be very helpful in allowing you to preserve your energies and self-respect as you explore new ways of relating to that person.

“Boundaries are a way to establish where you end and other people or external influences begin,” explained Dr. Burbidge. “They are a way of setting healthy limits around what we will and won’t accept or do in our relationships with others.”

To set a healthy boundary with someone:

- Describe the boundary you are setting or the action that is causing you discomfort.

- Express how the situation makes you feel using ‘I’ statements.

- Describe the behavioural change you are looking for in the future.

- Without making threats, describe the action you will take if your boundary is crossed.

Here is an example:

“I feel angry when you interrupt me because It’s important to me that I’m able to share my ideas with you and feel heard by you. Moving forward, I would like it if we could each take turns speaking. This will help us better understand each other and hopefully feel more connected. The next time you interrupt me, I will leave the room and we can continue the conversation later.”

Take the next step together

An individual who has completed an inpatient addiction treatment program has done some hard and courageous work toward furthering their recovery. Re-entering their normal lives post-treatment is the next big step in their journey. By understanding the stages of that journey and learning new ways of communicating and interacting along the way, families can make a positive difference in the individual’s recovery experience and outcomes.

“To truly understand the individual, we have to understand the family system of that individual,” Dr. Burbidge said. “While most of us have experienced some pain and anguish in our family, that family system can be a source of strength in healing from that pain.”

For more insight into supporting a family member in addiction recovery, read these articles from Homewood Ravensview, an addiction treatment program in British Columbia, Canada.

Understanding Family Dynamics: What healthy family traits look like, and how to identify toxic family dynamics.

Supporting Those with Addiction: How to support family members who haven’t reached out for help yet.

Top 5 Tips to Motivate Someone with an Addiction, Towards Treatment

Top 5 Tips to Motivate Someone with an Addiction, Towards Treatment

1. Empathize, don’t criticize. Every time you point a finger, you could be pushing your loved one farther away. Ask questions and listen.There is great power in a supportive loved one communicating with empathy and without judgement.

2. Be firm but fair. Specify some ground rules. Make it clear to them that you will not support their addictive behaviour, and try to set healthy boundaries. With these boundaries in place, they may just be motivated enough to start thinking about quitting.

3. Tell them how you feel. Sometimes, a person living with addiction may not realize how their behaviour has affected you and others in their life. Don’t be afraid to share your feelings with them; doing so could show a significant level of care and support.

4. Use “I” statements. As you express your emotions to your loved one, make sure not to point fingers or fault toward them. They already suffer from their own guilt and shame, so you may risk them shutting down completely. Rather than passing blame and telling them what they did, turn it back around to you. Making statements using “I feel” instead of “you” can help promote healthy communication.

5. Address their fears. A huge factor in resisting treatment is fear of the unknown. Hop onto our site and educate yourself. Knowledge is power when it’s time to have that conversation.

8 Ways to Support a Loved One Living with PTSD

8 Ways to Support a Loved One Living with PTSD

1. Don’t pressure them to talk about their PTSD. It can be challenging for people to talk about their traumatic experiences, triggers, and symptoms.

2. Engage in recreational activities together. Walking, running, board or card games, puzzles, or regular lunch dates with friends and family.

3. Let your loved one take the lead. It’s okay to take the back seat and simply let your loved one know you are on their side, and that you’re here to support them in their time, so they can live the meaningful life they want to lead.

4. Manage your stress. The more calm, relaxed, and present you are, the better you’ll be able to help the person you care about.

5. Be patient. Remember that recovery from PTSD is a process that takes time. It also often involves setbacks. Stay positive and remember that recovery doesn’t occur in a perfectly straight line.

6. Educate yourself about PTSD. The more you know about the symptoms, effects, and treatment options, the better equipped you’ll be to understand what someone you care about is going through.

7. Expect mixed feelings. Supporting a loved one through difficult times can come with a range of mixed emotions. It is okay to get frustrated or feel afraid or uncertain about what is happening to them.

8. Take care of yourself – by continuing to engage in activities that you enjoy, connecting with your own support network and obtaining the services of a therapist or counsellor whose role is to support YOU. This can feel selfish at times, but it is important to remember that we are most helpful to others when we are healthy ourselves. (Source: Homewood Alumni Homeweb)